Outlast 2 and the politics of non-violence

A horror video game teaches us that the true horror is inaction.

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

This essay contains no media that may scare or shock readers.

This essay contains spoilers for Outlast 2 and Resident Evil 7.

This essay contains topics some readers might find difficult, including talking about cults, miscarriage, child abuse, sexual abuse and suicide.

Outlast 2 is quite an old game by now, and I couldn’t fault you for not knowing about it. Released in 2017 (7 years ago already), Outlast 2 is a horror video game that even today remains both a terrifying experience and a very edgy one even in this post-COVID world. While this sequel to Outlast decidedly had some similarities with the perhaps bigger name of Resident Evil 7 (though the two games came out within three months of each other), Outlast is very different from the Resident Evil series in that the player is mechanically unable to fight at any point.

To quickly recap the plot of Outlast 2, it goes like this:

Journalists Blake and Lynn Langermann decide to travel to the fictional town of Supai, Arizona to investigate the murder of a pregnant woman.

While en route, their helicopter crashes and Lynn is kidnapped by a Christian cult.

Playing as Blake, the player then embarks on a mission to save his wife and leave this place they found themselves in. Horror and gore ensues.

This plot is surprisingly close to the plot of Resident Evil 7 — there, husband Ethan Winters receive a last message from his wife Mia, who disappeared in Louisiana, and goes to rescue her.

The reason I’m bringing up Resident Evil 7 however is not to bash one or the other for plagiarism; I don’t believe this could have been the case as both games came out in the first quarter of 2017. Rather, I want to draw attention to the fact that a major point of the Resident Evil series is that the player gets access to an increasingly deadly arsenal of weapons to defend themselves with, while in Outlast weapons themselves do not seem to exist.

Certainly, the reason weapons are not available in Outlast 2 is to reinforce the psychologically anxiety-inducing aspect of the game. You play a defenseless reporter whose only means of survival is to run away or hide while (human) enemies run after him. This creates tension, as the player often has to sneak or sprint around several enemies that will not stop pursuit until the player finds the exit spot on the map.

Contrast with Resident Evil. In this game, the psychological horror aspect comes from the fact that weapons require ammo. Ammo however is scarce to come by, and each enemy requires plenty of bullets to kill. On top of that, inventory space is very limited, forcing players to make tough choices on the fly, often as a zombie is rapidly approaching them. Do you try and take it down, or do you think you can run around it without getting bitten?

But I’m not particularly here to argue about mechanics. Both games have been out for 7 years now, and I don’t intend to write a review for either. Rather, I want to focus on the politics of non-violence that Outlast 2 displays — whether consciously or not — through its choice of mechanics, and the implications this has in the real world.

We all know of Gandhi or Martin Luther King, two champions of non-violence who, it is said to us as children, appealed to the conscience of oppressors and showed them our shared humanity, so much so that oppressors realized the error of their ways and stopped oppressing Indians and Black Americans.

Never mind the fact that these stories are embellished; Gandhi slept naked in the same bed as young girls and MLK did use violence (albeit violence inflicted upon him) as a tool of protest.

Rather, we know very much less about Baghat Singh and Malcolm X, who were contemporaries of both figures and who organized movements and fought in parallel to Gandhi and MLK — but they didn’t champion a message of non-violence, quite the opposite in fact, and so they don’t appear in school textbooks.

From this observation, we can safely say that there is a reason non-violence is instilled upon us from our youngest age. We grow up preaching peacefulness, which we are led to believe is what consists of non-violence (because violence disturbs the peace), which in turn becomes passivity — the idea that any form of violence is bad and never justified. And certainly we have all heard the idiom “we don’t solve our problems with violence” or “violence solves nothing,” as if violence is a tool of a bygone era, something for uncivilized people who have not yet discovered better means to solve their problems such as courts of law, the police force, or perhaps even the marketplace of ideas.

Blake Langermann shows us that these politics are a dead-end that will only lead to defeat. Outlast 2 — and I thank its developers for it — makes a great case that violence is political, and as such can be enacted for both progressive and regressive aims.

