Retrofitting capitalism onto the past: how ideas evolve and change

Capitalism is not a constant of human history, but we still treat it like one.

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like and restack! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

Recently, I wrote about how a certain video game that claimed to simulate the feudal mode of production ended up creating its own ahistorical system, constrained by the game mechanics that could never properly simulate feudalism without cutting corners.

This led to a broader discussion with some readers about how assumptions regarding history are pervasive not only in the genre, but even across different forms of fiction, and even in non-fiction!

This is indeed nothing new. As far back as the Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith imagined trade before his time through the barter system, which you probably learned about in school: before money existed, he figured, people bartered with each other on a case-by-case basis. The fisherman might want bread one day, and goes to the baker to exchange some of his fresh catch. But the baker would rather have firewood, which the fisherman doesn’t own. The fisherman goes to the woodcutter, and exchanges his fish for some firewood. He then brings that wood back to the baker, and exchanges that for his loaves of bread.

If that seems far-fetched to you, you’re not alone. We know from anthropological and archeological studies that this is not how human economies ever operated, at least not on a systematic basis. Of course sharing and exchange existed back then and still exists today, but it did not form the basis of a systematic, long-standing economy or trade system: it would have been a very unwieldy system to keep up with at a societal level. This complicated system, Smith said, is how money came to exist — as an abstraction of the barter system. Instead of exchanging 5 fish for 3 loaves of bread, or 4 fish for 10 bundles of wood, the fisherman could sell (or exchange) his 5 fish for 3 coins, and use those coins to buy the loaves of bread directly.

Smith may be forgiven for this assumption as was the first to set out and explain how money works in capitalist society, namely Britain. In explaining what money was, he found himself having to explain why money came to be in the first place: why did it exist? How did he come to have shillings and pence in his pocket?

In Debt: The First 5000 Years, author David Graeber directly challenges Smith’s assumption. Pouring through historical and current-day examples, he methodically shows how the first human societies organized their economy. The first systematic form of trade, according to him, was not barter but debt. Debt came in many forms, and is simply defined as payment that will happen later. Some societies, for example, put goods in common and allowed anyone to take from them (usually not from a common stockpile like in sim games, but from whoever was holding onto the item at that time), with women often serving as record-keepers or accountants on the understanding that whatever you took or borrowed, you would eventually repay back with something else. Goods and items had a very specific value, and while repayment often happened in various ways (either with other items or with services rendered), the value of what one had to repay for what they took was kept very precisely. This directly challenges two of Smith’s claims: that private property had always existed, and that people had to trade things of subjective value on the spot to get anything.

We tend to think of ancient peoples as dumber than us, living in more primitive times. But our brain structure has changed very little since the first Homo Sapiens some 300,000 years ago! We have the same hands, the same brain, the same eyes and mouth. If something in history seems needlessly complicated or convoluted, then it generally means that it’s an ahistorical fact created later down the line.

The first historical societies in fact (history being defined as happening after the invention of writing), such as Ancient Mesopotamia, show that economies were already fairly well-developed. Money was there first developed as an accounting tool, a placeholder to nominally estimate the value of every good when it came down to make laws and, of course, tax the king’s subjects.

When it came time to collect tax in Ancient Mesopotamia, harvest was weighed and taxed according to an anchor value: a sheqel, for example, was a unit of weight corresponding to about 11 grams of barley (they also used the mina and talent, corresponding to heavier weights). While the sheqel eventually became minted as coins, it first existed solely as a number on paper (or rather, clay tablets)!

The purpose of the sheqel, mina and talent was simply to make accounting easier: rather than counting individual grains of wheat or barley and inscribing that amount on a tablet, tax collectors could weigh the harvest and determine how much of that mass should be paid to the king as a tax in kind (meaning how many grams of barley from the harvest would go to the king’s personal stockpile). It also allowed more complex taxes or exchange rates to be calculated and paid, for example by measuring the size of a field and determining a taxed portion not equal to a fraction of the size of that field (e.g. 1 meter squared of harvest), but in weight — requiring two units of measures instead of just one (e.g. if you had a 10 acre field, you would pay 10 taler of barley for it). It allowed for contracts to be made, and for laws to back those contracts.

