A look at historically-inaccurate feudalist video games

Approaching Lords&Villeins' inaccuracies and how sim games often end up incentivizing the player to pursue the collective outcome.

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

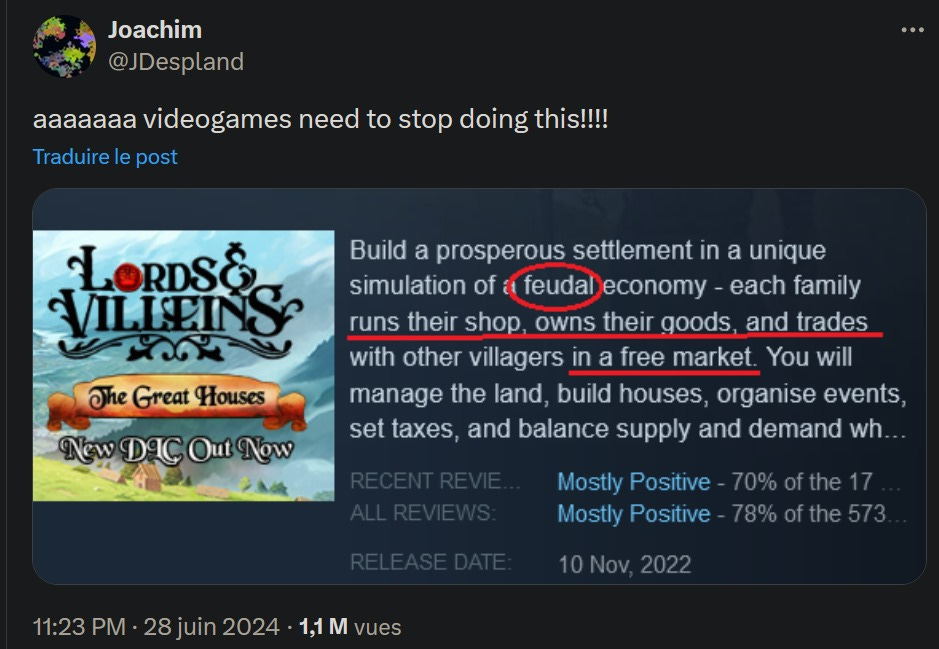

I’ve been playing a video game called Lords and Villeins recently after its first DLC came out and was announced on Twitter. I was not the only person to notice the news however, and you may have seen this viral tweet that gathered more than 1 million views:

In the picture, keywords in the description of the game — provided by the developer itself — have been highlighted. Those are the words ‘feudal economy’ contrasted to the ‘free market’.

It is true that Lords&Villeins is not a very accurate feudal simulation, but the capitalist characteristics outlined above — of serfs running their own shops and trading goods in a “free market” — are actually not even in the game! Rather, the game’s inaccuracies stem deeper from two fundamental problems: 1- it is possible to make the player roleplay as a lord, but it is impossible to actually make them a lord. Thus, 2- the mechanics of the game will inevitably end up incentivizing the player to work towards the collective welfare of his villagers, and not just on the welfare of one character.

I have to admit this is a different topic to write about for me but, keeping with the tradition of the Critical Stack, there is a usual lengthy history lesson about the feudal mode of production coming up right below.

Understanding feudalism

We have to first understand that the feudal mode of production is not characterized by a rigid set of conditions that are checked off a list. To properly assess a mode of production (the system of relations guiding material production and the continuation of society), we need to look at who produces and who owns the result of that production.

All analyses of feudalism must begin at the very simple fact that in Europe at least, 90% of the population worked in the fields — and this remained true for the entirety of the medieval period. Crop yields were low, and the produce of harvests first went to feed the family that grew the crops, and then to feed the lord’s family who appropriated what little remained. Everything else serfs did, they did on top of working the fields — the clothes they sewed, the iron they mined, the animals they hunted, the bread they baked, the wood they cut.

It was only in cities that we saw a clear separation between farming and craft work, but we’ll get back to that soon.