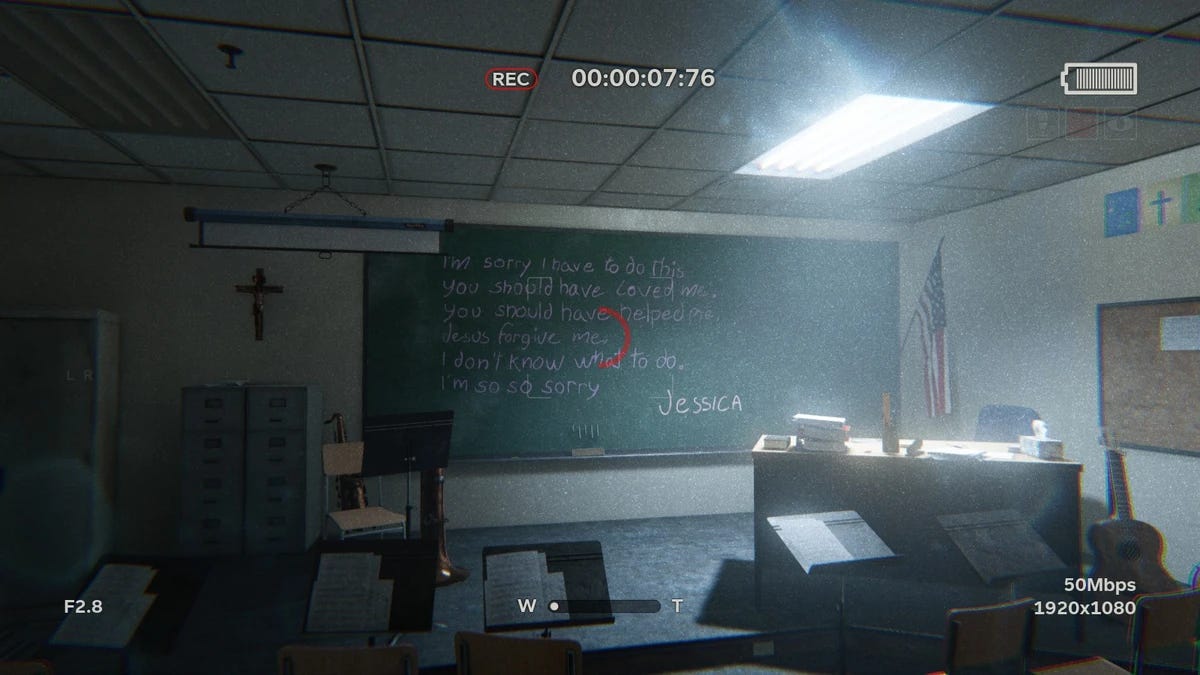

One major plot point in Outlast 2 are flashbacks that Blake Langermann, and thus the player, go through at several points during the game. These take him back to his childhood as an elementary student in a Catholic school, and his relation with his childhood friend Jessica. They are mandatory sequences full of scares and backstory, and form an integral part of the game on top of his predicament with Lynn and the cult.

As the game progresses and we play through more flashbacks, we understand that the character of Jessica was sexually abused as a child by one of the priests at school. Finally, near the end of the game, we play through a scene in which the priest tries to drag Jessica away from Blake, and Blake — or rather, the player — lets it happen through inaction.

This is the first catalyst that I think really breaks players away from the immersion. In that instant, all players that I’ve seen play the game wanted to reach through the screen and punch the priest — thus using violence, despite the game preventing them from doing so for its entire story. But the game would not let them act; inaction is built into the player character: Blake (but only Blake) embodies peacefulness throughout the entire game and refuses to do anything that might upset that state. But peace is not the absence of injustice, it’s only the absence of doing anything about that injustice. In other words: it’s inaction, preferring to be passive in the face of challenges, choosing to sit down and accept your fate instead of doing anything about it.

There is certainly a difference between acting and using violence. But the game doesn’t make that difference throughout its entire 8-hour storyline, nor does it want to. In Outlast 2, refusing to be violent is the same as refusing to act. And I think that’s a very powerful message because it’s so contradictory: the game has spent the better of 8 hours reinforcing passivity in the player, only for all of that to come crashing down the instant it puts us in a believable, sadly very real scenario.

In that moment where Blake could have chosen to save his friend, he chose instead to be polite, to not upset the balance of things, to remain passive and abandon her. And he was punished for it.