It makes sense that barley (or grain in general) was used as the anchor value rather than gold or silver, which we associate with the gold standard: back then, and for most of human history, labor was mostly expanded towards producing food. Enslaved people, which formed the bulk of labor, were mostly bought or captured to work in the fields through which their work fed their owner. Food formed the basis of society even as precious materials were mined (albeit in limited quantities until the Industrial Revolution).

Coins eventually did come to be circulated in Ancient Mesopotamia, but some 1,500 years after the first historical records emerged from that region. To give some perspective on that timespan, well, just think of how old you are today and how many generations you would have to go back to find an ancestor living in the year 524. For that many generations, trade worked just fine without the barter system and without any coins to back it up.

Explaining the origins of money was not the core of Smith’s theory, though you might not know that from reading his proponents in the modern-day. When it came time for him to propose an explanation as to how money came to exist, he drew back on his own experiences and context: a nascent capitalism in Britain, which had already started colonizing the world and using the steam machine. The bourgeoisie was in the cutthroat process of primitive accumulation, reproducing capital through productive yields inconcevable of in previous times. In this context, Smith’s views of ancient societies were a reflection of his own: societies in which private property was sacred and widespread, where everything came with a price tag and in which everyone had a very specialized job (we saw in the previous article — link at the very top — that this wasn’t entirely true).

Thus Smith retrofitted capitalism onto the past, and mashed that past in his image until it fit into his mold.

He didn’t do this on purpose to try and praise capitalism. Most people don’t; most earnestly think that the way society is structured today is the way it was structured in the past, and has always been. It makes sense to us to think this way, because it’s familiar. It’s simply sensible.

But perhaps this is what makes this projection so dangerous. We are so accustomed to the way our society works, and to seeing it represented subconsciously in the media, that we don’t question how fiction is depicted. In fact, I believe this also leads to capitalist realism: the idea that capitalism is constant, immutable, has always existed and therefore will always exist. It keeps us from engaging fully critically with our surroundings and criticizing the system, thinking of it as “not perfect, but the best we’ve got” instead of asking if, much like the earliest forms of taxations were not perfect, we could find something better, more able to answer our needs.

This is pervasive and becomes completely subconscious. What you read (whether fiction or not), what you are taught in school (and the way you are taught it), what you are not taught… all of this contributes to shaping your own ideas. I’m reminded at this time of French activist and lecturer Franck Lepage, who liked to explain in seminars that voting for class president throughout your formative years, for example, is primarily a way for the system to be ingrained onto young minds, so that they will not question voting as adults.

He also explained that the most-used word in management textbooks in the 60s was the word ‘hierarchy’ (and respecting it), while the most-used word in those same textbooks in the 90s was… ‘project’. Over time, a shift happened towards projects, signalling perhaps more autonomy in the workplace, but also more responsibilities and thus labor to perform. This even bled in daily life, with people often asking “what are your projects this summer?” and other similar questions, implying that you need a project to be somebody, that if you don’t plan your next big adventure, if you don’t have things happening on the side and are actively seeking them out, then you might as well not even exist.

This is a very modern idea! But it doesn’t seem like it, does it? Yet, for most of human history, people were content to simply be alive — it’s not like there were many creative outlets for most of the population, who needed to fend for themselves to survive in harsh class societies.

As such, when we come across very modern ideas transposed into older settings, we are all but encouraged to ignore the contradiction, to gloss over them and take them for granted. “Of course the main character would be against slavery in this tyrannical medieval fantasy setting, slavery is morally bad!” is essentially the thought process.

And yes, slavery is bad, but it was also the norm for most of human history, and yet slave owners didn’t seem to think too much of it. Why didn’t they? We’ll come back to that in just a minute.

Some of those ideas that came out of the discussion I mentioned in the opening sentence to this article were, for example, the idea of town guards in RPG games. They’ve been a fixture and cliché of the genre as far back as RPGs have existed in video game form, and perhaps even earlier in other forms of media (though TV Tropes mainly places the “City Guards” trope in video games).

In a way, they are a projection of the police, under whose authority we constantly live, whether we are interacting with them at this moment or not. Historically, cities did not have guards in armor patrolling the streets and stopping crime. That would have been very expensive to maintain, doubly so if that was the only job they did, and was simply not the best use of the meager resources available to a town or village. Interestingly, TV Tropes itself falls for this trope, writing that:

[City Guards] are rather ubiquitous in Real Life. In many places around the world they tend to be known as "the police".

Likewise, I’ve always found the concept of the guild hall or bounty board in RPGs to be very strange. As if people who couldn’t read or write would pay someone to put up a request on the village board to be fulfilled by a stranger in exchange for money (what wealth would a serf possibly own, and what foreigners would possibly visit a rural village!) In reality, people would simply ask their neighbors for a favor and perhaps incur some informal debt as a result which they would repay in the future.

In that way, the guild hall — most common in Japanese RPGs — shows your hero party being subject to a hierarchical, highly-organized institution owns a monopoly on taking care of people’s requests. Yet they are often represented as a benevolent institution that achieved monopoly not through back-handed deals and a lack of conscience, but through hard work — thereby earning their place as a rightful monopoly. Does that remind you of the Zaibatsus?

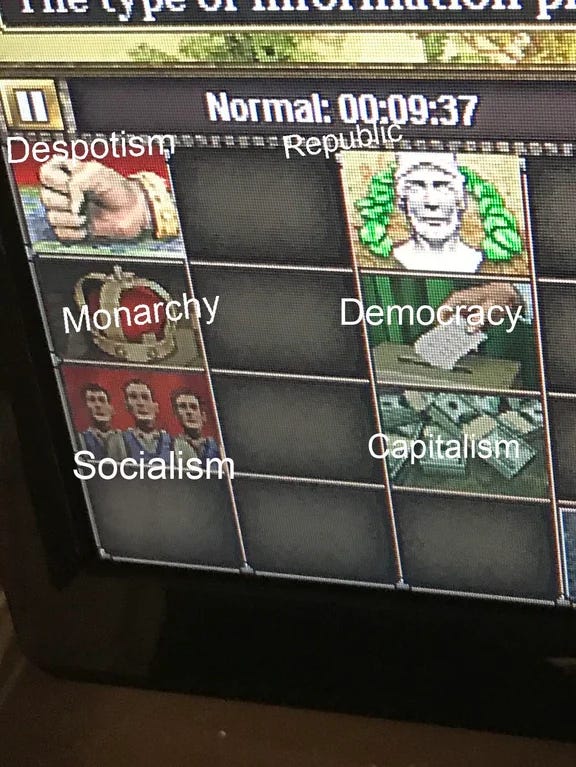

Strategy games like to provide the player with a tech tree for the player to work their way through, thereby tempering and controlling progression throughout a timed game. Some of these tech advancements concern politics, offering different bonuses depending on the game. Often, possibly due to a lack of political education on the game designers’ part, civic technologies follow a very liberal reading of history: in Rise of Nations for example, capitalism is part of the “consensus” government form, also called democracy (what is democratic about obeying the every whim of an employer, the game does not say). Capitalism follows from the Republic in ancient times —despite that form of government being very limited in spread in this historical period — which is followed by the “Democracy” government before Capitalism.

According to Rise of Nations, Democracy and Capitalism are one and the same, and you can’t have one without the other.

Meanwhile, socialism is part of the “totalitarian” branch, following despotism and monarchy government forms in previous ages, despite that socialism can not and has never followed monarchy directly!

(It’s also unintentionally funny that the tech with the dollar bills is depicted alongside democracy, while the one with people in it isn’t.)

Ideology is created and is reinforced so that it can self-reproduce without any effort required. I also see this in Russian games; even though socialism was harshly uprooted from Russia in 1991, they still have a certain way of portraying fiction that is to some extent Marxist: focusing on class struggles, issues of labor, and taking a more historical materialist view of technology progression. Chinese developers are also starting to breach into the international market through Steam, and many of their games have some of those themes imbued in them as well.

