How revolutionaries defied impossible odds in the Long March and won

China 1934: 130,000 communists retreat from the pursuing KMT forces, marching over 10,000km. Only 10,000 made it to the end. They still won.

If you like this essay, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new essays right in your inbox!

As much as I urge you to read the entire essay, it is a bit longer than usual (30 minutes reading time) and you can safely skip directly to the Long March section by clicking this link.)

China in the 1930s was thrown into seemingly inescapable chaos that had been gripping the vast nation for almost a century. Indeed, it would be impossible to talk about the Long March itself — one miraculous episode of many in the civil war that opposed the Communist Party of China (CPC) against the Kuomintang/Guomindang (KMT) — without talking about the Century of Humiliation.

As we remember the anniversary of the Shanghai Massacre committed by the KMT against the CPC, which directly prompted the Long March, we must also ask: how did the communists win against so many odds? And, what can we learn from their struggle to apply to our own?

In 1839, the First Opium War was triggered by the inability of British merchants to compete with Chinese industry, a tale that undoubtedly has many parallels to the present-day. After all, history is only but a few generations away. British merchants traded silver in great quantities to purchase Chinese tea and silk — back then, the only country in the world that produced these two products. This created a silver crisis in Britain, with stockpiles getting dangerously low, and merchants having nothing to trade for Chinese goods. Ultimately, Britain declared war against China and, with their superior military might at the time against a woefully outdated and outorganized feudal Chinese army, won very unequal trade concessions in the Treaty of Nanking, intended to pave the way for an eventual colonization of China (or rather an eventual imperialization of China from western powers.)

This started the century of humiliation in China under the Qing dynasty. Over time, other wars started chipping away at the already precarious rule of the Manchu, who were outsiders to China (not being historically a part of it), and had to rule with an iron fist. The Second Opium War was waged by a larger coalition so that other traders could secure rights in China, and later Japan itself — which at the time was heavily industrializing and following the western model under the Meiji Restoration — invaded China too in the First Sino-Japanese War, which they also won against the Qing dynasty (the Second Sino-Japanese War being the invasion in 1933 which marked the start of World War 2 in Asia.)

These defeats prompted several movements to modernize China to a more western model, which was seen as the leading bloc in the modern world of the 1800s. These attempts largely failed, and rightfully so as they attacked feudal privileges. For example, the time called for there to be a large standing army, depending entirely on the state and not local lords. But, taking away soldiers from local lords scared them: it made them weaker against the monarchy and took control away from them. Therefore, the attempt was resisted by the same feudal lords who were also at the imperial court. At two different times, the pro-modernization camps were outright massacred by the imperial court to dispose of them, even as the writing was on the wall — by then, the Qing empire had lost three wars without even so much as a fighting chance.

This is our first lesson: reform will be resisted, and so means bigger than reform are required to effect real change.

The modernization period that lasted for the rest of the 19th century polarized China a first time, and led to many open rebellions. The most famous one is probably the Boxer Rebellion (义和团起义, Yìhétuán Qiyi, literally "Movement of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists") that took place in the late 1890s. The rebellion was put down — massacred, even — by a mix of the Qing army and a western coalition, which further fueled tensions down on the ground. Perhaps Mao put it best when he later said ‘a single spark can start a prairie fire’.

In 1912, the Qing dynasty, ruling over 13 million square kilometers, 414 million inhabitants, and 1 million troops, was extinguished.

The most prominent figure of the pro-Republic movement was Sun Yat-Sen, who united all anti-Qing factions in China under a common programme in the Revolutionary League (中国同盟会, zhōngguó tóngméng huì). In 1911, the Wuhan Rebellion broke out. A plot to bomb buildings and trigger a rebellion was discovered by the authorities by pure accident, which forced the revolutionaries to improvise. They launched the rebellion and, to their surprise, succeeded. The rebels proclaimed a Republic in Wuhan and soon enough soldiers from all over the province joined them.

In a way, the Wuhan Rebellion was only a catalyst. The result was owed to an amalgam of failed policies and dwindling imperial power at the Qing court — by then, owing to the decades of failures and losses, something was bound to succeed eventually.