In that same flashback, Jessica takes the reins as Blake leaves her behind, and she attempts to run away from the priest. Unfortunately this was the wrong choice, the game tells us. The priest catches up to her and it’s implied he throws her down the stairs, breaking her neck. Blake witnesses the scene and, to save himself, the priest instead makes it look like Jessica hanged herself, which creates lingering trauma in Blake who later grew up thinking himself responsible for her suicide.

Outside of these flashbacks, which happened in Blake’s childhood, it seems that everything that happens in the game to progress the storyline happens in spite of Blake and not because of him. A recurring sequence in the game is to let the player loose in a somewhat large, open area (such as a farm or a town square) where they have to find the exit located somewhere on the map. To create some tension, various enemies are then deployed on the map and hunt down the main character.

Keep in mind that in Outlast, all enemies are humans like you and I; there are no supernatural monsters in this game like there are in other horror games. Would Blake be wrong for killing or at least incapacitating those that are trying to kill him?

Violence certainly seems to be working for the cult. They are entirely misguided in their aims (trying to birth the antichrist and kill him to save the world), but they are in a position of power to enact violence to serve their goals, and they do. They are violent towards Blake, trying to kill him, and they are violent towards women and babies as well (which is why I said the game was edgy in the introduction).

Would you be wrong for proverbially killing (dismantling) the system that every day is trying to enact its violence upon you? Outside of outlandish video game plots, we receive every day the violence of poverty, unemployment, police brutality, poor healthcare and inflation. Or should you be more like Gandhi’s Blake, running around aimlessly until you stumble upon the lucky exit, only to be thrown back into the same ordeal again and again?

There is no reasoning with these enemies. Blake actually tries to talk to them at several points, without success. He fails to appeal to their humanity not because they have none, but because they have goals grander than Blake and he’s not a part of them. His approach is misguided throughout the entire game, and he never changes it, and — as we’ll see — he gets punished for it.

The cult would very much prefer that you be like Blake, passively accepting your fate instead of trying to fight back against their plans. And so would the State while it continues to enact its violence against you.

The game certainly contains weapons, though not ones that Blake can use: only enemies carry a machete, an scythe or an axe, or lay bear traps for him to walk on. His only “weapon” as such is to run away and keep running until he stumbles upon the right solution that was, thankfully, placed there by the developers. But at no point does he make his own solution; everything happens around Blake and propels him further along the plot by pure luck.

For example, early in the game, Blake comes across a friendly villager who hides him in his basement so he can take a rest. When Blake wakes up, the cult leader’s right-hand woman and officer is interrogating the villager for Blake’s location. All the player can do (and thus what Blake does, by extension), is to watch this scene unfold from beneath the floorboards. He does not attempt to save the man who helped him. The man refuses to give out Blake’s hiding spot, and the officer kills him for it before leaving.

Although it’s never stated, taking the high road of refusing violence because violence is the tool of the enemy (the cult in this case) leads Blake nowhere: his savior died for nothing and Blake selfishly survived.

These events and levels form the basis of progressing in the game. As we move along and start to understand the subplot (explored via notes and other environmental finds), we can piece together the following scenario:

Sullivan Knoth once heard the voice of god through a radio and started a cult. He and his followers fled to Arizona to start a commune.

A corporation used this isolated community to test their invention (called the morphogenic field) through radio waves, which creates hallucinations and trauma-based flashbacks in people that the radio waves reach. These hallucinations take on the form of the individual’s past trauma (hence why Blake has flashbacks of Jessica). For the cult members, this took the form of visions from god about the antichrist.

The cult started trying to hunt down the antichrist. The way they did this was by impregnating women (including kidnapped women) and then killing the child after birth. They figured that eventually, through sheer numbers, one of them would be the antichrist and they would save the world.

Throughout the game, Lynn is alluded to being pregnant with the antichrist despite Blake being infertile. At the end of the game, she gives birth to a baby and dies during childbirth. Before dying, she says “there’s nothing there…” in reference to the baby. The morphogenic field gives men flashbacks of their trauma and causes phantom pregnancies in women.

The field also causes hallucinations, which in Blake take the form of the end times due to his Christian upbringing. At one point a rain of blood pours down, and the game ends with the Sun exploding in a flash of light (Armageddon).

Blake can see Lynn’s phantom baby, meaning that he succumbed to the morphogenic field entirely and is as lost as the cultists are. After one last flashback to his childhood, where the entirety of Jessica’s story is revealed, he is plunged back into reality with Knoth sitting next to him in the cathedral.

