The blueprint of regime change operations

How regime change happens in the 21st century with your consent

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like and restack! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

Resources are getting scarcer with every passing year. Water itself, for example, is becoming difficult to procure in some regions as climate change transforms them in unpredictable ways, making fresh water an increasingly rare commodity. Already finance magazines such as Bloomberg are salivating at the growing market for this vital resource.

In this difficult worldwide situation, procuring access to much-needed (and profitable) resources is becoming a very competitive race.

But it’s not the only challenge that we’re facing today. Companies face their own challenges too, as markets are transformed, appear and disappear. We now live alongside giant multinational companies

This is how we get to acts such as regime change, which involves destabilizing a country so that we can get a friendly President or dictator in power who will let us access these rare resources. This is however only one facet — only one possible act in thousands — of a phenomena known as imperialism.

Understanding imperialism

By imperialism, I don’t mean the old policies of the 18th century of conquering land left and right and scrambling to grab whatever piece of territory had not yet been claimed by a stronger power. I mean the very rational, very methodical process by which some countries indefinitely remain poor while others get richer. The process which made EU Vice-President Josep Borrell say “Europe is a garden; the rest of the world is a jungle.”

The world is rich.

I don’t think I’m saying anything outrageous or original there.

The world has lots of natural resources which are transformed, bought, and sold on a global market.

Since the second half of the 20th century, we especially rely on oil, or petroleum, to power our lives. We heat our homes with it in Europe (or technically with a byproduct of the petrochemical refinement process). We drive cars with it — in other words, oil lets us travel and we could say it literally makes the world go round. We make plastic, rubber, even textiles with oil.

Another important natural resource is natural gas, which we also use as a fuel source over the world. Rare (or semi-rare, such that they are not found in every geographical area) elements such as cobalt, lithium, and manganese have also soared in terms of demand since everything nowadays runs on batteries and a small computer — even your car, your microwave, or your alarm clock (which is likely to be a smartphone!)

You might think that there’s not really a reason to go to war over these materials. But here’s the trap: if you don’t control those resources, someone else will. And they will profit off of them while you won’t.

The reason this might seem far-fetched reasoning to you is because you’re an average worker. You go to work, come home, and get paid for it. But the oil barons and other billionaires don’t think the same way, simply because they have too much money at stake to let it sit idle. They need to think about always making more profit: if they don’t, someone else will. And maybe eventually that someone else will overtake them, and leave them bankrupt.

It’s driven by real material, on-the-ground, realities. It’s the reality of capitalism. The bigger fish (i.e. the business) eats up the small fish, and so you have two choices: either grow into the big fish, or get eaten by one. Everyone is trying to get their spot, nobody starts a business on humanitarian reasons — it’s all about profit.

This reasoning never stops, even as you become a billionaire. Because there’s only so much wealth that can come back to you, you want to have it for yourself rather than let someone else have it. You need to grow.

At first, you’ll corner your market and run the competition out of business. You’ll sign exclusivity deals to provide a service so that nobody else can compete with you. But you’ll eventually run out of market shares. There’s only so many people in the state or country that will or can purchase your service.

You’ll then start branching out into other services, but that only goes so far. You need to invest millions to launch a new product and the market for it might not grow very quickly, forecasting a return on your investment not before 5 or 10 years.

AT&T for example is present in all US States and, like all telecom companies, has signed under-the-table deals with the ‘competition’ to stop competing with each other. They fix prices around similar plans and have promised to stop competing with each other on this aspect. But they still need to grow, because they have shareholders who demand dividends and who want to sell their shares for a profit, and shares will only go up in price if something happens to reflect the increase in price.

If you have trouble visualizing that, just listen to mainstream economists: when GDP growth goes in the negatives for over 3 months, we technically enter a recession. Instantly, thousands lose their jobs in “cost-saving measures.”

In Europe, we have privatized energy companies, which used to be state-run and had a monopoly on the entire territory. Now, some other energy providers have popped up but by and large, the previously state-owned companies are run in the interest of profits, not of the people. Everyone needs electricity and heating anyway, and so there’s not much more market you can conquer when the entire country is already your client.

Slowly, we naturally move into imperialism as a rational process.

When there are no more markets to get into, you need to open new ones up. There are various mechanisms for that.

How China was forcibly opened up

In the 19th century, two wars were fought by the British in China to open up the rich, populous country to foreign markets. China had been mostly reserved towards the Europeans, only allowing foreign merchants in at the port of Guangzhou (through which they sold to Chinese merchants who then sold to the Chinese population). This displeased the British who wanted to cut the middleman for themselves — while not letting other countries beat them to it. They attacked China twice with help from the USA and France (realizing they could never force China to submit without help), forcing them to open more ports and cities up to their merchants.

This war happened because the Kingdom of Great-Britain sold Indian cotton and their own silver reserves to China, with the proceeds being used to purchase tea (at the time, only China produced tea, until the British stole a tree to start their own production), but they were clearly heading towards bankruptcy over this trade deficit and needed some way to balance the budget.

The British couldn’t have stopped importing tea either, because it made a lot of money to their merchants when they sold it back in Britain. It didn’t matter to the merchants that Britain was depleting its silver reserves, all that mattered to them was seeing the shillings and pounds fill up their pockets when they sold the tea.

They decided opium, which they grew in India and stockpiled a lot of (since more and more countries realized the dangers of opium and started banning it, creating a large stockpile of it), would be able to fill the hole in the treasury. China, of course, didn’t want opium to infect their people and devastate the country and would never willingly agree to let opium in.

To get opium into China, a war — the ‘continuation of politics by force’ — was declared.

At the end of it, China was forced to accept foreign merchants into some of its ports and had to give them special status, which let them sell opium on the streets without repercussions. This started the Century of humiliation in China which greatly devastated the country. At its highest point, it’s estimated 13 million Chinese (out of 400 at the time) were addicted to opium.