Nevertheless, a plan was formulated by Yuan Shikai, who had switched sides from being pro-Qing to pro-Republic starting in the 1900s. He managed to convince the emperor to abdicate and make Sun Yat-Sen President of the fledgling Republic, with the provision that Sun would step down at that time.

The plan worked exactly as intended and Sun Yat-Sen briefly became President of the Republic when he returned to China in 1911. In February 1912, the emperor abdicated as agreed, and Sun Yat-Sen agreed to step down to let Yuan Shikai take his place — a mistake, as we will see shortly. Our second lesson is that sometimes, to protect gains, some decisions must be made. Sometimes unlawful decisions have to be taken in crisis situations to avoid a mistake being committed. We learn that from the Bolsheviks; the October Revolution after all took place only 6 years later. There, the Provisional Government also wanted the Bolsheviks to step down and share power. At the time, Lenin said no — rightly seeing the danger the Provisional Government, formed of many different factions and coalitions, posed to the gains hard-gained by the revolution. In the span of two generations, Russia went from a feudal absolute monarchy to putting someone in space and back, finding time to defeat the nazis in-between. In Russia, it would have been a mistake to agree to the Provisional Government’s demands and not disband it.

Similar events took place in the Paris Commune, if you’ll allow another aside. In 1871, exploiting a situation in which France could hardly enforce its rule, Paris declared itself independent, ousting the government’s troops (then under Adolphe Thiers) and organizing along the lines of popular democracy and collective ownership of property. However, their fatal mistake was that they stayed in Paris, deciding that their job was done on their end, instead of marching to neighborhing Versailles with their guns and forcibly disbanding the government. Two months later, the French government’s troops had reorganized and came back to Paris, and massacred everyone they found in the streets in what is now called the Bloody Week. Thus the Commune was put down.

A less-than-fatal decision ought to be more viable than an assuredly-fatal mistake, no matter how authoritarian or undemocratic that decision might seem to be.

In China, Yuan’s presidency was supposed to be a temporary one until a Constitution could be established and elections could be held. The KMT won in the National Assembly elections (i.e. parliament), but Yuan saw himself fitting better in the old feudal order than a Republic, and dissolved the assembly. This was the start of his coup. Over the next few years, he purged the KMT from the National Assembly, staffing it with supporters instead, and was named president for life. The newly-established Republic of China was already under threat of being snuffed out. All of this effort would have been for nothing.

Yuan went as far as making imperial robes for himself, clearly intent on reviving the imperial court with himself as an emperor. Even his supporters turned against him and he was forced to flee the course. By pure chance, he died of natural causes on the trip back to his hometown in 1916. This was not a boon, however. His death led to the total breakdown of political authority in China, and gave rise to the warlord era: from 1916 to 1927, there was no effective government over the whole of China.

World War 1 and the May 4th movement

We must briefly make a detour through World War 1 to better set the stage for the transformation of China that subsequently happened, as the May 4th movement was pivotal in the events that will follow. In the war, lasting from 1914 to 1918, millions of Chinese workers left China to find employment in Europe as the population there was being sent to the front, leaving factories empty. Conversely, both Japanese and Chinese goods had trouble finding buyers as much of the world had shifted to a war economy.

At the same time, Japan saw an opportunity to obtain more out of China and perhaps come out of this war being its sole overlord, instead of having to share the treaties with European powers. By then, Japan had modernized economically, and colonized and annexed Korea some years earlier (and bringing with it many massacres that Koreans still remember to this day).

Because Germany owned some port cities in China through mandates obtained in earlier wars and conflicts against the Qing, Japan made the logical move of joining the Triple Entente with France and Britain. They occupied German possessions in the Pacific quite easily. In 1919, peace negotiations took place at Versailles and left China out. China had also technically been part of the Entente, but they were stabbed in the back at Versailles — former German possessions in China were given to Japan instead of back to China.

This was rightly seen as a betrayal in China and, owing to discontent with the Chinese government at the time, sparked demonstrations: while the government was also against the terms of the treaty, they were being blamed for it (and not so wrongfully, seeing as they were the ones representing China in Versailles).