In examples outside of games, I’m reminded of how romanticism for the medieval era was at its peak during Victorian times, which coincided with the Second Industrial Revolution and the final nail in the coffin for feudalism. A growing bourgeois class, which corresponded to a growing proletariat class (as the bourgeoisie needs people to employ after all), led to a revival of the medieval theme. Not solely through the angle of looking fondly at the good old times — because the bourgeoisie were not feudal lords, and in fact were at odds with them — but through the exaltation of certain values.

It’s no secret the Victorians invented many aspects of feudalism such as chivalry (the duty to a figure of authority), honor, sacrifice, etc. and even reinvented how feudalism itself actually worked, both as a way to critique their ruling predecessors and elevate themselves to a more benevolent role than what they actually were: an exploiting class just like the nobles.

I’m reminded for example of Ivanhoe, a novel written in 1819 which deals with the topics of duty and honor. Edmund Leighton’s The Accolade portrays the same themes through the visual medium, though it was painted at the very far end of the Victorian era in 1901.

At the time, Britain was engaged in very violent and barbaric colonialism. Paintings embodying a benevolent Britain looking down at its subjects with motherly instinct and wanting what’s best for them was certainly in the interest of the crown and these colonialist ventures.

Thankfully, we have almost entirely debunked all of the Victorians’ misconceptions about feudalism — perhaps because at this time, the bourgeoisie having achieved hegemony as the dominant class, doesn’t need these ideas to be propagated anymore.

A very obvious counter to all of the above is that people simply look to what is most familiar to them for inspiration, and that authors aren’t willfully imbuing their creations with their ideology. And if they’re not trying to be deceitful or ideologues, then what’s the harm?

But this is exactly the pervasiveness of ideology, though that’s a full discussion for another article. Ideology permeates us and the world around us. This is best explained by the base and superstructure model:

Things start at the base: at the tangible world. We labor for our survival through making tools, producing food, etc. and even when our labor isn’t directly related to producing those, it is necessary to keep society running, and affords us money that lets us purchase the food and clothes we need to survive. Accordingly, the base is represented by our means of production as well as our system of production.

In turn, this base shapes and keeps a certain superstructure alive. The superstructure is represented by the broader society, such as art, culture, laws, media, etc.

But in a dialectical relationship (we’ll come back to that word in a minute), the superstructure also shapes the base, which then shapes the superstructure, which shapes the base again in a continuous spiral.

We live in capitalism, that is our base. Capitalism needs certain institutions to be alive. It needs to legally recognize private property so that the owner of such property can employ people to work on it. This starts to form a superstructure. This relationship might be represented as an allegory in a painting, here in Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals (picture below). The mural depicts the relationship between man and machine in the factories, where they start to form one and the same — a critique of capitalism, but also a standing ovation to the workers who toil to make industry happen (notably absent from the mural is any factory owner or capitalist, though it was commissioned by one). This mural may have inspired workers to form a union and strike, thereby changing the base, the relations of production, ever so slightly. There we see how the base shapes the superstructure and back.

But the base also maintains the superstructure and vice versa.

You were likely brought up to respect the law, and that is probably very important to you as an adult (to the point that this translates to the physical feeling of guilt when you seriously think about breaking the law). Your parents brought you up like that because it was the right thing to do, and it was normal for them to bring up a child as a well-adjusted member of society.

But it’s also true that obeying the law, not making any noise, etc. helps the established state of things. It helps your boss when you don’t report his wage violations. It helps your landlord when you don’t bother them about the leaky faucet. It helps the courts when you accept your sentence solemnly (whether you’re actually the culprit or not). It benefits the established system when you don’t steal, when you don’t question private property, when you just submit to being a worker and happily accept that role, believing it not only to be natural, but even in your best interest!

Your parents, through bringing you up as an exemplary citizen (and as much as they believed that themselves) were perpetuating the superstructure: the laws, politics, education, culture, etc. of their and your society.

I often come back to a certain quote by Karl Marx: in every epoch, the ruling ideas are the ideas of the ruling class. What benefits them the most is what they will push to have become the norm. Then, these ideas become accepted and passed down to the new generation of workers, in a form of work that is still unrecognized: the reproduction of labor.

And doesn’t it help your boss to make you believe that town guards have always existed — that the police is a constant through the ages — so that you start to believe capitalism is making the best of what we’ve got, which is a shitty situation that we can improve a little bit (in the interest of the bourgeoisie, of course), but not surpass in favor of something entirely better?

In other words, accept your job, don’t ask too many questions, and just be glad you’re not a serf. That’s as good as it’s gonna get, and that’s what modern ideas transposed to the past often ultimately end up reinforcing. The only time I find the past to be accurately represented in fiction, actually, is when it also reinforces capitalism: when it shows why capitalism is qualitatively better, and that if you’re having a bad time right now, you would be having an even worse time back in the past.

I also challenge that assertion though (call it my contrarian nature). Economist Jason Hickel claimed in a 2023 study that extreme poverty (poverty so dire one cannot fulfill their basic survival needs of clothing, shelter or food) by and large didn’t exist before capitalism and outside of irregular events such as floods or disease, though it’s not like we’re doing much better on these issues today. Subsistence in the past was assured, even if it was a meager and difficult life. The slave was an investment, and so he was assured an existence. The serf was directly enriching his lord through his work, and so he was assured an existence.

The proletariat, on the other hand, was firstly used for unqualified labor — pulling a lever on a machine, or turning a wrench on a screw. While the proletariat as a class is required for the bourgeoisie to have someone to employ and make them money, it doesn’t need any specific prole to do that. If, forgive me, you died at work tomorrow, your boss will have you replaced by the end of the week. The proletariat is not assured an existence, and capitalism forced millions who relied on subsistence farming into large towns and factories where their only mean of survival was not through working the land themselves (which had been grabbed and enclosed by the bourgeoisie), but through finding employment day after day.

The base and superstructure model however doesn’t aim to explain why things change. The medieval epoch was popular to the Victorian bourgeoisie, but that fame did not carry to the modern day. Today, the medieval fantasy genre is more popular than the hard historical medieval genre, and focuses on entirely different themes. Whereas the Victorians focused on ideals of duty, honor and loyalty, the medieval fantasy genre often focuses on grand adventures, the role of the individual (and the unlocking of their potential), tolerance, an innate good versus evil, the mystic nature of the world through magic, etc. — all modern sensibilities that are at odds with the Victorian conception of the genre.

We can see from this one example that ideas do change, that they’re not a constant throughout history. If we’re able to change the way we relate to fiction, then can’t we also change the way we relate to society?

In other words, when we say “there’s always going to be a need for the police, because people are always going to commit crime”, are we making a truthful statement, or are we projecting our modern acquired sensibilities onto the past?

Why do ideas change? To understand that, we can look to the dialectic. the Ancient Greeks invented the concept; to them, dialectics took form in a dialogue between two people with opposite ideas. By debating their two ideas, they would eventually come to understand a third idea which did not exist before. As an example:

I think we don’t need the police ; you think we need the police → we debate our ideas, and eventually reach a third, new idea: perhaps that some police might be (un)necessary.

The idea that “perhaps some police might be necessary and some might not” did not exist before in our shared context, as neither of us had put forward that specific idea. It was born out of our two opposite opinions.

You might also know this as the Socratic method, though he was far from the only one to use the dialectic.

This was an incomplete dialectic however, but it explains the general process of it: we take two things and process them somehow and a third, new thing comes out of it. It was Hegel that first did the most to develop the dialectic. His model of dialectics was that it was the driver of change in the universe (not just between humans, but between all things that exist) obeying to certain rules that he was able to isolate. But he could not yet explain why dialectics happened in the first place. He understood how ideas changed, but did not understand how they came to be in the first place.

A side note to help potentially confused readers: read dialectics as being very literal. When I say change happens, I mean any kind of change that can be observed. For example, blow a balloon with air. The balloon goes from being flat, to being full, to popping. Change happened: the balloon existed, and now it does not. It has changed from being full to now existing in pieces. Dialectics don’t just apply to society and human relations, but to everything that exists around us.

