How Vietnam decolonized and what we can learn from their struggle

From forming a liberation struggle up to forcing the colonizers to surrender

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

The references used to write this essay come mostly from auto-translated Vietnamese sources, hence why they do not appear in the body.

In 1922, a young Vietnamese man working for Le Paria in France wrote the following in a short press dispatch:

An old Annamese woman, also a salt carrier, had an argument with a woman overseer regarding the stoppage of part of her wages. On hearing the overseer’s complaint, the officer, without more ado, took it upon himself to give the carrier two stinging slaps in the face. While the poor woman was stooping to pick up her hat, the civilizer, not satisfied with the slaps he had just given her, furiously kicked her in the lower abdomen, immediately provoking a great flow of blood.

When the unfortunate Annamese fell to the ground M. Sarraut’s collaborator, instead of succouring her, called for the village mayor to carry her away. This worthy refused. Then the officer called in the victim’s husband, who was blind, and ordered him to take his wife away. The poor old woman is now in hospital.[source]

Thus over a hundred years later, a written record exists of how the ‘civilizing’ French treated their colonial subjects in Vietnam and elsewhere.

But that man’s legacy would not end at simply writing about news in the 1920s. This man’s name was Nguyễn Sinh Cung, though you might know him better as Ho Chi Minh.

In 1922, Vietnam — and the whole of Southeast Asia, then called Indochina by the French (being at the intersection between India and China) — had been colonized and under French rule for over 64 years. At the tail end of the European colonization period, Vietnam provided the capacity to grow and extract — what else — precious crops and minerals such as tea, rice, coffee, coal, zinc and tin (rubber would not become precious until the two World Wars). Through the most abject exploitation of the indigenous population, France would guarantee not only access to these resources but also their production in great numbers. Finally, through the colony, the French were able to forcefully open markets for their business interests, who happily invested capital into, and received dividends, from the most violent exploitation of Vietnamese workers. The more a colonial subject gave of their health to make “French” rubber, the higher the return the French businessman made on bonds, stocks and other instruments of finance.

Thus came situations like Ho Chi Minh described, where torture became commonplace for the most basic transgressions, and were not only overlooked, but even rewarded. In the same news brief, he opened with the following event:

Under the title ‘Colonial Bandits’ our comrade Victor Meric has told us of the incredible cruelty of a French administrator in the colonies who poured molten rubber into the genitals of an unfortunate Negress. After which, he made her carry a huge stone on her head in the blazing sun, until she died. This sadistic official is now continuing his exploits in another district, still with the same rank.

The colonization of Vietnam was not made easily, a testament to the resolve of the Vietnamese people — or perhaps to French ineptitude. If you subjugate a people, then they will inevitably fight back against this subjugation. No amount of torture, massacres, laws and decrees can change that basic fact. Thus the colonization of Vietnam was made in fire: in 1858, a joint French and Spanish force (because neither could take over the entire country by themselves) attacked the port of Da Nang with 3000 troops. After managing to capture the city, the French forces tried to advance inland but found themselves facing strong resistance and remained locked in the city for several months. Again with Spanish help, the French attacked Saigon instead (now Ho Chi Minh City) in the South to open up a second front and ease the pressure on their troops in Da Nang. Despite this new development however, resistance was still intact and made advances to the widespread rural countryside almost impossible. It took the arrival of 3500 additional troops to break the stalemate that had set in by 1861.

Finally, in 1864, the emperor was forced to negotiate with France to put a stop to the invasion. The Treaty of Saigon ceded three southern provinces to France, and opened three ports to international “free” trade, permitted missionary activity across Vietnam, and required Vietnam to pay a large debt to France. Missionary activity served a specific interest to colonizers: they provided a casus belli for war if they were ever to be turned away, they provided social services to deepen the reliance on the colonizer (such as hospitals, alms for the poor, etc.) and they also set up enterprises of their own. In Vietnam, Catholic missions — who all belonged to the Missions Etrangères de Paris, a large-scale network founded in 1658 that still exists to this day (they even have a website), owned agricultural enterprises of their own, i.e. plantations.

The treaty “only” created what was called Cochinchina, i.e. a colonial holding in the southern part of Vietnam. Over the next twenty years, and with more political maneuvering and military assaults, France consolidated its rule over the entirety of Vietnam. In a first stage, they divided Vietnam into three regions: Cochinchina in the south, which we already mentioned, Annam in the center, and tonkin in the north. Immediately after, the French created a centralized colonial administration that replaced the traditional feudal structure. Of course, the colonial economy followed. Infrastructure such as railroads and ports were built to benefit the extraction of natural resources back to France. Trade policies were forced onto Vietnam, forcing the protectorates in the north to rely on French goods instead of importing perhaps cheaper or higher-quality goods. French education was made mandatory, but only to create a small class of loyal compradors [class of colonized who serve the interests of the colonizer]. Ultimately, colonialism is a system.

In 1887, France consolidated all of southeast Asia (and the two Vietnamese protectorates) in what it called the Indochinese Union, which incorporated Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Pockets of resistance and rebellion would persist throughout the 1890s, but would ultimately all be defeated. French supremacy over Vietnam was all but assured by then, and looked like it might have lasted forever.

Creating a liberation movement

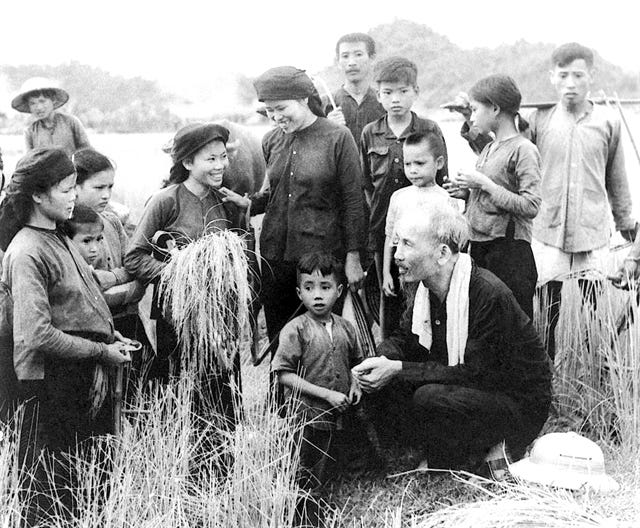

It’s in this context that Ho Chi Minh was born in 1890, in a rural village, to a teacher and a weaver. In 1905, he was admitted to the French primary school in Vinh City. There, he was — perhaps perversely — introduced to the French Revolution by his teachers. At this time, protest and unrest was rampant in Huế province, which his family had moved to in 1895 as his father prepared to take the Mandarin exam.

What’s interesting to note, beyond the mere biographical facts, is that Ho Chi Minh was a driven person. In that way, he wasn’t anyone special: he simply applied himself, diligently, towards a goal — the freedom of the Vietnamese people. He got his start politically by participating in the protests in Huế as an 18-year-old, which were brutally repressed by the colonial police. After that, he left on a merchant ship, and travelled the world for a time. It’s interesting to note that while working as a kitchen worker in the Carlton hotel in London, he still found time on his one day-off per week to learn English and Esperanto. While living in France, he eventually joined the newly-founded Communist Party in 1921 after reading Lenin’s Theses on the National and Colonial Questions, and was a member of their Colonial Committee. In 1919, he petitioned Woodrow Wilson and the French government to grant the Vietnamese people their civil rights and right to self-determination. The petition failed, but made some waves in Vietnam.

His political activities got him in trouble with the French police who tried to arrest him more than once, and he eventually had to leave France — partly because of his activities, but also partly because his goal was the independence of Vietnam from colonialism, and he had to go back eventually. His routine had become predictable to the police: in the mornings, he would go to work. Then in the afternoons, he would go to the local library and read books (showing once again his commitment to reading and learning as much as possible). In the evening, he would go to party meetings and then went home at night. The plan was calculated so that one day, the police became complacent; they only monitored him up until he took the bus to go to his party meetings. One evening, he boarded the bus and, as the police left, he instead went straight to the train station where a friend handed him train tickets.

From there, he travelled to the Soviet Union for a few years, again learning and teaching himself as much as he could in the process. By then, the year was 1924 and Ho Chi Minh was 34 years old, a long way from the young adult who participated in protests in Huế! After a few years spent in the Soviet Union, he travelled to southern China — which was at the time the Republic of China — and founded the League of Oppressed Peoples of Asia there, regrouping Chinese, Korean, Indian, Thai, Indonesian and Malaysian (all colonized countries at the time, with the exception of Thailand who was more of a comprador state) nationals exiled in China. He formed a political training class which gave courses over several months to these students.

We can see from this short biography three major points that resume Ho Chi Minh’s life so far: he was always reading and learning new things, he was politically active, and, most of all, he then passed this knowledge on. Education and political activity go hand in hand, and in that way Ho Chi Minh was no one special; he was human like everyone else. But, like many other influential figures, he followed these precepts: reading leads to learning leads to teaching leads to agitating — a very important last step that is often completely occluded, where people prefer to learn for the sake of learning but never apply.

Ho Chi Minh had to leave China in 1927 after Chiang Kai-Shek’s coup, and he spent several more years travelling the world, making contacts and politically agitating. But in 1940, everything changed: Japan invaded Vietnam. This forced him to return to his home country in 1941. By then, Ho Chi Minh had made a name for himself in Vietnam: he had founded the Communist Party of Vietnam (later renamed the Indochinese Communist Party) over a decade ago. He had travelled the world and made contacts (including in the Vietnamese diaspora), and so he did not return to Vietnam as a stranger as a complete stranger, but as someone who had already showed his intentions and made a name for himself.

The Japanese occupation

The conditions in Vietnam had changed and from this point on, everything suddenly moved very quickly. The armed invasion by Japan — though allowed by Vichy France (the puppet government set up by Hitler after the invasion of France) — was even more brutal than French colonial rule, and created a microcosm of contradictions. While the Japanese controlled Vietnam militarily, France controlled it administratively — and Vichy France was far from being as strong as the peace-time French Republic had been. Japan itself, while garnering victories in Asia, was on its way out as an imperial power by then. The Meiji Restoration, started in 1868, had given rise to the imperialist power so that they could industrialize rapidly to be on par with the western world, but by the 1940s the restoration had hit a wall and was well on its end, which is why the empire invaded China in 1933. Since much of Asia was also held by colonial countries, and the empire inevitably had to seize resources and labor in these colonies, they found themselves forced to invade the Philippines and other US-held colonies. All of this propelled them into war with the United States in 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor (in occupied Hawai’i) being only a symptom of what was required to continue or, rather, kick the restoration back into gear. In other words, even by 1941 several powers and figures already knew that Japan would not last long in its occupation and was stretching itself thin.

As soon as he returned in early 1941, Ho Chi Minh convened the 8th Central Committee meeting of the Indochinese Communist Party — relying on a base that he had helped establish years before, and not starting from scratch at the height of the invasion — where the party agreed to found the Việt Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam), a broad coalition aimed at rallying all patriotic Vietnamese against the occupiers. They prepared for armed resistance, and began organizing revolutionary bases in the north of Vietnam, using the geography to their benefit. There, they trained fighters and cadres and rallied support to their cause for the independence of Vietnam; as mentioned, the Viet Minh was a broad coalition and accepted anyone who wanted to fight for independence.

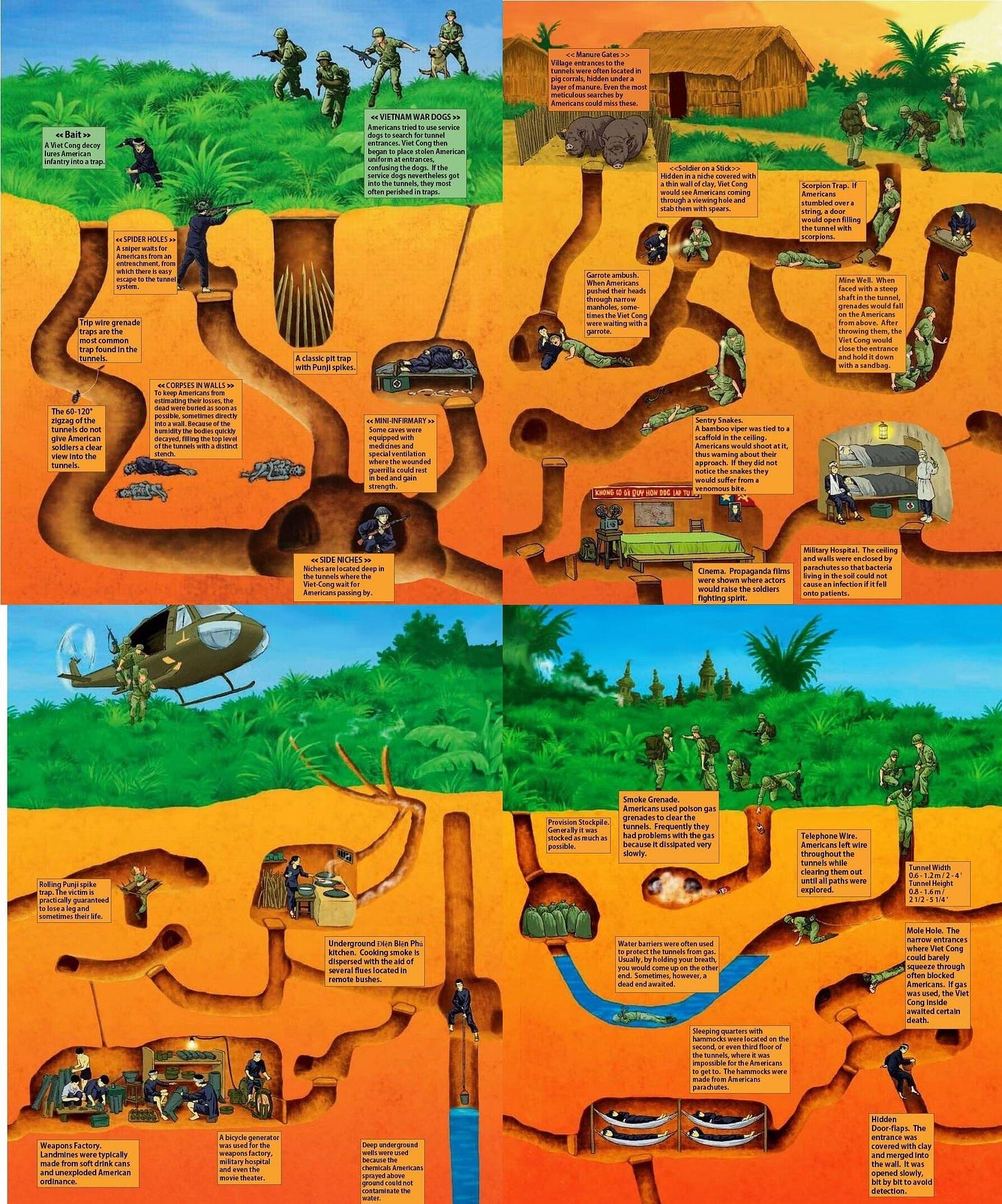

During the war, that is, until 1945, the Viet Minh primarily fought guerilla engagements. The time was not for peace anymore: the purpose of Ho Chi Minh’s missions throughout the first half of the century was for building a base of support and agitating for revolutionary consciousness. When the invasion happened, this base was forced to kick into action, no matter how weak or strong it may have been at the time. They conducted raids on Japanese facilities, notably seizing food that they distributed to the people to alleviate the famine conditions. In areas the Viet Minh controlled, they promulgated land and labor reforms: they abolished the system of forced labor (corvée), redistributed farmland equitably, and established literacy programs.

These reforms helped build popular support, which served two purposes: it made more people want to join the resistance, and it made them sympathetic to the cause and less likely to sell out resistance fighters or align with the occupier. But beyond the immediate gains, these reforms show that politics are inextricably linked to armed struggle (or the other way around, in any case). It was not sufficient to simply resist: further goals were at play. In other words, the Viet Minh were not a mindless fighting force who was going to disband after the war. The war was just a temporary roadblock on the road to independence, and the only thing one can do is act within this situation properly. Building a base of support at home was useful to the Viet Minh during the war, but it would also be useful after the war, because it showed where their interests lied and what people could expect from the Viet Minh (or rather, the Indochinese Communist Party) politically.

In late 1944, Hồ Chí Minh directed General Võ Nguyên Giáp (remember him — he will come up again later) to establish the Vietnam Propaganda Liberation Army, the precursor to the People’s Army of Vietnam. By that time, the Viet Minh controlled large parts of northern Vietnam, having liberated six provinces and establishing their own forms of government there. These victories owed to tactics and the leased equipment they received from China and the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor of the CIA), making purposeful use of the terrain: much like in China, the Japanese only really controlled urban centers and railroads. Outside, their rigid structure found it difficult to properly control the rural areas and the jungle environment. When the enemy’s bastion is in the cities, then the revolutionaries must make their bastion in the countryside, from which they built an army, amassing forces to take on the invaders. This is another lesson we can learn from this struggle.

Japan’s defeat became evident by mid-1945. Quickly, the Viet Minh formed the National Liberation Committee and called for a nationwide revolt. Using this momentum, they marched to Hanoi and other cities in northern Vietnam and captured them back from the occupier. On September 2, the same day Japan surrendered to the Allies, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam — completely ignoring any French opinion about the matter, as indeed France was not in a position to do anything about it, if they dared.

War against France

The Liberation Army formed in 1944 was still very small. By September 1945, it recorded approximately 1000 members. But, it was a necessary step to establish a formal army if Vietnam was to become sovereign.

The move did not come a moment too soon. While the Viet Minh had a strong presence in the north and announced a free Vietnam (thereby declaring their intentions to free all of Vietnam and not just the north that they controlled), the situation in the rest of the country was a little different and not so clear-cut. The French quickly scrambled to come back and occupy Cochinchina, which, if you remember, was the southern colony in older times. They had occupied Vietnam once, and were not going to relinquish it, despite colonies not being as crucial in the post-WW2 world as they were in the early days of capitalism and free markets — this is another lesson, learned from the enemy, that they will never agree to your liberation until they are forced to. Agreements were signed but were short-lived, buying a little bit of time for both sides. In late 1946, the French Navy bombed the port at Haiphong, causing thousands of civilian casualties. The Viet Minh launched an uprising in Hanoi, and thus a new war started.

Vietnam was now divided in two, with the French areas in the south, and the independent Vietnam in the north — as a precursor to the US-Vietnam war a few decades later, the US quickly recognized the French Vietnam while refusing to recognize the actual, well, Vietnamese Vietnam. Much like they had done against Japan, the Viet Minh fought with guerilla tactics against the French, using the terrain to their advantage. After 1949, with the Communist Party of China winning its own civil war, Chinese aid to the Viet Minh (in the form of weapons, training and logistical support) increased to match the power of the French. But first, the Viet Minh needed to free the border. They inflicted major defeats on the French at Đông Khê and Cao Bằng in 1950, which opened up the border with China and allowed for the aid to come in.

As the French were facing a sure defeat (in due time), the United States provided them with military assistance — by 1954, this aid accounted for 80% of France’s war expenditures.

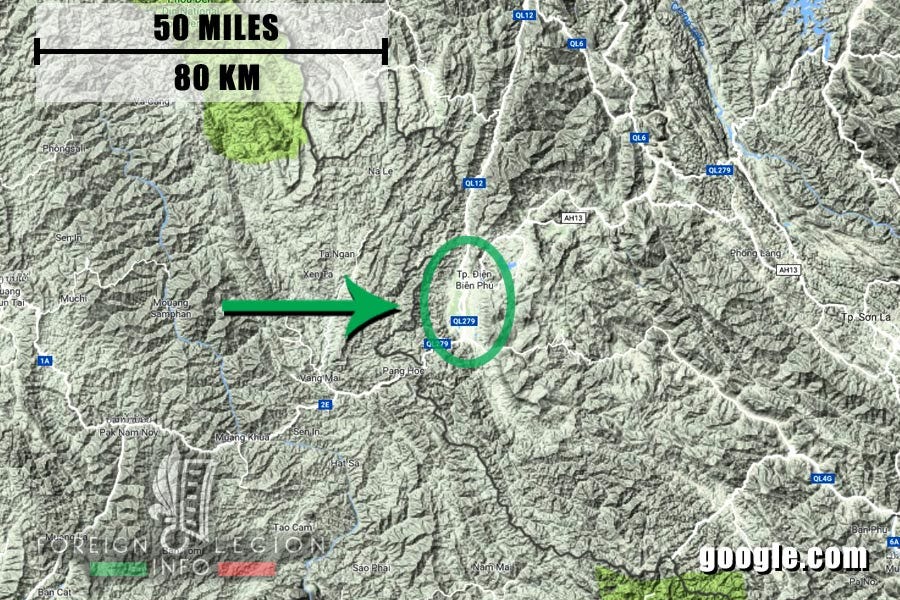

The French had to change plans, and they tried a foray in the north again, aiming to force the Viet Minh into more favorable negotiations. This led to the establishment of a fortified base at Điện Biên Phủ.

The battle of Điện Biên Phủ

The base was not a historical fortress. Điện Biên Phủ, located in northwestern Vietnam near the border with Laos, was (and still relatively is) a mostly undeveloped region. The point of establishing a base there was to lure the Vietnamese forces into a conventional engagement. On paper, everything had been perfectly picked: the location was in the Mường Thanh valley, surrounded by tall hills and mountains. The French also used Laos as part of their logistical network, allowing them to somewhat easily build and reinforce the base by air. The base was meant to interfere with the Vietnamese forces and thus force them into an engagement, but it was also placed right in the middle of the Democratic Republic’s territory.

The French mainly expected that the tall hills and mountains surrounding the valley would deter most offensives, and instead funnel the Viet Minh forces through the narrow gulleys in which French artillery could easily fire.

And yet, as history shows, the Vietnamese forces proved to be more cunning than their occupiers. General Võ Nguyên Giáp led the battle — the General Ho Chi Minh had named to lead the People’s Army years earlier. Instead of playing into the French hands, they realized an impossible feat: they transported their artillery up the hills, over several dozen meters of elevation, and reassembled the batteries at the top of the hills all around the valley. In some cases, when the terrain did not allow for it, they instead dug extensive tunnel systems through the mountainside, from one side to the other, so that they could roll out the artillery at the mouth of the tunnel, fire a volley, and then quickly move it back inside for protection. They did all of this without air support or motorized vehicles. Instead, they used plain manpower and animals, enlisting the help of thousands of workers from nearby communities. At the top of the hills surrounding the base, they stealthily reassembled the artillery, and waited for everything to be ready.

On March 13, 1954, the Viet Minh launched their first major attack from this advantageous position, taking the French completely by surprise. They targeted key outposts protecting the main base on surrounding hills, capturing them in just a few days. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese artillery pounded the main base, taking out communication relays and airstrips, which left it entirely isolated and left to fend for itself.

In the second phase, after the outposts had been taken out, the Viet Minh used a trench system they had dug to advance closer towards French positions while shielding themselves from their fire. The strategy General Võ used was one of “steady attack, steady advance”, preparing for a long siege, which he picked after having studied the French positions and defenses in the area. The Viet Minh were not in any rush: the French were sitting ducks there.

In just 56 days, the siege was over. A funny anecdote is that early on in the battle, the French commander of artillery committed suicide at the base upon realizing that his artillery was utterly ineffective against the Vietnamese positions. All in all, over 16,000 French troops at Dien Bien Phu were killed or captured during the siege.

Everything moved swiftly from then on. With this major defeat in tow — the one of many — France had to accept less favorable terms at the negotiating table. The Geneva Conference had been convened for a month before Dien Bien Phu, but negotiations take time, with both sides wanting to delay them for as long as possible until they can achieve a better position. With the taking of the base, French capabilities in the north were entirely wiped out, and the French government correctly understood that there was no miracle operation left for them.

A ceasefire was declared, but more pressing was that Vietnam was “temporarily” divided at the 17th parallel, much like Korea had been just a few years earlier. The north came under the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DPV), and a puppet State of Vietnam (which would survive into the US invasion) was created in the south.

This situation was of course far from ideal, but from the DPV side, it made some sense to accept this. Vietnam had not entirely been liberated yet at that point in time, the French still controlled most of the south. To push south would have meant to continue the hostilities for potentially several more years, and with no guarantee that another situation like Dien Bien Phu would come up. On the contrary, it was more likely that the French would play more defensively from then on. Conversely, accepting a parallel Vietnam state would be more conducive to either a diplomatic resolution, or the resuming of hostilities, but this time without western involvement. This is another lesson we learn from this struggle, but of course, considering the later US invasion (and outright deployment of US troops), we know that this may not be a true lesson. That is, the real lesson might be that one must be ready for a protracted struggle. Would the DPV have won over the entirety of Vietnam had they refused the negotations and kept fighting against the French? Perhaps. We unfortunately can’t peek into alternate timelines. But perhaps the United States would have still sent in their G.I.s had the Viet Minh been a little been too successful, and Vietnam would have found itself in the same situation it did historically: fighting a fake puppet state in the south backed by U.S. money and soldiers.

At the convention, national elections were also agreed upon to take place in July 1956, or two years from the time of signing. These elections were meant to be held over the entirety of Vietnam. However, the southern state reneged on that promise when the time came in 1956, as they knew that Ho Chi Minh would win national elections (with no surprise, as the Viet Minh had been fighting for the Vietnamese and building dual power in the areas they controlled, showing the kind of policies they would implement). The prime minister of the southern state was Ngô Đình Diệm, who would play a role in the later Vietnam War. If you remember the famous picture of a Buddhist monk meditating (or appearing to be) while setting himself on fire, that came from Diem’s time as president of south Vietnam — as a Catholic, he suppressed the Buddhist majority. That is perhaps what he is best remembered for before being assassinated in a coup in 1963.

At the time in the 1950s though, he went back on the Geneva Accords that he previously agreed to. Much like in Korea, Diem organized his own referendum in 1955 to depose emperor Bảo Đại, whom the Geneva Accords placed as head of state, so that he could declare himself president and thus proclaim his own sovereign state. Then, in 1956, he held elections for a national assembly of his own, making sure to staff it with supporters of his regime. The DRV, who had absorbed the Viet Minh into its conventional army, correctly condemned the actions as a US-backed plot and called out Diem for, quoting, “trampling on the nation’s desire for peace and unity.” The DRV continued to advocate for a diplomatic reunification while supporting southern resistance cells but, as we know, this did little to change the situation (although it did solidify the DRV’s commitment to peace, which by comparison made the US look like a warmonger on the international stage).

It was at this time that the United States fully committed to supporting the southern regime. From their point of view, it was a bulwark against communism in Asia — especially as they “had” to contend with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, China, and the Soviet Union in the region.

Thus began the Second Indochina War, just as soon as the first one had ended. As we know from the current situation, this second invasion ultimately failed, and today a free, sovereign and decolonized Vietnam is proof of that. The imperialist plot to permanently split Vietnam in two failed.

All in all, the struggle lasted for almost 100 years, if we count from the time of Ho Chi Minh’s birth in 1890 to the end of the war in 1975. But, it succeeded and continues to succeed every day.

To summarize, the lessons from Vietnam’s struggle are thus:

A movement is built over decades, and this must begin before its support is needed. It is built both at home and abroad.

When the time comes, people will leap into action if they have something to fight for. The time comes when the movement decides it has come, not when things are ordained perfectly in the perfect configuration for the perfect outcome. Hence it is primordial to build this movement in advance.

Liberation struggles very often require a war to succeed. Freedom is never granted by the oppressor.

Not everyone will be (or has to be) a soldier, but it is crucial to be able to rely on a wide support base for logistics, protection, food, etc.

A support base is cultivated and continues to be built as part of the movement even during times of war. To lose the base means to lose the struggle.

To do things for the people means to show them what policies succeed. Dual power (a parallel state built even under occupation, with its own laws and policies) shows how the liberation movement works in practice.

Do you notice any more teachings from this struggle? Feel free to write them in the comments!

Such a fascinating history! If I were to add another lesson from Vietnam to this list, it would probably be that struggle may not only last decades, but should be viewed as intergenerational. It's a practice of radical hope that allows us to see the horizon beyond our lifetimes. Thanks for this, Crit!

What a fascinating article with many lessons. We need many more ho chi mins today