But it didn’t matter to the British. They could now sell their opium and bring back profitable tea. It was a win-win situation for them.

Today, we are less overt in our imperialist endeavors. We might not even go to war, and we have developed mechanisms after Bretton Woods (1944) to rein in countries that, just like China, do not want to play by our rules.

Why we do this

Europe doesn’t own a lot of natural resources. At least, not enough to cover the worldwide demand — we can’t even cover our own domestic demand with our own resources. We do have some crude oil (Russia, UK, Italy) and oily sands (Norway, Sweden). But this only accounts for 10% of the oil we consume every year.

Although, it should be understood that the oil produced in Europe does not all stay in Europe. It’s more profitable to sell it to other countries sometimes, and so it will freely be sold abroad. Likewise, we then import foreign oil that might be cheaper than the local product. Worldwide markets have become very integrated after World War 2.

Likewise, we don’t have lithium (only Portugal, and very little) or silicon. We only produce uranium in the Czech Republic and Romania.

The rest of the world is very rich though, and we can get resources there. But how?

You could go the legal way and open a business in a country that has oil or lithium. Open a mine, hire workers, and get them to work.

But the host country likely won’t want you to exploit that mine for very long. As soon as they are able to exploit it themselves, they will kick you out and take possession of it. After all, why shouldn’t they profit from their own resources? Why should you have sole ownership of them? Because you paid for it? Well, they’ll buy it from you at the price you paid for it.

This is how imperialism sets in. It’s vital to not only keep access to natural resources, but also to make sure you can mine them on the cheap (with access to cheap labour or friendly dictators that won’t tax your revenue).

Again, I want to highlight how this process is very rational. Some business owners might not even realize they participate in it, but they need it all the same.

It’s how we get our cheap treats in the West.

Chocolate for example has become known as a European product. Belgian and Swiss chocolatiers especially are famous in the entire world.

But Europe doesn’t grow cocoa — the climate makes it impossible. So cocoa is grown mostly in Africa, despite being a plant native to the Americas, brought to Africa and the world over by colonization.

Would it surprise you to learn that while we’re able to buy chocolate any time we like, cocoa farmers in the Côte d’Ivoire have never even tasted chocolate? It’s a luxury for them, and one they can’t afford.

This is because we make sure we get to have access to cheap cocoa, and prevent cocoa-producing countries from making their own chocolate so they can’t compete with us. This keeps the price of chocolate artificially low so that we can buy it as a tasty treat (helped with some good marketing campaigns).

This is the real cost of imperialism. It’s not solely about monopolizing resources so that the competition can’t. There’s a real human cost behind it; the billions of people who prop up our lifestyle by living on poverty wages. They work in low value-added industries, which means their country as a whole can’t really develop.

In 2019, when Bolivian President Evo Morales announced he was going to nationalize the lithium industry, he was replaced by a military junta led by Janine Añez as the Organization of American States, a US-led ‘organization’, worked to invalidate his election, with a statement that was uncritically repeated by the media. They never retracted their statement or admitted the part they played in delegitimazing Morales’ election.

Morales’ plan was to stop solely extracting lithium and exporting that raw material, but also transform it into batteries and other finished products which have a much higher margin on the market. Instead of selling raw lithium, which makes say 1$ in profit per ton, Bolivia would have started selling batteries for, say, 10$ in profit per battery.

But here is the trap of imperialism: the owners of the lithium mines want to profit on the raw, low-value added material as well. And so they reduce wages (the one factor they can easily control), they extend working hours (effectively reducing wages), they remove safety measures (reducing costs)… the cost of imperialism is reverberated all the way down from the top to those who actually make this value possible, the workers.

Morales’ plan would have made Bolivia compete with our own battery-makers, which we can’t have. If someone else gets access to the market, it will cut into the profits of our bourgeoisie, the owners of the means of production. Worse yet, as they own the whole supply chain, they could actually offer better, cheaper batteries than we do and will eventually likely drive our own battery makers (who won’t get the lithium to make them) out of business.

Thus Morales was ousted from power in a week, a week during which peaceful pro-Morales protestors were shot and killed by the military junta ruled by Jeanine Añez. Interestingly, while the coup was ongoing and before Morales left, the same newspaper that reported on the violence above (the Guardian) wrote a scathing piece on Morales and reiterated several times that he faced public protests — only focusing on the anti-Morales camp and not reporting on the much bigger pro-Morales protests.

The blueprint of an imperialist operation

Now that we understand what imperialism is and why it happens in the modern day, we can look at how an operation is conducted.

Over time, we (the West) have become very good at doing this kind of thing. We’ve refined our regime change operations to a playbook that one only needs to follow.

These are the steps.

First, the target country is selected. We’ve seen Bolivia above, but we’ve also seen countries such as Russia, Iran, China, Syria, Iraq being targeted. There are frankly too many to count. We count on this characterization of the rest of the world as a ‘jungle’, as Borrell put it, as a cover for our imperialist operations. By making you think the rest of the world is simply incapable of developing and it’s the ‘garden’ against the ‘jungle’, our governments hope you will feel complacent when they announce the next target. They hope you’ll think “Oh, who cares, there’s always something happening anyway.”

You can’t allow yourself to become complacent to what’s happening in the world.

The second step, once the ‘enemy’ is selected, is to start publishing stories. People trust the media implicitly, and many also trust the government even if they might not trust the President. Something very devious happens then:

In the first phase, the government releases a statement or report about ‘concerns’ in the target country. This could be human rights abuses they ‘noticed’, ‘irregularities’ in the presidential election (like the OAS said about Morales), a political organization that’s being ‘censored’ (like in Belarus), etc.

In the second phase, the media prints out those reports uncritically. Their job is to get it in front of your eyes. They also run their own stories that confirm what the government has been saying but in their own words, disguising it as an independent investigation.

Essentially, we cover all our bases. If you don’t trust the government, you’ll trust the media that’s reporting on it. If you don’t trust the media, you’ll trust the government reports. It’s a self-feeding mechanism that grows bigger and stronger with each new report, article, and fabrication.

During the second phase, we see that the stories are sent to the media in many ways. CIA assets for example might write articles for a newspaper (Edward Hunter was such a journalist who defended the invasion of Korea in the 50s; he was also a CIA agent). Most of the time, the media will happily print the reports though. See for example Reuters, which was created by the British — and covertly received funding from them — to expand their operations in the Middle East at a time the British were busy destabilizing governments in Yemen, Iran and Saudi Arabia (if you didn’t know by the way, the British installed the dictatorial house of Saud in 1932).

Sometimes, government-connected NGOs such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty will also put out their own reports. Suddenly, it’s all you see on the news. Amnesty said this, Blinken said that! While only a few days ago you didn’t know the first thing about Belarus, Bolivia, Eritrea or Myanmar, suddenly you’re expected to be an expert.

In this stage, stories come out all the time. It’s all the media talks about. Russian invasion of Ukraine, irregularities in the Bolivia election, Iran’s nuclear program… the media cycle focuses on this one issue and it seems they always have something new to say.

‘Experts’ are brought in to explain how the enemy country is very bad and that you should listen to the media. They will use statistics, law, history, philosophy, sociology to explain every way in which the enemy country deserves to have its government forcibly changed. Really, we’d be doing them a favor by meddling in their politics and installing our own candidate in government.

You certainly feel like you’re becoming an expert on the situation. There’s more coverage coming out than you could consume. The media use very simple language that anyone can understand, almost as if they were giving you a gold sticker and saying “good job for understanding the situation!” But in truth, you’re only understanding the situation they feed you nonstop.

Freedom fighters appear

At the same time, groups and individuals in the target country are being activated. They repeat the exact same points our media and governments have already conveyed. These groups are funded and trained by our governments — the ‘moderate rebels’ in Syria, the ‘students for democracy’ at Tian’anmen, or individuals such as Joshua Wong (who received funding from the National Endowment for Democracy through his party Demosisto) or Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya in Belarus, who was funded directly by the EU.

These groups and individuals are suddenly propped up in the media as well. They get invited to talk to Congress (Zelensky, Wong). They get invited to talk to the President, or other high-profile politician — always in huge ceremonies with dozens of journalists. Smiles are exchanged, and the message is clear: “I like this person, so you should too”.

These groups are presented always in a good light, as freedom fighters representative of the whole country, fighting a David vs. Goliath battle against a tyrannical persecuting government.

These groups and individuals are very important. They show that our policies against the legitimate government have basis. They show locals support us. Of course, we don’t talk about the funding we’re giving them or about the locals who don’t support us.

They come out of seemingly nowhere. Who among you knew about Joshua Wong before his involvement in the Hong Kong riots in 2019? Did you know about Zelensky before the war?

These plants make a lot of money out of it, and that’s why they sell out their country. The US will fund them millions — just go see how much money the NED, a CIA front, grants every year to organizations. These individuals and organizations’ role is to take up leadership after the coup has succeeded, and be friendly to the USA. They will privatize state assets (Chile, Ukraine, Afghanistan…), they will repeal labor rights (all of the ex-USSR), and when they’ve made enough money selling out their country and compatriots to their imperial masters, they’ll flee to occupied Hawaii to enjoy the rest of their lives in peace (Syngman Rhee).

Up to this point, we have what’s called a color revolution. This works really, really well. It makes it seem as the opposition is popular with the masses. In reality, in the case of HK for example, only 25% of the country supported independence — while Joshua Wong was pushing for it in the US Congress as he was claiming to speak for all Hong Kongers.

Meanwhile, the target country and its legitimate, elected government is being presented as unreasonable, oppressive, trying to stifle free speech and democracy — values which we feel strongly about. When they correctly call out our plants for being funded by foreign interference, they get called lunatics or as trying to shift blame. When they arrest our plants, it’s further proof that the President has something to hide and he stifles free speech.

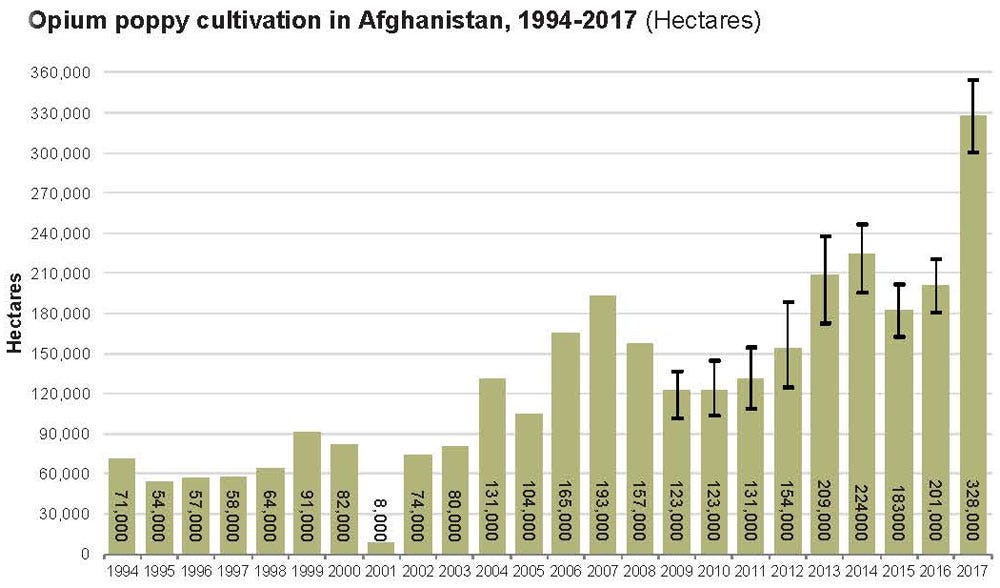

In Afghanistan for example, which US and NATO troops have been present in for over 20 years (only to get unceremoniously kicked out by the Taliban, the group they were supposed to be fighting for those 20 years), installed a friendly government soon after the invasion in 2001. Under Ashraf Ghani and Hamid Karzai, the only two Presidents the US-installed government ever had since 2001, opium production became a huge business in the country.