The lord owned land, and by extension he owned the people living on that land, the serfs. This system was directly inherited from the slave-owning mode of production that preceded it, and some parallels can be made. Serfs for example were not allowed to leave their land without the lord’s permission. According to the Political Economy Textbook of the Soviet Union, they were also in the earliest stages of feudalism submitted to the corvée system — for three or four days a week, they would work on their lord’s property directly, for free, as a tax for being allowed to use and exploit the lord’s land to grow food. This was the only tax owed to their lord in the earliest stages of feudalism, a tax being an obligatory payment owed regardless of usage. If they used property belonging to the lord, they would have to pay for it of course; but I don’t consider that a tax by itself, but rather a payment or a bill to settle.

This early system meant that serfs had to work on their own property with their own tools, and then do the same work for the lord afterwards, still using their own tools and of course labor for it. It also meant that the lord owned his own fields and workshops on top of the ones owned and exploited by his serfs. The lord would then feed himself and his family (generally known as the demesne, which refers to the land used by the lord directly but also the people in his care) with the work performed by his serfs during those days. At no point did the lord have to till the fields and harvest the wheat himself.

This arrangement was not very interesting to the serf, who was more concerned with working on his own field than the lord’s field, especially if he was going to use his own tools and farm animals for it. Thus the lord usually employed overseers to make sure his serfs performed the work he put them up to. This could range from tilling the fields to milling the grain, chopping wood, doing carpentry work, etc.

Later, as food yields improved and the system evolved, this system was partly replaced by the tax in kind.

This is what most people think of when they think feudal times. When harvest time came around, serfs set aside a portion of their yield that went to the lord as payment for being allowed to use the land. In Lords and Villeins, this system is represented through a fixed percentage taxation of the seasonal production — if the farmers harvest 100 bushels of wheat in the season for example, the lord can take 10, 20, or even 50 percent of those bushels for himself and his family; you are the lord after all and can tax your serfs however you like. In historical times, the taxation would be set early on in the year and it was the serf’s job to meet the quota. Medieval Europeans did not even have a symbol for percentage points! Thus the quota was given to the serfs in terms of total production: X bushels of wheat would be required after harvest time. If you couldn’t meet that volume, you would owe backpay to your lord, i.e. debt, which you could be forced to work off in the corvée or pay the next year.

This system could not work any other way simply because of the forces of nature. There was no telling in advance how many grains of wheat a plot of land would render when it came time to harvest. As harvests happen seasonally, with work being required on the field all year long, the tax could only be paid once a year and in a lump sum. Finally, this system forced serfs to fully utilize the land they had been granted — which, because it belonged to the lord, meant that he wanted to see it being used.

In most cases, tax in kind was used alongside the corvée, as it only concerned the agricultural yield — food is the basis of society, after all. Serfs still had to perform other tasks for the lord, but were called on less often when the tax in kind system came around. After all, the work they previously performed on the lord’s field was now performed on their own field, but with the same end result: the lord taking the proceeds of that work.

Finally, as the exchange of goods became more widespread as villages and cities grew, tax in kind was replaced by a more modern form of taxation, paid purely in money — but this took centuries to happen. This also coincided with the apparition of capitalistic relations in the cities, which I bring up for the second time and I promise we’ll talk about them soon.

In Lords&Villeins, feudalism is represented much more differently and in some ways looks closer to the managing of a modern business at the scale of a whole village.

A game starts with three families (of between 3 to 9 members each) under your control on an undeveloped plot of land, each with their specific set of skills: fishermen, foragers (who cut down wood and craft planks), and farmers. We are already departing from the historical necessity of most of the population having to grow their own food. In Lords&Villeins, only the farming families are able to make use of fields.

Each family and has their finances and needs simulated, and they trade with each other in the village economy. The farming family will sell some of their harvest at the market, and will then use the money to buy planks from the foragers, with which they can build their house.

The first issue is that you, the player, is responsible for ordering the family’s house to be built and furnished. This makes sense in the game as Lords&Villeins is a colony sim and not a city sim — the difference between the two is that the scale of the game in colony sims is much more up close and personal. You have to designate a plot of land to become a household, and then decide which material the walls will be made of, place the beds manually inside the house, etc.

Historically, this was of course not decided by the lord but by the family themselves. The lord granted land, and the serfs used that land however they liked (yes, even under feudalism they had some independence). In practice, this land often ended up being mostly fields as they had to pay a tax in kind in the Fall. A peasant’s house was usually just one big room that served as everything. In the game, once you set down the blueprint for the construction, the family members will then start purchasing the required materials and build their house themselves.