In Hegel’s model, the end of slavery happened because abolitionists started realizing that slavery was bad, that it was cruel to own another human being as property. With that idea in mind, they fought to free the slaves. Eventually, their ideas propagated and convinced more people to become abolitionists too, and once they reached the right people, laws were passed to abolish slavery.

In the Hegelian model of dialectics, ideas happen first and make material change happen in the second phase (the passing of laws, the end of slavery, etc).

But where do ideas come from? How did the first abolitionists start to think slavery was bad?

Hegel didn’t have the tools yet to answer that question and blamed it on God, which you may see as a a stand-in for “we may never know”. We had to wait until Marx to put dialectics “right side-up” and find the true cause of change, that was able to explain where ideas come from.

It’s no coincidence that the first (successful) abolitionists lived in a time where they could actually move on from slavery and propose something to replace their free, but inefficient, labor. It’s also no coincidence that some abolitionists existed not to altruistically emancipate their fellow human being, but to better control him through the colonial system (I recommend Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism to read how pervasive this outlook was at least in regards to Africa).

When James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny to make cotton processing more efficient, he hoped that this would lead to plantation owners needing fewer enslaved people, thereby reducing the demand and supply, as bleak as that sounds.

The opposite happened: as plantation owners could more easily process their vast cotton harvest, they became wealthier and could afford to buy more enslaved people, and they did.

Making slavery obsolete required that another form of labour be able to replace it, which was the material basis. But this basis didn’t exist yet in Hargreaves’ time — at least in the United States.

Slavery was eventually mostly abolished in the United States with the Civil War some 100 years after Hargreaves’ invention. The North, which did not rely as much on slavery for production, was at that time much more productive than the South. But the slave owners were not ready to abandon their privilege (this is another character of dialectics: it only describes how change happens, it doesn’t make it happen automatically), and a war erupted to bring them in line.

The war was not fought for humanitarian concerns over the slaves, however. After all, African slaves were still exploited through the cropshare system after the war, and lived under segregation until 1964. Rather, it was fought because the South was so unproductive in the age of the steam machine that the US could not move on with its grand plans with such a weight dragging behind it.

This is what led to the Reconstruction after the war as well, which was passed off as a concern to help the South economically catch up. In reality, the North (or rather the reunited USA) needed to become an economic powerhouse if it wanted to economically develop, which necessitated, in the 19th century, to colonize other people. It also needed to make sure the South was defanged so that slave owners would not rise up again to try and reclaim their privilege; to do that, the North developed a proletariat in the South to replace slavery.

Britain was still the major colonial power in the world back then, and the US was coming in very late into the process of exploiting labor and resources in foreign land. After the reconstruction was complete, the US swiftly colonized Hawaii in 1893 — a topic for another article, but an annexation that allowed them to have a base of operations in the Pacific. They then took Cuba in a war against Spain to grow their own sugar instead of relying on imports. Cuba was ceded along with the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico in 1898. This paved the way for further expansion throughout the 20th century.

To give credibility to this reading of history, this was far from a unique event. World War I was fought to redraw colonial borders, and it’s no surprise it opposed early colonizers (France and Britain) against latecomers (Germany, Italy and Austro-Hungary).

But let’s get back to philosophy. There is a very simple way to prove that materialism (the outlook that material conditions effect change on our ideas) is correct over idealism (the outlook that ideas effect material change): the material world can exist without human consciousness, but human consciousness can’t exist without the material world.

The latter, however, was exactly how idealists before Hegel defended their philosophy. They claimed that since you could not experience the world without consciousness, then for all intents and purposes it didn’t exist outside of your own subjective experience of it. If this sounds silly, believe me, it is. But they defended themselves on that point too: their philosophy requires so many hoops to jump through to believe it that it must be right, right?

Comparatively, materialism is strikingly simple: the world around me exists, therefore it’s real. It’s not very sexy, is it? But to believe otherwise requires to ignore the reality in front of one’s very eyes!

Idealists defend themselves from this by saying that everything is subjective. What is real to me is not real to you. If you are colorblind for example, you may see the leaves on a tree as blue, but I see them as green. Yet, there is an objective reality to this tree: we can measure the pigmentation of the leaves and understand why they fall on the green part of the color spectrum. We may not always be able to know this objective reality at any given time, but it exists regardless of what we perceive it to be.

To believe idealists is to believe that the sun is a yellow disc with a crown of rays surrounding it!

… We took a detour, didn’t we?

There are 3 takeaways to understanding fiction:

Every creative output exists in a context from which it cannot be dissociated, no matter how hard one tries (both for the author and the reader).

This context is informed by the conditions prevalent at the time which it was made or experienced, whether subconsciously or willfully.

Conditions change and are not constant, therefore fiction changes what it portrays and how through time, even if two works might seem similar on the surface.

This is also what makes it difficult sometimes to critique fiction. Often, authors and fans defend themselves by saying they did not intend for a certain reading of their story to be made, that if you read “this much into it”, then you simply overlooked the intended themes which were made quite clear.

Starship Troopers, for example, is considered to be a good satire of fascism, and people who don’t get the satire are mocked for not seeing the obvious themes. But as writer Roderic Day put it:

I think PV [Paul Verhoeven] is very earnest, and I like what he was trying to do, but he failed. Objectively he failed. And to the extent he had some ability to stop this and didn't, he's in fact complicit. One can't say their film was clever critique then profit off of completely unironic merch that unambiguously glorifies the supposed target (source).

This is the sort of portrayal that led François Truffaut to declare many decades earlier that “there are no anti-war films”. No matter how much directors try to criticize and denounce war, they end up making it seem cool. It’s the same way with mafia movies: by portraying mafiosos, even if they’re deeply flawed or downright evil characters, their good traits inevitably come out and we start identifying with them. They do things for a reason. In turn, either through conscious or subconscious bias, directors soften the bad traits of their characters.

The Godfather, for example, is famous for reifying the mafia to something more than a loose group of dog-eat-dog hardened criminals, turning it into a family structure with values and codes. The aesthetic in the movie was invented for it, and it was after the movie came out that mafiosos started acting like the Godfather characters did. The mafia has always only ever been a den of human trafficking, drug peddling and random abject violence — thus the name of organized crime. The idea of being a large extended family, of having moral codes against civilians, or even dressing sharply? It all came from the movie, and for the purposes of telling a touching story. After all, if Michael had been shot with a crossbow and left to freeze on a meat hook for the entire movie so that some Made Man could have taken his place as capo, there wouldn’t have been much of a movie, would there?

All of my writing is freely accessible and made possible by the generosity of readers like you. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting me. I’m on Ko-fi, Patreon, Liberapay.

Bitcoin (BTC SegWit network) - bc1qcdla40c3ptyrejvx0lvrenszy3kqsvq9e2yryh

Ethereum (Ethereum network) - 0xd982B96B4Ff31917d72E399460904e6F8a42f812

Litecoin (Litecoin network) - LPvx9z9JEcDvu5XLHnWreYp1En6ueuWxca

Upgrade your Substack subscription for $5/month or $50/year:

Share this essay:

Good essay all around. While the current world system we live in is dominated by the capitalism, and it may seem like it has been around forever it is important to know that it is relatively recent mode of production. The 'Long 20th Century' is a book I read earlier this year that may interest you. In that book, Italian marxist Giovanni Arrighi traces the origins of the modern capitalist system to the medieval Italian city states. Fidel Castro also makes a similar case in his 1991 interview in Guadalajara and points out to how new the concept of socialism is in comparison.

I generally don't watch war movies these days, but you nailed it with the "there are no anti-war films" quote. Even one of the most anti-war movie produced in the west, 'Platoon' falls short, because we never see the Vietnamese perspective. Years ago when I was in a NATO military, the majority of recruits watched 'Full Metal Jacket' at one point or another, and what is supposed to be an anti-war movie ends amping up the troops for basic training.

Lastly, you nailed it with your explanation of dialectics and materialism. I found these topics intimidating when I started reading into marxism a few years ago and a straight forward and simple explanation with diagrams like what you have is key to learning. Cheers.