This sparked the May 4th movement, which eventually became the New Culture Movement. On May 4 1919 (hence the name), thousands of students assembled at the historical Tiananmen Square in Beijing and marched towards the foreign quarters, like the Boxers had done only two decades earlier. They were stopped by police there, and decided to go to the home of the Foreign Minister. They burned it down, and from there the police broke up the protest.

Eventually, the government agreed not to ratify the Treaty of Versailles.

In conjunction with this event, the October Revolution was taking place at the same time. Word of it reached China by 1918, and made huge waves there. For one, the Tsarist system was perhaps the closest living form of government to the Qing dynasty. When the Bolsheviks took power and denounced the duplicity of the western powers, this message resonated with the Chinese who had just received the brunt end of it in the Treaty of Versailles: for all their talk of democracy, freedom, and individuality, it was clear that they believed very little of it seeing as China, who had materially supported the Entente in the war, was left out of any talks about their own territory.

The Communist Party

In 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) was founded in Shanghai, back then the most developed city in the country. Marxist study groups had existed in China for several years — and we’ve talked about study groups when it came to studying Vietnam too, as part of a strategy to eventually establish a party. This is a universal lesson: the struggle begins with agitation and education, much like a flower doesn’t blossom into a beautiful rose without first sprouting a seedling.

The nascent Soviet Union sent advisors to the CPC, who suggested forming a united front with the popular KMT, still under Sun Yat-Sen’s leadership (until his death in 1925). They negotiated an alliance, and, under it, members of the CPC could also join and participate in the KMT. Sun Yat-Sen himself, despite not being a communist, reorganized the KMT at this time along the disciplined lines of the Bolsheviks, making it a much more effective political organization — remember that the KMT did not rule China, the country was broken up by warlords who carved pieces out for themselves. The internationally recognized authority in China was the short-lived Beiyang government.

This affinity for the Bolshevik organizational tactics made the alliance more easily achievable, despite the KMT resolutely not being communist in any way. Working with the CPC (who was still very small at the time) was beneficial for them however, as communist organizers did diligent work and brought many members to the ranks of the KMT. The CPC, for itself, gained experience and some members through this arrangement. This is another lesson: sometimes, we may have to work with groups we are at odds with. The point to do so is - does this bring us closer to our goal?

This marked the First United Front. But, when Sun Yat-Sen died in 1925, Chiang Kai-Shek (蒋介石, Jiang Jieshi) replaced him by using his connections at the Guanzhou military academy.

He came from a military background and had been sent to Russia by Sun Yat-Sen to study the October Revolution, the Red Army and the USSR’s system of governance. Despite this, he remained a staunch anti-communist and had never accepted the United Front.

Just one year after his ascendance as leader of the KMT, Chiang Kai-Shek undertook the Northern Expedition, which aimed to remove the warlords in southern China and put it under KMT control. This succeeded, but, as the KMT emerged stronger than before and Chiang found himself reaching Shanghai, he took a decision that cost him dearly decades later.

As the CPC members in Shanghai saw the KMT army approaching, they decided to stage an uprising in the city, counting on the KMT to help them. Instead, he parked his army outside the city, letting the events unfold. This was the Shanghai Massacre. All in all, over 5000 people died.

The CPC found itself in an existentially threatening position. Shanghai was their base, the most industralized city in the country, where they could organize wage-workers. Soon, the CPC was driven out of all urban areas by the KMT and an open war was declared on them — Chiang notably had a particular fixation on the CPC, even going as far as preferring to fight against them rather than the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese war.

This is where Mao Zedong makes his appearance. Up until then, he had been the leader of the Peasant Bureau in the KMT, spending time in the countryside in a minor office. The Bureau was tasked with reaching out to China’s rural population and addressing issues such as land distribution and agrarian reforms, much like had happened years later in Vietnam.

But, it was during that time that Mao realized the revolutionary potential of the peasantry — historically in China, most revolutions against previous dynasties had also heavily depended on the peasantry as a military force, owing to China’s feudal economy. There, he announced to his comrades in the CPC that they could either try to steer the peasant revolution in a productive way, or they should get out of its way before it sweeps everything away.

After the initial driving out of urban centers, the Soviet advisors called for communists in China to launch uprisings everywhere they could, with disastrous results. Mao was called to lead one such uprising in central China, and his forces were forced to flee to the mountains of Jiangxi Province.