As we outlined above, historically serfs also dabbled in more than one trade. Historically speaking, all those starting families in Lords&Villeins would each have their own field, likely portioned off a bigger collective field, and be responsible for tending their portion: they would feed themselves with this work, pay their tax in kind, and then might keep what little was left afterwards for next year, or sell it if possible. They would all know how to cut wood and build a house with it, forage for food in the forest, hunt and fish outside of harvest season, mend and sew their own clothes, repair their own thatch roofs, etc. They would do this in the common lands, lands designated by the lord to belong to the whole village.

Serfs were the ones who built castles and erected bridges. Not the lords. While the more capable and educated among them could become quartermasters in these tasks — I remember a demonstration of how trigonometry was used historically to make spiral staircases in castles, for example — this was not their primary job. Their primary job was tending to a field so as to feed themselves and their feudal lord. When a castle needed to be built, which took several years, the peasants were relocated to the construction grounds and put to work there. If you’re interested in how these were built, I recommend watching this documentary that follows the (modern) construction of a medieval castle using only historical techniques.

The specialization of labor is at the core of Lords&Villeins: if you want to start building higher quality houses or craft stations, you need to invite a carpenter family to your village. If you want to hunt meat, you need to invite hunters. But you will then also need a butcher family to prepare the meat: they will buy the animal carcasses from the hunters, butcher them for meat, and then sell that meat on the village market.

This is a highly advanced system of logistics that makes little sense for the feudal needs. Imagine trying to explain to a hunter in the year 1254 that you will buy their animal carcass, butcher it yourself, and sell the meat back to them — and that this actually makes total sense to develop both their hunting business and your butchery business. This is a very anachronistic abd capitalist understanding of older relations of production.

Where the game has to lose accuracy is that due to this system of “specialized families”, things that the lord would normally charge for effectively becomes the private property of serf families. In feudal times, mills would belong to the lord — they were huge projects to build, and only the lord would have enough money to make one, using the corvée workers to actually erect the stones and wheels. The mill would then be exploited by the lord’s demesne, who charged for each use of it. Meanwhile the lord enjoyed the use of his mill for free, and used the tax in kind obtained at harvest (the grain the serfs surrendered to him) as well as the corvée to grind it for him and bake it into bread. In that way, the lord did not lift a finger himself and instead exploited his serfs’ labor twice: once when producing grain that they had to surrender to him, and a second time by having to grind it for the lord.

In Lords&Villeins, the system is entirely different. A milling family has to be invited to the village, and then given a mill. In that way it works more like private property, though you are free to take away their mill at any time (so not actually private property!) At the end of the season, the miller family gives you some of what it produced, i.e. flour. In the meantime, the farming family produces grain that they then sell to the miller. The miller then turns that to flour and sells the flour on the village market. The baker then buys that flour and makes bread, which he sells.

In the actual feudal system on the other hand, each family would go to the miller — or use a hand grinder if they couldn’t afford the mill — and grind their own grain, leaving with their own flour. By the time they had grain to grind, they had also surrendered the part they owed to the lord under the tax in kind.

This is why I said that in some ways, the game plays more like a business simulation: if we abstract the mechanics, what you are actually doing is hiring workers for a specific job (hunting, farming, cutting wood, etc), and providing them with the tools to get started. You then tax them some of what they produce, which can be seen as making a profit after they have produced what they need for themselves — much like you make more money for your employer than he gives you as your salary.

In fact, you even employ serfs not through the corvée system but by forcibly hiring them into your estate — though this was not unheard of and is historically attested to. In this arrangement, the serf becomes a full-time worker to your family; building things on your properties, cooking meals for your family and other servants, etc. They are paid a wage at the beginning of each season, making them officially employees (though they are not allowed to leave your employ without your approval).

But what is a business, even in capitalism, if not the collectivization of production?

The game loop is therefore mostly based around balancing your economy and welcoming new families to your village to increase production and make your family richer so they can afford nicer things (such as brick walls over wattle walls for their home). To help give some objectives to follow, once a year your own lord will request your family send him products worth X amount of gold. Failing to follow these increasing demands will hurt your relation with your lord and I assume make you lose the game — I have yet to fail a delivery in my games so I couldn’t say.