During this last confrontation, Blake sits alone in a dilapidated church as Sullivan Knoth, the cult leader sits down next to him and monologues. At the end of his monologue, the instigator of all this violence — against both Blake, Lynn and the entire commune — kills himself because he failed to prevent the birth of the antichrist (Lynn’s phantom baby). This essentially puts an end to all this misery, as he was holding the cult together, but what’s very upsetting is that Blake and the player played no role in his outcome.

Ultimately, you could take Blake entirely out of the picture and tell the exact same story. He serves only the purpose of being an outside observer to the story, a witness, with the game even reinforcing this role by making the camcorder, a tool for cataloguing and recording, a primary mechanic.

The game, despite its politics, convey a very good lesson: that refusing to act when given the chance will only end in failure. In the end, everyone around Blake dies: Jessica, Lynn, Knoth and his entire cult are all dead. Two people gave their lives to help him, and it was all for nothing too, all because Blake refused to take some responsibility and do anything.

Resident Evil’s much stronger narrative

In the writing of this piece I found Ethan Winters, Resident Evil’s 7 and 8 player-character, to be a very strong character narratively speaking.

Ethan Winters is a systems engineer, which is not too dissimilar from Blake being a camera operator. At the beginning of RE7, the first game in which Ethan appears, he doesn’t know how to use a weapon. This is notably reflected through his character animations: his reloading animation are sloppy, using a lot of unnecessary movement or taking longer than necessary to switch out a magazine. This shows that he doesn’t feel entirely comfortable around firearms and doesn’t know much about handling them. By the time of the events of Resident Evil 8, he has received special forces training and his animations and even overall attitude reflect that: he remembers to chamber the round after reloading, and is even able to switch magazines on the fly by holding two in one hand.

Ethan only comes across his first weapon in Resident Evil 7 in the introduction chapter after reuniting with Mia, when she suddenly ‘turns’ (she is under the influence of a biochemical mold that turns people into supersoldiers but Ethan doesn’t know that at this time) and tries to kill him; his first weapon is not even a firearm but a hatchet, more of a tool for chopping wood than a weapon.

While this sequence serves as a tutorial to the new mechanics the game introduced, there are certainly thematical implications to turning a weapon on your wife who is clearly not being herself (and the game even giving you a pistol to shoot her with afterwards), but it’s telling also that Ethan only receives a weapon to defend himself — he didn’t bring one with him and didn’t have access to one until Mia started attacking him — and that this weapon is first and foremost a tool.

Contrast this to Blake who simply refuses, for no stated reasons, to even carry a weapon with him despite coming across many implements that could be used as one and fighting against very real bleeding humans, not bioweapons that can regenerate their wounds at will.

Even the initiating factor for both storylines are completely different: Blake got into a helicopter crash (something that happened to him), whereas Ethan chose to drive out to Louisiana to find his wife.

Once the Baker family, who will be the main antagonists, is introduced, Ethan receives a clear goal: he correctly reasons that if he wants to save Mia, he will have to confront those who kidnapped her, and that he will be unable to leave until they are taken out. Moreover, he receives help through the phone from Zoe Baker, the daughter of the family, who escaped the mold infection, and Ethan strives to save her too once she expresses that she wants to leave but has been unable to.

Although there is something to be said about the trope that a man is saving women as if they couldn’t save themselves before he came along, Ethan shows agency and purpose throughout the entire game, even taking out the source of the mold that turned this secluded family into bioweapons at the end of the game — another bioweapon called Eveline (a staple of the Resident Evil series, which all happen in the same universe, is that zombies are a result of the military-industrial complex research on turning people into manufactured supersoldiers). Ethan’s use of violence is shown positively and productively, always used to achieve goals that are not self-serving or the product of gratuitous violence, but rather to make things better even if a few eggs have to be broken.