The exile in Jiangxi lasted for several years, under constant harassment by KMT forces in skirmishes. It was there that Mao emerged as a much bigger leader than he had previously been. He worked on the rural base area model while there, and in the early 1930s, along with Zhu De and Zhou Enlai (two very important figures in the civil war), worked with millions of peasants in Jiangxi to answer their needs — in terms of land reforms, family structure (to give just one example, in feudal China women only received a personal name, which was only known to the family and no one else), and other proposals in peasant society. This created a base of support in Jiangxi along the peasantry, who saw for themselves what the communists could do for them and their needs. Notably, landlords in China were not quite the same as what we think of today — they extracted rent for the usage of (agricultural) land, but were more like feudal lords, with power over their ‘tenants’. Admittedly, this did not make them very popular with the peasantry, especially after they had experienced land reforms for themselves.

The Long March

In 1933, Japan invaded China, marking the start of World War 2 in Asia, years before the European fronts opened. Yet, Chiang Kai-Shek was more concerned about stamping out the communist factions once and for all over facing the invasion.

The base area at Jiangxi became the focal point of his military efforts, and he began a series of encirclement campaigns there, aiming to block the base area with troops and slowly closing the ring around the CPC troops. The first of these campaigns was defeated by the communists who drove off the KMT forces. Chiang kept the pressure up, and even received military advice from the Nazi party who had come to power in 1933. By 1934, finally, it became apparent that the last encirclement effort was going to be successful. Thus, a difficult decision had to be made: to save even some troops, some would have to be left behind. But to do anything else would mean death for everyone.

It must not have been an easy choice by any means, and no one should ever have to find themselves in such a situation. But, when one is knee-deep in it, they have no choice but to find a way out.

The plan was thus made to try and reach another Red Army battalion and join up with them to regroup their forces. They had no clear idea as to how they would achieve this, but it was either this or awaiting certain death.

They had no vehicles or planes. They had only the weapons on their backs and their own two feet.

For over a year, the CPC forces — then known as the Chinese Red Army (and later becoming the People’s Liberation Army) marched over 10,000 kilometers (6200 miles) while being pursued by KMT forces.

What they did during that time is nothing short of a miracle — or, perhaps, the unbounded limits of human intelligence and creativity.

The direct path between Jiangxi and Yun’an is ‘only’ 1400 kilometers long. But, because they were pursued by the Nationalist forces, the Red Army forces could not simply take the direct route. Though we will get into the details, this map alone does not capture the extent of the hardships faced on the march. Western China, which the forces had to go through to reach Yan’an, has some of the most difficult terrain in all of China.

The withdrawal took place on October 16, 1934. It was not going to be easy — in an encirclment situation, the defenders are cut off from any supplies, be it food, troops or weapons, and the attacker side can slowly but surely reinforce their own capabilities freely. On that day, a force of more than 130,000 soldiers and favorable civilians attacked a line of KMT positions, of which more than 86,000 actually broke through and escaped beyond. The remainder, mainly wounded and ill soldiers, stayed behind to stop the KMT forces from pursuing the marching Red Army forces, diverting them into their own skirmish.

Zhou Enlai had been made aware of a local warlord who preferred not to waste his manpower in this civil war, and he sent someone to negotiate safe passage through his lines. This sounds straight out of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but it happened less than a century ago. Remember that at the time, China had just shed its imperial millenia and was still, in the chaos, operating much like the imperial court had been.

The Red Army crossed Xinfeng River — the one near Meizhou on the map above, just below the red positions at Jiangxi — and marched into Hunan province, but KMT fortifications had been erected at Xiang river and another major battle ensued. Out of the estimated 86,000-100,000 Red Army soldiers who left Jiangxi, it is estimated that only 36,000 were left after this encounter (including losses during the initial breaching of the encirclment).

But remember how this story ends: the Chinese Red Army won. And not only this battle, not only the Long March, but they won over the entire KMT and now govern China.

The initial plan had been to join with He Long’s army in Hunan, but this became too risky with KMT forces in hot pursuit — and in large numbers. A meeting of party cadres was convened in Tongdao by Zhou Enlai to discuss the next steps. At this time, the Red Army forces had marched over 1000 kilometers (600 miles) in just a few short months. It was now December.

There, Mao Zedong proposed that their forces move to western Guizhou Province, and try to establish a base area there, where KMT defenses would be weaker. On the map above, this was shortly after Guilin. To do this, they would travel to Zunyi — which is visible on the map.

The plan was debated by Bo Gu and German communist Otto Braun (who was serving as an advisor); they felt they did not need to take a detour but could simply march into the eastern side of Guizhou. Mao held his ground: that would be exactly what the KMT expects; which means that the western region of the province will be much weaker. Mao’s arguments won and the army marched for Zunyi, taking it swiftly as expected.

The Zunyi Conference was held in the city from January 15 to 17, 1935, and a reshuffling of the politburo emerged. At this time, the escaping Red Army forces in question were in a precarious position: they were weakened from engagements with the KMT, some of the troops were demoralized, and they had no clear plan after their first had become too precarious. But, because they had changed their direction suddenly and for seemingly no reason, they had been afforded some time before KMT forces could catch up with them.

Prior to the conference, Bo Gu and Otto Braun were the two figures which Zhou entrusted with the strategic planning. However, they were harshly criticized for their failures during the escape. Bo Gu attributed these losses to the enemy’s numerical superiority and poor coordination from their own forces.

This reasoning was rejected, and for good reason. There was plenty to criticize during the initial breaching and subsequent crossing of Xiang river: the retreat had been carried out shoddily and in disarray (it is famously said that Zhou only alerted commanders of who would remain and who would leave with just a few hours notice). Soldiers took with them whatever they could carry, not what was necessary to carry: they took with them printing and ammunition manufacturing equipment among other cumbersome gear. The entire force of 80,000 had to travel along mountain trails so narrow they could only clear a single one in one night. Meanwhile, Chiang Kai Shek had deployed 77 regiments from 16 divisions to pursue this contingent. While the Red Army forces managed to breach through the five encirclement lines around Jiangxi, they had suffered heavy losses through it, and this was considered unacceptable. At Xiang, the retreat was delayed by the heavy equipment the troops carried, and a pincer attack was mounted by the KMT along with air support. While some troops were being ferried across the river, others yet waiting for their turn sacrificed themselves so their comrades could cross safely against the KMT offensive.

Even before reaching Zunyi, all odds had been placed against the Red Army. If any chance of success was to be unearthed, it would require a fundamentally new approach to the entire battalion. And for that, a struggle session — a session in which people are encouraged to bring up objective criticism, not of the person but of their results — was needed. Thinking precedes action, and action informs further thinking.

Whereas Bo Gu defended his actions by citing objective problems — the sheer numerical forces of the enemy and the experience of the troops under their command, Mao attacked actionable errors: the purely defensive action undertaken during the counter-campaign (the one that broke through the encirclement), and the way the march had been organized afterwards [unfortunately, my source doesn’t detail this point more and leaves it at that.]

This is another lesson. You can’t really do anything against superior enemy numbers: they will be there regardless of whatever you do. Therefore, saying “the enemy is bigger in numbers” is certainly an objective reality, but it is also not actionable; no productive strategy can come out of this. Where you can effect change however is in how you react to this numerical superiority. And, the enemy being present in superior numbers will ultimately change how you react to it versus how you would if they were in an inferior position.

It is noted that Zhou Enlai also criticized himself at the conference, blaming the Red Army’s failures on poor decisions at the leadership level, of which he was ultimately responsible for, being the general of the army.

The Politburo (political bureau) agreed with Mao’s arguments, and elected him to its Standing Committe. Zhang Wentian, another influential figure, was then assigned to draft a resolution evaluating the Fifth Counter-campaign, the official name given to the Long March. Even in hot pursuit and in unspeakable odds, administration must go on. We must be able to learn from our mistakes on the spot, and not only that, but efficiently communicate them to an entire contingent of several thousand troops.

Another conclusion of the Conference was to give Bo Gu’s responsibilities over to Zhang Wentian, and setting up a group of three — Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Zhang himself — to take command of all Red Army operations. In common historiography, this event is often called a part of “Mao’s rise to power” as if he was a warlord or fashioned himself an emperor. But ask yourself throughout this entire essay: what would you have done differently? Clearly, Bo Gu’s strategy had led to some costly outcomes, and clearly there could have been at least even attempts to avoid these mistakes.

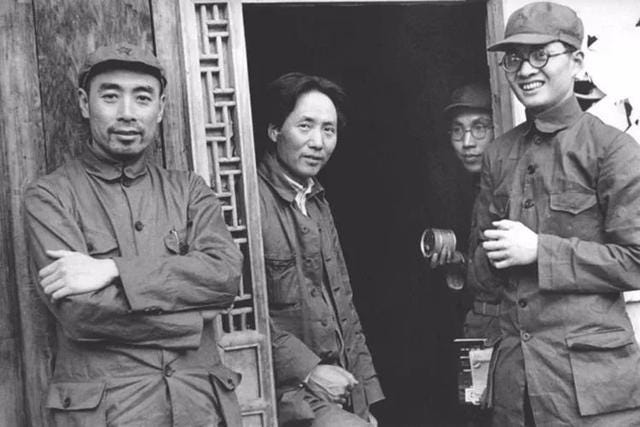

To learn, we must struggle with the facts: we confirm and infirm them and in doing so, there emerges a resolution. We do not learn from osmosis, from simply being in close proximity to facts. Bo Gu was not chastised for making the mistakes per se, rather, he was held away from leadership positions when it became clear he was not the most suited for it (and as seen in a photo earlier, he featured with Zhou and Mao at Yan’nan in 1935). Bo Gu would end up dying a martyr during the war against Japan.

Instead, it was during the Zunyi conference that Mao emerged as a capable general and leader of armies, a trait he would keep for the entirety of the civil war.

Under Mao’s leadership, the Red Army changed tactics and confounded the KMT forces. At Chishui river, for example (portrayed on the map by the circling around back to Zunyi), the Red Army forces confused the enemy out by crossing the river four times, for no reason other than to tire him out and leave him in disarray. Years later, taking from his experiences during the Long March and in the war against the KMT and Japanese Army, Mao wrote On Guerilla Warfare, which I urge everyone to read (link here.)

These new tactics, focusing on swift maneuvers, managed to outmatch the otherwise superior — but rigid — KMT divisions.

Over several months, the reorganized Red Army evaded, confounded and harassed the KMT forces near Zunyi, slowly making their way to westward Yunnan province — Chiang Kai Shek, fearing the new Red Army, had moved his troops away from Yunnan to reinforce Guizhou. In writing these lines, I am reminded of an old precept from a little-known Chinese book, the 36 Stratagems: Besiege Wei to Rescue Zhao.

An attack was feigned on Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, which was lightly defended. In response, Chiang Kai Shek hurriedly called reinforcements to Kunming. When he did, the Red Army suddenly moved straight north — which can be easily seen on the map (the westernmost path). Kunming had never been the actual target.

There is a very vital, if perhaps obvious, lesson here: the enemy may seem daunting, but he too has constraints. He only has so many troops — not an infinity of them. He only has so many commanders. He only has so many weapons. To force him to move reinforcements from one area to another means that he will leave somewhere less defended, and means that these troops have to physically get from point A to point B; they don’t just teleport. To take a barracks from him means he will have that many less weapons to fight with — at least in the short term. All of these operations can be exploited for one’s own goals.

Moving north, the army crossed the Jinsha river, an offshot of the famous Yangtze river. This was the sort of terrain the Red Army was faced with throughout the march through Yannan: valley rivers carved over millennia into deep and steep ravines.

With the crossing complete, victory seemed within grasp. But the tribulations were not over. From there, the Red Army had to cross mountainous peak terrain, at heights of up to 4000 meters above sea level (2.7 miles), facing shortages of food, rough climatic conditions, and above all, hostile ethnic minorities. To guarantee safe passage and in accordance with the CPC’s policy on nationalities within China, Chief of Staff Liu Bocheng was sent to make contact with the Yi minority in Dalian Mountains. The Guji tribe leader agreed, and persuaded the other tribes to remain neutral in the fight. The Red Army was thus able to reach the ferry on the south bank of the Dadu river.

When the army got to Dadu, they realized that the crossing was tortuous and would take too long. In some accounts, it is said that they found only four boats there, which meant crossing would take the entire army months. Instead, the leadership decided that they would race to Luding bridge some 170km upstream, as the KMT had not yet had time to destroy it. If they could beat the pursuing forces there, they might have a chance to take it. To do so, the Red Army covered the distance in two days — marching 85 kilometers each day (52 miles).

The battle has been immortalized in the painting that opens this essay. In an effort to prevent the Red Army from crossing, the defending KMT forces had removed the planks normally laid across the cables. There was very little bridge to speak of by then. Below, some 15 meters under (50 feet), the roaring waters of the Dadu river, churned into fury by the melting spring snow that gorged its stream, were sure to swallow anyone who lost their footing — or rather their grip on the precarious cables that remained of the bridge.

And on the other side, KMT troops waited in their machine gun nests. 26 volunteers formed a shock commando, with the sole goal of wiping out the force on the other side of the bridge so the rest of the Red Army could cross. They were exhausted after months of marching and running battles. Still, slowly, they crept across the bridge with their weapons in one hand, and the chain-link cable — their only lifeline — in the other. Quickly, artillery shells started pounding down on them, most of them landing in the river, launching jets of water up to the advancing commando. Four of the 26 fell to their deaths. Machine gun fire was spraying the bridge but, with little visibility and with how much the bridge must have been swaying, they reportedly failed to hit anyone.

The remaining 22 soldiers crossed the bridge. The most difficult part was behind them. The KMT forces stationed there amounted to a small squad (somewhere between 10 to 20 soldiers) under the orders of a local warlord allied with Chiang Kai Shek, and were quickly overwhelmed.

Having crossed Luding Bridge before the remainder of the KMT forces even reached it assured victory more and more for the Red Army. They quickly made a trek down the mountain from there, some 35 kilometers down. It is said that during the trek down, the oxygen was so thin at altitude that some of the men who sat down to rest never got up again.

By June 12, 1935, the First Army — the one we have been following so far — made contact with the Fourth and moved north together at Lianghekou (a little northeast of Maogong on the map above). With this, their numbers replenished to over 100,000. On the second day, the Central Committee called for another meeting to reassess the situation. The chief problem the two armies were confronted with was where to establish a new base area; in a report, Zhou suggested that:

The new base area must cover a wide area and allow for highly mobile operations.

It should have a large population and a fairly sound mass base (non-members or non-activists that still support the party).

It should have good economic conditions.

The unanimous conclusion was to establish a base at the border between Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces. Another problem emerged, however. The Fourth Army had over 80,000 men under its command compared to the remaining 30,000 in the First Red Army under Mao. As such, Zhang Guotao, commander of the Fourth Army, was able to commandeer leadership of operations from that point on. At the conference, he agreed to move north with everyone else, but afterwards raised all manners of objections about it, and making secret plans to move south instead. He was being duplicitous and could put the entire front in jeopardy with his selfishness.

And the Long March was still not over.

The united armies were divided into two columns; they would separate along different paths and meet up again at the Xiahe River. The right column began to cross the wild and untamed grasslands in northern Sichuan, full of weedy swamps and black sludge pits. The weather changed unpredictably; in a moment, clear skies could give way to fierce winds rushing in from all directions at once, accompanied by torrential rains. The boggy quagmires would swallow anyone who made the slightest miscalculation when stepping in them. The soldiers had to trek over long distances with little food, and the cold and hunger sapped their strength. Many died on these grasslands.

Nevertheless, after marching six days and nights, the right column emerged at the designated location and waited for the left column. However, it was there that Zhang Guotao, giving all kinds of pretexts, refused to march north and instead wanted the column to abandon post and march south. Zhang attempted to split the Central Committee and sent a telegram without their knowledge to the political commissar, giving him the order to march south. Ye Jiangyin saw the telegram and immediately reported it to Mao Zedong. The leaders of the First Army thus held urgent discussions, and decided that they would set out north this very night, undercutting Zhang’s plans as much as possible, in accordance with the strategic principle of unity of action — that is, if one is not happy with a decision that was democratically approved, they can certainly criticize it, but they must nonetheless carry it out. This is a very effective strategy when building a movement.

The northbound contingent reached the Lazikou Pass (end of the arrow starting at Luding on the map above), a narrow pass with tall, vertical cliffs. Scaling the cliffs, a vanguard of the Red Army forces made a surprise attack on the rear of the defending KMT troops, breaking through to southern Gansu in one offensive. Immediately after that, they occupied the town of Hadapu. They learned while in Hadapu that there was a very large Soviet base area in northern Shaanxi along with a large contingent of troops (at the time, the CPC was still organizing under the Bolshevik model, hence why they were called Soviet base areas — these were not Russian bases).

By then, it was mid-September 1935. Things were suddenly moving very fast after the Army had broken through the KMT encroachment in January.

A meeting was held, and the politburo decided to press on to northern Shaanxi, which they reached on October 19 of that year. The Long March had covered over 12,500 kilometers, crossed eleven provinces, and saw more than 100,000 of their comrades die on the way. But it came to an end on that day.

The politburo, which I’ve mentioned a few times, was concerned with the political leadership of the party, and therefore the First Army was ultimately operating under the CPC. This structure is too long to get into at this time, but a lesson we can take from it is that even in situations of war, there needs to be other leadership. One success of the Red Army during this trek was in appointing the right people (skilled people) in the right positions. But to do so, they needed a structure to make sure the right decision was taken and would stick. Even in a situation as desperate as the one they were in, administration beyond pure military campaigning was required to sustain the effort.

After the March

We know the rest of the story, of course. The war against the KMT paused with a Second United Front in 1936. It was actually negotiated illegally on the KMT side; Zhang Xueliang was the military leader in Shanxi for the KMT, and his father had been assassinated by the Japanese in 1928. He opted to place Chiang Kai Shek under house arrest during a visit and then invited CPC representatives, including Zhou Enlai. An agreement was reached to form a second United Front, and Zhang was placed under house arrest in turn — anecdotally, when the KMT fled to Taiwan Province, they took him with them, and he continued serving his sentence until the 1990s in Taiwan.

Mao continued to lead troops against the Japanese after showing his capabilities during the Long March. He continued advocating for guerilla tactics, especially as in China and elsewhere (we’ve mentioned Japanese tactics in Vietnam before), the Imperial Japanese Army often controlled urban centers, but could leave nothing but very little defense in the countryside — protecting infrastructure mostly.

After Japan surrendered in 1945, hostilities between the KMT and the CPC picked back up. When surrender seemed imminent in 1944, Chiang Kai Shek stopped making offensives and instead bode his time to resume the fight against the CPC, using the lend-lease program from the U.S. to build a stockpile of weapons. As for the CPC, they had been a major opponent to the Japanese army during the war, and had won the hearts of the Chinese people in the countryside due to their resistance efforts — not just carrying it out, but organizing resistance as well in localities. It is very safe to say that the CPC came out of the war more popular than the ruling KMT had, as people rightly saw the KMT as being unconcerned with the invasion that led to massacres such as the Rape of Nanjing. By 1947, the Chinese Red Army had reorganized as the People’s Liberation Army and were the ones that liberated Nanjing.

A coalition government was negotiated after Japan’s surrender but had always been doomed to fail. Full-scale fighting broke out again between the two sides. The KMT drove the communists away from their long-standing base at Yan’nan (since the end of the Long March), but that proved to be a fairly meaningless move as the CPC had already relocated most of their support base in Manchuria and North China.

In 1948, a battle took place at the Huai river, involving more than a million soldiers combined. The CPC won the battle, under Mao Zedong’s strategic vision (his account of the battle can be freely read here), and the KMT was routed. In 1949, the remaining nationalist forces had been pushed to the eastern coast, and the disorganized remains fled to Taiwan, abandoning the mainland entirely. The only reason the CPC could not pursue them at the time was because the United States stationed ships in the Taiwan Strait to dissuade them, and the PLA didn’t have a sufficient navy to take them on at the time.

That same year on October 1st, the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed.

Thank you for reading.

Great read!

The Long March is mythology, however.