Hierarchy in feudal times was very rigid and very neatly defined. Lords&Villeins brought some of that hierarchy with their latest DLC, but loosely defines it as a series of equal “Great Houses”. Following historical feudalism, the family you play as would most likely be barons, one of the lowest ranks and essentially similar to a mayor, who may not even have been a noble himself. The baron had to report to a count who owned an entire county. The count was usually (but not always) under the rule of a duke, who ruled over several counties. At each step, all of them had to surrender taxes in kind to the higher power — a system inherited directly from the tributes of ancient times, when it was too difficult to coordinate tax payments as they had to be transported over great distances with no communication, and as such conquered territories were simply held to paying tribute in resources once a year. Feudal lords also had to, in exchange for the land, swear fealty to their own lord and promise to assist in times of war with their own troops.

This stratified hierarchy was at times and in some places more detailed, but always pyramidal with everyone having someone above them, except for the king. The clergy followed the same structure, but was wholly separate from the feudal rights: they owned their own land, with their own serfs, and did not pay taxes to the lords but to the Clergy, i.e. in Europe and in this time period the Catholic Church.

Trade — at least trade for money, and outside the village — was not as widespread as the game makes it seem. By and large, serfs produced their own tools and food. In Lords&Villeins however, it pays to set up a marketplace with stalls as well as a caravan trading space as soon as possible. The marketplace is used by your serfs to sell off their own items inside the village: they will need one if you want them to trade with each other, solely through the cash system (and since a farming family will never go cut the wood it needs to build its house, you need the marketplace to progress). Caravans work in the same way, but as wandering traders: they visit your village every so often, and might bring in items you don’t or can’t produce yet that your villagers may want to purchase.

Historically though, trade was more developed in the towns and cities — Paris, London, Samarkand and Rome to name a few notable medieval cities. These towns were first developed as centers of crafts in the slave-owning system which preceded feudalism, but while the system fell down and the old owners of the workshops disappeared, the crafts remained. In the early feudal system, craftsmen could not depend entirely on their craft to survive, and had to tend to their own garden as well. Women engaged in the spinning of flax to make clothes — this shows the limited scope of trade in early towns. There were no stores with shelves full of clothes back then, everything was made to order.

Over the centuries, the craftsmen were able to focus more on their craft and settled in newly growing towns and near monasteries to offer their services. They were wholly different from the serfs as they were not bound to the land and thus didn’t belong to the lord. Over time, as the craftsmen perfected their work, lords would prefer to purchase their quibbles from them rather than their own serfs, as the quality was better.

Conversely, this also meant that serfs found themselves returning back to a primarily agricultural economy in the countryside, as they found no more buyers for their crafts.

Towns which arose on the land of lords eventually found themselves booming, and with that came the struggle for more independence. While craftsmen (in the later medieval period) did not belong to the land of the lord, they still had to obey his laws, use his courts, pay his taxes — either in kind or money — and could be exiled at any time if they ran afoul of the lord. Booming towns, which sometimes found themselves to be much stronger than the local lord in terms of wealth, productivity or simply sheer numbers of inhabitants, thus fought with weapons or made land purchases for their independence, becoming their own authority. In their struggle for emancipation, cities organized in guilds. Guilds were organized around one trade, and laid down rules for this trade (such as the length of the working day, the number of apprentices each master craftsman was allowed to have, etc).

Guilds started as a progressive force in that they fought for emancipation from feudal ties, as well as in the increase of commodity production that they were able to achieve (by focusing solely on production and training new craftsmen instead of complementing their main agriculture work with some odd jobs here and there), and represented an early form of labour organization. However, with time and as their strength grew, they ended up becoming monopolies strictly regulating the flow of new craftsmen into the cities, fixing prices and wages, eliminating competition, etc.

Further struggles erupted inside the cities: journeymen (workers who were employed day by day by the owner of a workshop) organized in secret brotherhoods to defend their interests, which were mainly higher pay and shorter workdays that could be as long as 16 hours a day for insignificant pay. Journeymen could also rarely become masters of their own, which would have allowed them full membership in the guild and the right to own their own workshop. Indeed, the guilds did not want newcomers in their rank as their interest was to run a monopoly inside their city. When these brotherhoods organized, guilds started persecuting them, showing that the struggle was internal to the city and external between the city and the local lord.