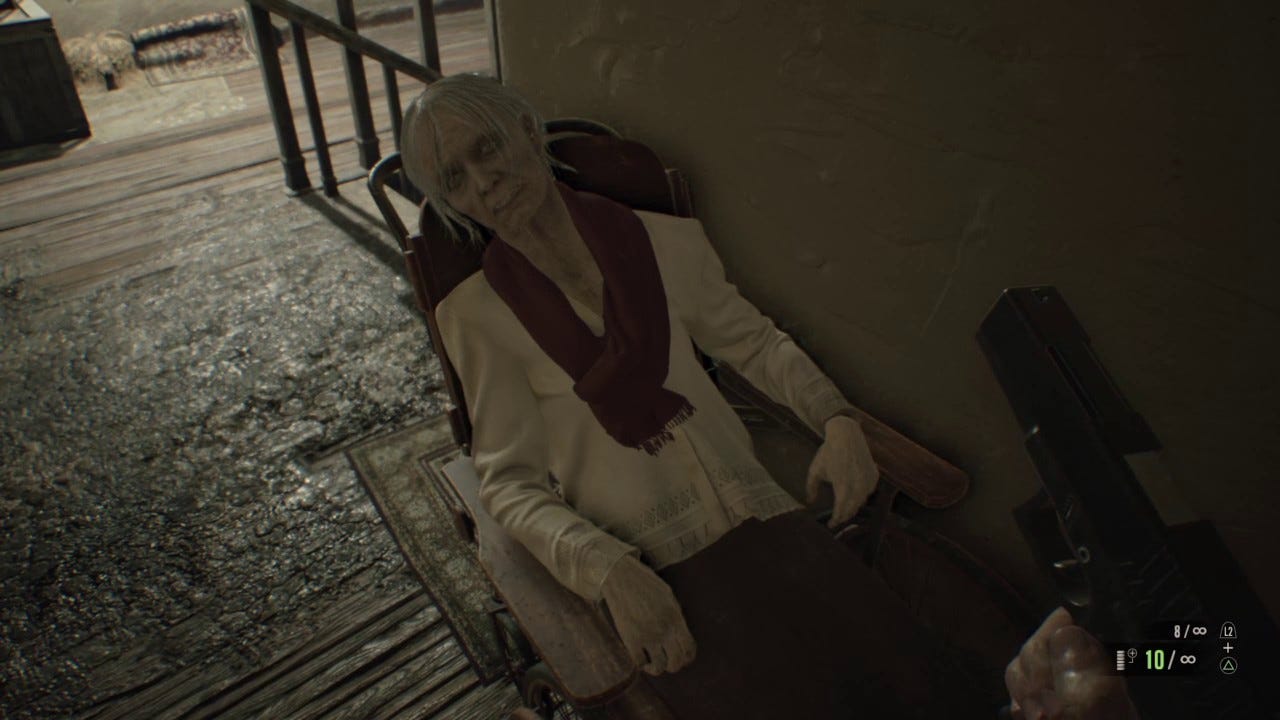

Ethan didn’t resort to violence as the first solution either, but always as self-defense. For example the player will come across a catatonic, wheelchair-bound grandmother at several moments in the Baker mansion — and Ethan never harms her because she is visibly harmless. In fact, the game itself prevents the player from attacking her. The grandmother is actually the source of the mold infection but, at the times Ethan comes across her in the mansion, he doesn’t know this yet.

The game also takes some lengths to show that weapons are a double-edged sword and not an innocuous tool. In the early game, after the introduction and once Ethan is free to roam through the Baker house, the player inevitably comes across the shotgun prominently displayed in a well-lit area, held by a statue that looks like it’s holding it out to you. Upon picking up the shotgun however, the room locks down and it becomes impossible to leave with the shotgun (which only has one round in it when you pick it up). To get out of the room, the player must put the shotgun back on the statue, which will lift the lockdown. The player will be able to pick up the shotgun later after acquiring a decoy somewhere else in the house to replace it with.

This mechanic teaches the player that weapons are not a given even in this life-threatening situation: they must be earned, and ammo is scarce — every shot must be carefully considered before pulling the trigger. This is certainly another tutorial for the player, but it also conveys thematical choices and an even stronger message than Outlast 2’s extreme nonviolence: In Resident Evil, you are allowed to use violence and even make mistakes, but you are encouraged to minimize and learn from them.

Blake’s only motivation in Outlast is to reunite with his wife and escape, and who knows what will happen after that. At no point do either Blake or Lynn address the question of what they are going to do after leaving: if they’re going to alert the authorities or even to take down the cult themselves. Blake and Lynn are only here to document the world: interpret it, as Karl Marx said, when the point is to change it.

Ethan changes the world: through his agency, which includes the application of violence (because he reasons correctly that violence shouldn’t belong solely to his oppressors), he removes the source of the biochemical mold that transforms people into violent monsters and even cures one of them from the infection, in a difficult choice that leads to one of two endings.

Of course, very few of us will (I hope!) ever have to face a murderous cult or biochemical mold. But we live around violence every day: we’re just not the recipient of it most of the time. Protestors, the homeless, the poor and the marginalized are some of those who receive state violence on the daily. Something as innocuous as an eviction notice is a form of violence: if you refuse to leave your home, then the police will forcibly drag you out of it. The threat of violence is always implied.

To swear off violence entirely because the “bad guys” use it, when we could instead use it to make the world a better place (i.e. to improve things) is effectively to give in to them and let them use a very effective tool for progress simply because we think we are too “good” for it. The state doesn’t think it’s too good for violence when it bombs children abroad, or when it arrests anti-genocide protestors with its police force.

And certainly, it’s no secret that the military-industrial complex and its actors use the same justifications for their use of violence. But a tool is a tool; it has no agency of its own until it is wielded. Much like the hatchet can be used to chop wood or to defend against an attacker, violence can be used to kill innocents or it can be used to stop more violence and improve people’s material conditions.

Revolutions brought about capitalism. In Britain, in the United States, in France and in many other countries, the violent overthrow of one class by another was required to change the system from feudalism to capitalism. Were these revolutionaries too good for violence, we might still be living as serfs under a local lord.

We see then that violence has a political character and is not inherently good or bad. The violence of the Christian cult in Outlast 2 is regressive; it’s used to realize a prophecy brought about by hallucinations. But the violence in Resident Evil 7 is progressive: it’s used to prevent more destruction and tragedy. Zoe’s family was taken away from her by the mold, which was purposely leaked by Eveline, the original bioweapon, into the Baker household. Mia was taken away from Ethan by the Bakers. Ethan was himself killed and infected with the mold. All of the above are a form of violence that was inflicted on people against their will. To then turn around and say “okay, they did this to you, but you’re not allowed to hit back as that would make you just the same as them” gets us nowhere. If Ethan had done that, he would have been no closer to his goals than Blake was by the end of Outlast 2.

One might say Ethan’s actions even show a liberatory character, as he takes on a product of the military-industrial complex (Eveline) that will keep infecting people if left alone — similar to the depleted uranium ammunition that litters Iraq after the US invasion and still causes cancers and birth defects to this day.

Violence can be used for political aims, and these aims can be progressive or regressive. Using violence as “Israel” does against Palestinians is regressive, because it is used as a means to exterminate the indigenous population of Palestine so that “Israelis” may settle it unchallenged. The mere act of settling occupied land is already a violent act in itself, involving forced displacement and genocide to expedite the process and make room for settlers. Palestinian violence to resist this settlement is thus progressive because their violence is the only means to prevent their extermination. It is a violence of resistance that came about after diplomatic means (the Madrid Conference, the Oslo Accords, the Camp David Summit…) failed to produce any solution that would have made violence inappropriate. As Clausewitz said, war is the continuation of politics by other means — and thus has itself a political character.

All of my writing is freely accessible and made possible by the generosity of readers like you. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting me. I’m on Ko-fi, Patreon, Liberapay.

Bitcoin (BTC SegWit network) - bc1qcdla40c3ptyrejvx0lvrenszy3kqsvq9e2yryh

Ethereum (Ethereum network) - 0xd982B96B4Ff31917d72E399460904e6F8a42f812

Litecoin (Litecoin network) - LPvx9z9JEcDvu5XLHnWreYp1En6ueuWxca

Upgrade your Substack subscription for $5/month or $50/year:

Share this article:

Insignificant goals, such as : "the struggle for rights ; for higher wages ; all sorts of solidarity with someone and somewhere ..." - cannot justify violence .This is too little to make sense in destroying the "enemies", no matter how bloodthirsty sadists they are. Such a "solution to the problem" will be similar to "banal" terror - targeted, local, ... useless, scaring potential supporters away from you and attracting various nihilistic sociopaths. A change in the social order in the state (in its own!) , according to a pronounced and understandable program, brings violence into a legitimate field , as a result of inevitability , gives it meaningfulness . The ghostly "rights" (handouts) negotiated from the state by the first generation will be emasculated and then taken away from the next generation. There must be a Goal , with a capital letter !