This is, incidentally, a reason the Taliban was so popular with the masses in Afghanistan and could democratically be considered the rightful government (following our own rules, for once, of the most popular candidate being elected).

Since 2019, opium production has been once again banned by the Taliban in Afghanistan. The Taliban also put an end to rampant child abuse and pedophilia in the country that proliferated under the US-collaborationist government with their help.

Any attempts the target country makes to explain itself is either ignored or blocked. Their ‘excuses’ will not be printed in the media. If they try to get a UN delegation to visit, the Security Council will veto it (with the USA, France and the UK as permanent members). If they publish seized documents, they’re called fakes. If they hold a proper trial for individuals, they’re called kangaroo courts and fake trials.

Sometimes, it doesn’t need to go much further than this. We will keep funding, arming and training dissident groups that we can get to our side, with little regard to who we’re actually funding — the US funded the Taliban against the Soviets, for example, which later created Al-Qaeda. When Al-Qaeda was disbanded and ISIS was created, the Pentagon started funding ISIS in Syria against Bashar Al-Assad.

… and this is enough for a coup to happen internally without needing more overt involvement. This is what happened in Ukraine for example in 2014. Viktor Yanukovych was elected in 2010 and happened to want warmer relations with Russia (a wise decision, considering they share a border & history and used to be part of the same union). Russia, however, is a strong country with no weaknesses to exploit and “imperialize” them. Oh, but they tried though. The breakup of the Soviet Union itself was fueled through a color revolution, and Yeltsin won the 1991 election with funds from the USA. When Putin won against Yeltsin in 1996, he originally got close to Western leaders such as Clinton and Tony Blair, who were hoping they could control him like they did his predecessor.

Tony Blair, then Prime Minister of Britain, went to meet the newly elected Putin in St-Petersburg in 2000. At the time, the West really thought it could turn Putin into their Yeltsin and make him sell off the vast state-owned enterprises of the ex-USSR to European and American capitalists. They had lost Yeltsin and their ‘investment’ in him, but that didn’t matter. What mattered was if they could get the next President in their pocket.

This plan, however, did not materialize as Putin had entirely different ideas in mind. Shortly after this plot failed, Putin became Europe’s public enemy number 1 and we’ve been overwhelmed by stories of the ‘Russian dictator’ in the media ever since then.

To briefly explain Boris Yeltsin, he was a bumbling alcoholic who polled in the single digits at the time of the 1996 election, which would have been his reelection. Previously, he had been the architect of the dismantlement of the Soviet system that brought about a humanitarian crisis that destroyed the GDP per capita and life expectancy in Russia.

In 1996, seeing the writing on the wall, he colluded with then-US President Clinton to help his reelection. It didn’t work, and Putin was elected instead.

In the 50s, the USA used to be more overt. They had just come out of WW2 stronger than before, and with all of Europe devastated, there wasn’t really anyone to challenge their power — especially not the Soviet Union, who lost 20 million people to the war and had to rebuild their invaded and destroyed cities.

This in-your-face overtness makes earlier color revolutions much simpler to follow and explain. We also have historical hindsight and so many years have passed that we now have all the facts and documents and can trace US involvement all the way back to the source.

The USA took Cuba from Spain in 1898 after a war. At first, Cuba became a colony of the USA — pretty much the same status it had under Spain. However, it proved too difficult to manage as Cubans understandably did not want to replace one oppressor for another (especially as they had fought against Spain in the war). As such, Cuba was quickly made ‘independent’, but always with the consideration that the USA would pick the Cuban president through ‘democratic’ means. They might have had elections, but these elections always ended with friendly US-backed Presidents.

In 1944, San Martín was elected President, with a goal to break the dependence of Cuba on the USA. Cuba had just come out of the de facto Batista dictatorship (which he ruled through ‘democratically elected Presidents’). This did not please the USA who wanted to keep their prostitution and gambling vacation den subservient. San Martín was replaced by Socarrás in 1948, who was originally much closer to the USA. However, Socarrás had plans of his own and, through the second half of his mandate, started promoting a more independent Cuba. Again, this did not work in the interests of the USA who had him replaced.

In 1952, Fulgencio Batista finally seized power for himself in a military coup, once again backed and funded by the USA. He ruled Cuba as a dictatorship until the 1959 revolution. Batista had become irreparably toxic in Cuba, ruling with an iron fist. As such, when the revolution started, the US was happy to see how it played out without much intervention (aside from the arms and funding they had sent him in the years leading up to the revolution). They ran their models and predictions, and decided they might be able to control this ‘Fidel Castro’ newcomer as well.

Early after Castro’s coup against Batista succeeded in 1959, he was invited to the USA and approached by then-President Eisenhower. He was paraded in the streets of New York City as a freedom fighter. Marvel was even commissioned to make a comic book about him in October 1959.

Castro, however, was not naive enough to believe the United States could ever be a friend. He masterfully defied their expectations when, only a few months after he took power, he nationalized all industries, expropriated all the land, and set out to create a truly independent, revolutionary Cuba.

This failure in US policy to control Castro led them to suddenly cut all ties with Cuba and enacting, for the first time, the embargo that has been going on against Cuba since then, and which has cost Cuba an estimated 150 billion USD. The goal of this sanction against Cuba (which the UN votes every year to declare illegal, with only the US and Israel voting against the resolution) is to slowly starve out the country and make the legitimate government (now led by Diaz-Canel) unpopular with the masses so that a pro-US dictator could be put back in Cuba. They hope to create the conditions for a color revolution with this interference, and we can see they tried for example with the 2021 protests as Cuba had trouble getting much-needed ventilators and medication against covid under the embargo.

To briefly explain the embargo, many people think it means there’s US Navy ships stopping ships from porting in Cuba. This isn’t how it works; rather, while the terms change every couple years, any ship that ports in Cuba will not be allowed to port in the US for several years. As the US is a much bigger market than Cuba, this effectively means no ship will choose to unload their cargo in Cuba when the USA is right there and pays more. This effectively isolates Cuba and forces them to rely on themselves, in a world where no country can be entirely self-sufficient.

The embargo is very subtle in how it works, like we’ve come to expect after the days of overt CIA experimentation and meddling.

Sanctions come in

The ‘problem’ with Cuba was that they were too strong to simply invade. They also enjoyed good relations with the Soviet Union who had rebuilt its own economy after WW2 and was a strong contender against the ‘soft power’ of the United States. In 1961, only two years after the revolution, a group armed, funded and trained by the US tried to invade the Bay of Pigs in Cuba. They were swiftly destroyed on the beach. The CIA tried to assassinate Castro 600 times, with all attempts failing.

Like we’ve seen with Cuba, sometimes the country is too strong to influence from the ‘outside’. In this case, while we keep going with all we’ve been doing so far (the stories in the media, the reports by the State Department or ‘impartial’ NGOs), we also start probing actions against the target country.

We could start freezing their assets. Under the petrodollar, the system which essentially forces all oil transactions to happen with the US Dollar, countries need to own some of that currency and hold it in Western banks. Venezuelan funds — billions of dollars worth — were frozen by foreign banks after the color revolution attempt to put Juan Guaido in the place of the President was in full swing.

We could also enact unilateral sanctions. Our sanctions, you see, are democratic. When we prevented the DPRK (North Korea) from getting oil, we were only targeting the high officers and elite politicians, not the common people. Never mind the fact that if the DPRK is as dictatorial our media says, then the elites will simply hoard the dwindling oil supplies for themselves and not let the common people have any. Our sanctions are pure, they don’t kill people. They come from a good place.

In actuality, sanctions serve either of two purposes:

Make the legitimate, targeted government unpopular with the masses, like in the case of the embargo against Cuba. This discontent can then be exploited to fund a color revolution.

Get the targeted government to make concessions they would otherwise not agree to, like holding elections outside of the constitutional terms or letting a foreign-funded group operate within the country — like Belarus’ planted opposition Tsikhanouskaya, who used to call herself the ‘National leader of Belarus’ on Twitter, seemingly not caring that Belarusians might have an issue with that. The goal of sanctions against Belarus was to get her pardoned after she was convicted of incitement against the state.

We might also query the UN for intervention, and use the target country’s unwillingness to go along with the plans we impose on them as proof of their guilt. We might send equipment and weapons to the rebels and call it humanitarian or even ‘lethal aid’ (military equipment), if we manage to find a way to do so. The civil war in Syria started with foreign-backed groups, for example, who received weapons shipped through neighboring countries which they then brought into Syria.

These acts are always ‘democratic’. That’s the big buzzword in this day and age.

A system where the President is picked out of two candidates and independents have no chance of running; a system where the Supreme arbiters of law that set nationwide precedents are not elected and cannot be removed from their positions; a system where if constituents disapprove of their congressperson, they can’t do anything about it. That’s democracy.

And not only that, but it’s a system the entire world should emulate — even I, from my European country with multi party representation (more than 7) at all levels of government, should want that system for myself. I would be really dumb to not want that system.

Moving towards invasion

Slowly, eventually, regime change is brought up as a possibility. Our well-meaning sanctions didn’t work, our ‘moderate rebels’ didn’t work, so we realize only an invasion will actually work.

Regime change is brought up subtly at first, e.g. “Assad gassed his own people [and that’s why we need to bomb them and kill them too]”. “China would be free if it wasn’t for the communist party [implying a complete dismantlement of China’s society]”.

The consequences of an invasion are not invoked. Afghanistan has not been able to develop for 20 years — an entire generation — because of the invasion. Today, their literacy rate is only 37.3%. The 20 past years they could have used to build schools, educate their population, build a production base, and govern instead had to be spent fighting a civil war with foreign meddlers.

I’m aware the Talibans haven’t changed as much as some hoped, and I don’t expect them to fix the literacy rate any time soon. But it’s not our place to tell other countries how to run themselves (especially as the West created the Talibans). It’s not our place to meddle in their affairs. When we installed the friendly government in Afghanistan, we didn’t do it to help Afghans. As we’ve seen, opium production increased. Pedophilia continued unabetted. What would have helped Afghans would instead have been to not start the Taliban to fight against the Soviet-aligned socialist government in the 70s. Failing that, we should have promoted dialogue between the different factions, acting simply as mediators, to achieve a peaceful solution to the crisis.

The reason Afghanistan was so interesting, by the way, is that it’s very rich. The comprador government installed by the NATO coalition would have simply started selling the rights to exploit these resources to foreign companies like Glencore, BlackRock, BP and others.

Regardless, at the stage we’re justifying invasion, we’ll make up the evidence we need. I can count several examples of evidence fabricated to justify intervention off the top of my head. The Gulf of Tonkin incident, the Nayirah testimony, Iraqi WMDs, Syria ‘gas attack’, Uyghur ‘genocide’… the list goes on. The concept is not even new. The kingdom of Hawaii for example was annexed and became a State in the USA in 1895 after queen Liliuokalani was forced to abdicate. She wanted to change the constitution in a way that displeased business owners, who started protesting. With some US help, they eventually overthrew her. Then the US was able to come in to “help” with the situation.

Later, as public opinion shifts thanks to the continued effort of the State and media, the regime change rhetoric can be more overt. In the case of Iran for example, our media is essentially at the stage where they’re saying we need to outright remove the revolutionary government. The reason we want to remove Iran’s government is pretty simple, we want to bring back the monarchy under the Shah who used to let us own Iranian oil. Here is the Tony Blair institute (the man who pulled the UK into the invasion of Iraq) with an article titled The People of Iran Are Shouting for Regime Change – But Is the West Listening?

A very telling headline.

Speaking of Iran and Iraq, we supported Saddam — even helped him get elected — in his war against Iran in the 80s.

The situation was like this.

Just a year before 1980, the Islamic revolution succeeded in overthrowing the Shah, Iran’s supreme monarch, and establishing a Republic. The Shah was unpopular because he was backed by the UK and USA in a bid to control Iran’s vast oil reserves.

You see, following the turn of the 20th century, the Shah did not have absolute powers in Iran. Government was controlled by a Parliament and Prime Minister. At the same time, Iranian oil was controlled by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) since 1909.

In 1950, Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh decided that Iran should have sole ownership of its oil, which would make it more sovereign and independent. Under the terms signed years earlier, AIOC simply paid out royalties on barrels extracted but kept most of the profit for themselves. Most of this money also found itself in the Shah’s pockets directly.

Mossadegh set out to nationalize AIOC, and the Iranian Parliament voted yes on the proposition. Immediately, the UK and the US planned a coup. The military eventually captured Mossadegh in late 1953 and placed him in house arrest for the remainder of his life. Others were not so lucky, and were sentenced to the death penalty.

This is not controversial at all as in 2013, the US government formally acknowledged their involvement by releasing documents, proving what anti-imperialists had known for decades.

The coup ended with the Shah centralizing more power unto himself and Iranian oil was still owned by a foreign company. He then quickly aligned with the West and followed their own textbook: mass imprisonment and execution of dissidents until there was no one left to oppose him.

It rarely works out that way, and this context set the conditions for the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, which succeeded.

But the US had lost their ally and oil in Iran. Amid this crisis (for themselves), they were also worried about possible growing communist influence in Iran (which was one reason the Shah was brought back to rule over Iran, as the communist Tudeh party was steadily growing since the end of World War 2).

In 1980, Saddam Hussein — yes, the same one who would later be executed by the US Army — invaded Iran. The US had made him a very good deal: they would provide him with training, weapons and money if he went to war against Iran. Even better, he would be allowed to keep all oil fields he managed to conquer.

The war dragged on for 8 years. By the end of the decade, Saddam had not made any progress and eventually both countries signed a peace deal.

Kuwait was a US-aligned country. Thus, the US asked them to pressure Saddam into paying back the money they lent him for the war against Iran. On top of that, Kuwait was also siphoning Iraqi oil from their fields. When Saddam invaded Kuwait, the US turned against him. He’d made a deal with the devil and had to pay the price.

This lead to the first Gulf war in 1991, and if you were alive back then, you might remember the Nayirah testimony which I mentioned before. In 1990, a girl named Nayirah testified before the U.S. Congress that she had seen Iraqi soldiers rip babies out of incubators in Kuwaiti hospitals, urging them to invade Iraq and regime change Saddam over this transgression. It was later revealed, long after the US had sent boots on the ground in Kuwait and Iraq, that Nayirah was none other than the Kuwaiti Ambassador’s daughter, living in the US for years. The testimony had been entirely fabricated by a PR firm and given to the girl to read.

Saddam’s story eventually ended in 2006 when he was executed by the US Army following his capture in the Second Gulf war, also known as the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

After a process that may take years to come to fruition, popular opinion has been sufficiently moved that people will support war if we declared it. The job is not over yet, though. Until we actually act on this support, we keep up with the propaganda. Several circumstances might make it impossible to invade at the present time, and we wait for a better opportunity — for example, NATO still hasn’t joined the war in Ukraine, limiting themselves to sending mercenaries and weapons.

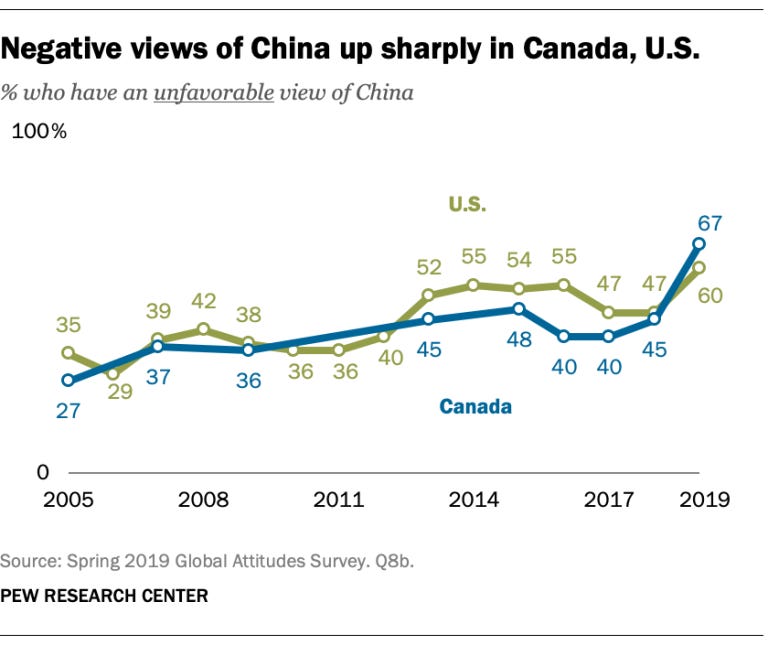

We see here for example the evolution of public opinion in regards to China. In 2019, the ‘Uyghur genocide’ was broken by the media (Buzzfeed, of all outlets). In this story, we saw the machine I described up until now move in real time. Suddenly, newspapers, TV, websites were all flooded with stories about the ‘genocide’, all day, every day. People whom we’d never heard of before were brought in as experts — Adrian Zenz, to name just one; a man who does not even speak a word of Chinese.

Organizations were suddenly becoming very active and important. The World Uyghur Congress, a very serious-sounding NGO, is actually an NED Front operating out of Germany (from the same town the CIA-owned Radio Free Europe operates). From their official website, they declare themselves to be the sole legitimate representative of all Uyghurs — presumably not having asked Uyghurs in Xinjiang what they thought about that.

The WUC also has ties to the Grey Wolves, a fascist paramilitary group in Turkey, through the father of their founder, Isa Yusuf Alptekin.

Documents came out from NGOs to further legitimize the media reporting. This is how a report from the very professional-sounding China Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) came to exist. They claimed ‘up to 1.3 million’ Uyghurs were imprisoned in camps. What they didn’t say was how they got this number: they interviewed a total of 10 people from rural Xinjiang and asked them to estimate how many people might have been taken away. They then extrapolated the guesstimates they got and arrived at the 1.3 million figure.

Sanctions were enacted against China — Xinjiang cotton for example had trouble finding buyers after Western companies were pressured into boycotting it. Instead of helping fight against the purported genocide, this act actually made life more difficult for the people of Xinjiang who depend on this trade for their livelihood (as we all do depend on our skills to make a livelihood).

Any attempt China made to defend itself was met with more suspicion. They invited a UN delegation which was blocked by the US. The delegation eventually made it there, but three years later. The Arab League also visited Xinjiang and actually commended China on their policies — aimed at reducing terrorism through education and social integration, not through bombing like we tend to do in the West.

But it fell on deaf ears. The sentiment at the time was that the Arab League wanted better relations with China and so they lied and said everything was fine.

Everything the target country does to prove its innocence is a lie. Only we profess the truth.

We suddenly stopped hearing about the ‘genocide’ as the world moved on to the war in Ukraine and now the October 7 operation in Palestine. These last two events were not controlled by Washington, and so they had to take precedence over the ‘genocide’. But it’s not over yet; they’ll find something else to pin on China eventually, and when they do, they’ll want you to remember all they’ve said about China in the past. They’ll want you to remember Tian’anmen (another mostly fabricated event), they’ll want you to remember the Uyghur ‘genocide’. They’ll want you to remember Tibet (for which they try to find stories, but they don’t tend to stick for very long).

All so that when they make up more ludicrous stories about China, you’ll think they’re true, because you’ve been conditioned to believe more and more outrageous stories with time.

When we finally declare war on China (if the NATO bloc ever gets to find a way to win that war), you’ll do the legwork of justifying this invasion yourself. We hope you’ll have been properly subdued by then and will happily cheer for the bombs. And if we install a US comprador government in China, we hope you won’t ask too many questions as it starts privatizing everything, reversing social welfare policies, jailing opponents, plummeting quality of life, destroying jobs and houses… and will just happily accept it as the right legitimate government — because it’s Western-backed.

This is the basic playbook that we’ve seen time and time again. It hasn’t changed too much since the early 20th century; we change the arguments and we try to be more covert about it, using shell companies and organizations to obfuscate where the funding comes from and who the actual instigators are, but the mechanism isn’t very different from what we saw in Cuba, Chile (Pinochet dictatorship) or Iran back in the day.

What happens if the operation succeeds

If the operation succeeds, a pro-US dictator is ‘elected’ or simply seizes power, like Juan Guaido tried to do for over a year in Venezuela and like Jeanine Añez briefly did in Bolivia.

From there, neoliberal policies begin. Under the guise of “fixing the economy”, the new comprador ‘President’ sets out to cut public spending and get rid of unprofitable (but vital) state-owned services or businesses. Much like the new President of Argentina Javier Milei announced, entire departments get closed down, and the economy is privatized — state-owned assets are sold for pennies on the dollar to private companies who will then turn a vital service, such as water or energy, into a profitable venture.

IMF loans will be taken. The IMF (International Monetary Fund) is an imperialist organization, which came about as part of the Bretton Woods agreements which propelled the United States as the world’s superpower. IMF loans are predatory and come with strings attached; the interest rate is at least 7-14% (which even private banks don’t do), require to be paid back in precise amounts and timeframes, and have penalty clauses in case the country can’t pay back the loan — most commonly the seizure of assets. The money is also earmarked for specific, valuable uses. For example, you cannot get an IMF loan (as a country) for road infrastructure or public spending — two vital services in the modern day. You can only take them to build mines, industry, agriculture — things that make money and that can be easily seized.

When you eventually can’t pay back the predatory interest rates, they will seize the asset and sell it off to our own capitalists. And you will be forced to take another loan to pay off the first one, but at even worse rates. This is called ‘debt restructuring’.

The people that agree to sign off on this loan know this of course, and might not even need it. But as a US-backed regime, they are obligated to follow this scheme. If they don’t, they know they will be replaced or will lose the cozy kickbacks they get from following the instructions.

The President or dictator will become a great friend of the country, like the house of Saud (a country in which women were not allowed to drive prior to 2018), Augusto Pinochet, Jair Bolsonaro or Benjamin Nethanyahu. They will be invited to diplomatic summits, ties will be strengthened between the US and their country, and all will look swell. Meanwhile, at home, they commit crimes against humanity on a daily basis.

This is when actual, real crises happen. People displaced from their land to make way for industry, or protestors shot and arrested by the police. Dissidents tortured and jailed for years without trial for writing against the dictatorial government.

But it’s rarely talked about. At least not as much as the fake protests were before the coup.

The media might, at times, publish stories that paint the dictator in a bad light and bring attention to the humanitarian crises. For example, Human Rights Watch (who likes to go against the Global South but rarely talks about all the humanitarian violations happening in the US) did talk about infringements on the rights of Indigenous people under Bolsonaro once.

This is known as a limited hangout; real, factual information is released by/to the media once in a while, between the fake information. The point is to make you trust the fake information when you come across it, because you believe the media to be trustworthy when they do actual reporting.

It also helps restart the process of regime change quickly if the dictator we installed suddenly decides he doesn’t want to play by our rules anymore or we find another one to support.

“To be an enemy of America can be dangerous, but to be a friend is fatal” said noted war criminal Henry Kissinger, who was the architect behind the bombing campaign of Laos during the invasion of Vietnam.

What about you though?

When I explain this playbook to people, there’s usually two reactions: either they don’t believe it, or they think they are isolated events and not indicative of generalized policy in the Global North. Usually in Europe, we think this only concerns the USA and our own hands are clean (however, we are a big US ally and we also carry out our own imperialism — France in West Africa, for example, and the UK in Iran as we saw previously).

What about you? What do you think? I would love to read your thoughts in the comments below.

You don’t have to believe me from the start. Usually, people have trouble believing this is how the world truly runs because it puts everything they’ve been taught into question. I also went through this phase early on when I started learning about all this and putting the pieces together.

But it’s okay. You don’t have to admit you were wrong, because you were not really wrong. You were misled on purpose.

It does get easier as time goes on. Once you know what to look for, you’ll start to see the signs. Next time you read a story about an ‘enemy’ country, I hope you’ll think back to this article and think about which step the story you’re reading is at.

Finally, let’s summarize

I know this article was a lot to read. I hope you still managed to follow through and not get lost in the many historical examples.

To help out, here’s the step-by-step process summarized:

A strategic country is selected as a target.

Stories start being fed to the media about human rights abuses or just concerning developments (lack of democracy, dwindling economy, etc).

To help lay the basis, the government may make official reports the media can then use. They might also use humanitarian NGOs (Amnesty, HRW…) or outright CIA outfits (World Uyghur Congress, Radio Free Europe…).

Stories start coming out more and more often. The volume of coverage regarding the target country becomes much bigger than before the campaign.

At the same time, groups and individuals in the target country, that have been funded by the imperialist country, are being put in the spotlight. They have been groomed for years, laying somewhat dormant until it’s time to activate them.

Stories about these groups call them champions of democracy, freedom fighters, etc. A clear limit is drawn: they are good people, and the government that’s preventing them from achieving their policies are the bad guys. This is the basis of a color revolution.

Slowly, public opinion starts to shift. We don’t necessarily act on this opinion yet though, we plant the seeds to make later consent easier. Each seed makes the next one easier to plant and grow.

The imperialist country continues the campaign but also starts small, probing actions to see what it can get away with. It might enact sanctions or query the UN for intervention. It will also call these acts “moral” and underline that they are meant to sanction the country until it becomes a democracy again, further digging the good vs. evil line.

Meanwhile, everything the target country does to prove its innocence and lawful conduct is not published or gets blocked (e.g. request for a UN delegation visit). Their point of view is never printed in the media or if it is, only when they can spin it in a good way.

Slowly, regime change is brought up. Subconsciously at first (e.g. “China would be free if it wasn’t for the communist party”, which implies destroying it and the system it built). Later, it can be more overt (e.g. Iran).

Finally, consent has been manufactured and public opinion has completely shifted on the target country. People come to see invasion as the only solution, and they will happily support it once it happens. It may not happen for several years though, as material reasons might not make invasion possible. Sometimes, a color revolution (which is mostly carried by nationals of the country in question but funded and trained by the imperialist country) is the best thing we can do.

If the operation succeeds:

If the operation succeeds, a pro-US dictator will be ‘elected’ or seize power. The election will be called fair and democratic, as was the case in Ukraine 2014. This president will be paraded around in the West and become a media figure that everyone comes to know. This is what happened to Zelensky, but also to Pinochet in his time and Juan Guaido.

Inside the country, everything gets privatized and sold to US and European companies under the directives of the dictator. This is rarely talked about or if it is, it’s presented as banal — e.g., “Ford to open factory in Argentina”. Quality of life plummets, actual humanitarian crises start, etc.

The media still publishes stories on the country, but always in a good light, and not as many as during the operation. They might sometimes call to unrest in the country but always as a distant, abstract phenomenon.

As long as the dictator plays by our rules, the country keeps being talked about positively. As soon as he starts to become too independent, we will use the chaotic post-coup situation to repeat the process with a new President.

All of my writing is freely accessible and made possible by the generosity of readers like you. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting me. I’m on Ko-fi, Patreon, Liberapay.

Bitcoin (BTC SegWit network) - bc1qcdla40c3ptyrejvx0lvrenszy3kqsvq9e2yryh

Ethereum (Ethereum network) - 0xd982B96B4Ff31917d72E399460904e6F8a42f812

Litecoin (Litecoin network) - LPvx9z9JEcDvu5XLHnWreYp1En6ueuWxca

Upgrade your Substack subscription for $5/month or $50/year:

Share this essay:

We sanctioned Japan during WWII, they bombed Pearl Harbor a legitimate military target. The US then decided to join the war and we bombed civilians indiscriminately. Oh, the US funded Hitler. Then the US dropped 2 atomic bombs on civilians. Japan has been a US vassal state ever since. It was bombed into submission. The US is currently causing issues in Georgia, Moldova, and Romania.

Nit: Silicon isn’t rare. It’s one of the most abundant elements.