As commodity production evolved, merchants started to appear as there came to be things to trade in quantity. They later made their own guilds to defend their interests as well; hose are attested to existing as far back as the ninth and tenth century in Europe, but remember that the medieval period in Europe started after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD. This means that merchant guilds appeared at around the halfway mark of the medieval period, and some 300 to 400 years after it was established! For comparison, this is about how old capitalism is today.

This is also when the transition to tax in money started to happen. In order to trade with travelling merchants, lords had to have their own treasury, as merchants only accepted coins. It was thus convenient for the lords to transfer the tax in kind (surrendering a portion of the serf’s agricultural production) to tax in money (surrendering a portion of money). This is not represented in Lords&Villeins, and instead both taxation systems exist side-by-side: when granting a zoned land to one of your serf family in the game, you can decide whether to tax them in kind or in money, but not both. Both forms of taxes are required however, as you need the actual grain and bread to feed your lord’s family (which exists in the game just like the other villagers), but also need cash to trade inside the village and with caravans. With that said however, the game makes it seem like it’s entirely possible to successfully set up a village relying on only one type of tax.

Before tax in money was levied, it is entirely possible that feudal lords did not own a single coin to their name. However, they still owned wealth of different kinds: they owned resources, and they owned the surplus product of their serfs’ labor. They owned debt as well, a form of money (though less formal).

Remember that in feudal times, travelling merchants would have no interest in buying things such as grain or vegetables beyond what they needed for themselves, as food was grown by literally 90% of the world. They were also not interested in trading with serfs who barely owned a field and a plow, but looked to sell valuables to lords and master craftsmen — the trip had to be worth it, after all. Most often, they would set up shops in nearby towns and the lords would make the trip there, whereas in Lords&Villeins they happily come to your backwater village to trade your worthless baubles.

This is where the game starts to get the second half of its name. Villeins were serfs who were allowed to leave their lord’s land and travel, and in the stratified hierarchy of feudalism was a slight step above being a serf. They were still bound to a lord however, and were not exactly freemen like they might be in independent cities. Most villeins were not travelling craftsmen, but worked as laborers or farmers here and there.

I find that all colony sims end up falling in a trap: in the end, what’s good for your village as a whole is good for you the player. And because you play as a lord in L&V but are not actually one, and because you are so involved in the life and well-being of your village (down to placing buildings yourself), you have no reason not to improve the lives of your villagers. There is no reason your lord’s family needs to be the richest: you cannot actually spend that money or show it off as wealth status, it only exists in the confines of a single-player 2D game. You don’t need the biggest manor: there is no gameplay advantage to having a bigger house than your family size requires.

What you actually need to do, conversely, is making sure your villagers don’t feel compelled to commit crimes or die of starvation, because every villager that is unable to work for even a day means lower productive output, which means a bigger chance of messing up your supply chains and fewer taxes.

Conversely, this is the complete opposite of how a feudal lord would act. He had a direct, material interest in exploiting his serfs as much as possible to garner more privileges and wealth for himself. He had an interest not in solving crime for the sake of justice but to remind people of his power. Mind you, imprisoning or executing a serf still meant losing a capable worker back then; jailed criminals had to pay for their own food and would owe payment to the lord for the use of the jail cell for the duration of their sentence. However, lords could trade serfs between themselves and actually often did that, selling or buying serfs from other nobles. It’s entirely likely that a criminal serf would be sold off to another lord as a means of exile, which completely bypasses the need to house and feed them for the duration of their sentence.

Ultimately, all colony sims trend towards rewarding cooperation and the collective well-being. In those games — Rimworld, Dwarf Fortress, Oxygen not Included or Alien Dawn to name just the famous ones — you don’t control just one character, and you don’t even control several. Most of the time, you can’t control your population directly but have to issue orders (more accurately called suggestions) that a villager will take up when they are able to.

You are incentivized to identify not with just one character, but with the entire community that forms your ‘colony’. That’s why I don’t think Lords & Villeins could even accurately represent feudalism; this is the trap all colony sims end up falling into, no matter how hard they try to avoid it — by simulating a cash economy in this case.

Most of these games, in fact, completely forego any attempt at simulating an accurate economy as it might exist in a community of humans, and money is often only used to trade with outside merchants who might bring items you need but can’t produce yourself yet. Inside the ‘colony’, we see a collective, communistic relation of production prevail: in most of those games, your NPCs [non-player characters] will perform tasks as they are needed, and store the surplus resources from these tasks in a common stockpile which everyone is free to pick from.

There is no concept of private property in these types of games: there is most often a common stockpile of goods and everyone is free to take what they need from it. Some items such as weapons or armor might be assigned to a character to use in combat, but can easily be re-assigned. It is not equipment that belongs to you the player: it belongs to the community, and is only lended temporarily, until someone else needs the item.

Some colony sims have tried to introduce private property, but often to the dismay of players who feel bottlenecked when an NPC manages to appropriate most resources for themselves and, because of the lack of direct control, can’t be made to give them back. This is also likely why Lords&Villeins has a mechanic for seizing goods from a family, with the only penalty being a slight loss in your relationship with that family. In real feudal times serfs owned their property and could not have it seized without good reason, but had such meager possessions (by design!) that there was nothing much to seize either way.

Even in Ratopia, a game that revolves around collecting taxes from your rat population and putting them to work on your orders for payment (thus entering a cycle of collecting tax and spending it), players quickly find themselves working for the common outcome of the colony over the privileges and luxurious life of the queen character which you are meant to embody. If one rat falls, the whole colony falls.

What makes these games fun is not trying to get one character to rise up above all the others (although it is certainly possible in some of them if the player so chooses), but growing the settlement as a whole: you are invested in all characters at once, and not just one. The mechanics of the game inevitably result from this premise, and incentivize you to care about all your citizens — present and future — instead of just the one you might control in other games.

You are not quite a god or even a guiding hand in colony sims; they are different from strategy games such as Age of Empires, in which you control individual units directly. Because your ‘colony’ also simulates so many characters at once (between 9 and 40 depending on the game), we can’t say that you play as your village’s population all at once either. They are also different from god-games such as Black and White or Spore: you don’t have divine powers in colony sims, or mechanics relating to a god. You can’t effect change in the material world of the game beyond giving orders that, most often, your citizens will get to when they get to it.

Rather, the player becomes sort of a personification of production. Not quite the invisible hand of the market, but simply the authority of collective production. If not enough planks are being produced, then it is your job to make more saws so more wood can be processed. If food is becoming scarce, then you have to increase the size of the fields and get more people to work on them.

This is something that people in real life are very good at noticing: they don’t need someone to tell them there is a lack of food around. But to make a game, one needs mechanics and challenges to give the player. Hence the role of the player in such sims is to make sure everything works smoothly. You become the economy itself, and find that for things to work efficiently, you have to forego private property entirely so that all can work for the collective: if one thing breaks down, then everything is at risk of collapsing in a chain reaction and it’s game over.

I find that these games actually speak to our cooperative nature as humans living together in society. No matter how hard they may try to simulate private property and encourage selfish self-interest, colony sims ultimately end up badly replicating these systems because they become very limiting when trying to make an engaging game.

This doesn’t apply solely to colony sims either. I’m reminded of how players self-report that they almost always choose the good options in dialogue over the evil ones in RPGs. I’m reminded about how in city sims (a much larger scale colony sim), players strive to eliminate homelessness and work to create a city where all social issues are tackled. This is very different from what we see every day in our own lives, where homelessness is rampant and unaddressed, and everyone is out for themselves; we are led to believe that this is the natural state of the world, that this is how it is and always has been, but then — as soon as we’re given the chance — we do things very differently from how we are told we naturally act.

Have you noticed this in any of the games you’ve played? Feel free to comment below.

All of my writing is freely accessible and made possible by the generosity of readers like you. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting me. I’m on Ko-fi, Patreon, Liberapay.

Bitcoin (BTC SegWit network) - bc1qcdla40c3ptyrejvx0lvrenszy3kqsvq9e2yryh

Ethereum (Ethereum network) - 0xd982B96B4Ff31917d72E399460904e6F8a42f812

Litecoin (Litecoin network) - LPvx9z9JEcDvu5XLHnWreYp1En6ueuWxca

Upgrade your Substack subscription for $5/month or $50/year:

Share this essay: