Copaganda: The purpose of a system is what it does

Recently, I was searching up a video game called Ready or Not, and was not surprised to see there was some amount of controversy surrounding it.

Part of this controversy revolved around what the developers of the game decided to put into their game, and subsequently remove… quite a few different times. For example, they used to have a level that involved responding to an active shooter incident at a middle school. Later, after controversy, the level was changed to a high school, and then to a college setting after further controversy.

But for our purposes, I am more interested in the comparatively minor controversy surrounding the theme of the game, which some have dubbed to be copaganda.

In Ready or Not, the player takes the role of a SWAT team leader, and has to progress in various locales in increasingly difficult missions. The player will have to direct his team on the ground, facing tense and urgent situations. The game prides itself on not holding anything back, as seen by the school shooting mission. Other missions involve crimes upon children, a family selling weapons illegally to help pay for their mother’s surgery, a mass shooting situation in a night club, arresting and more often killing ne’er-do-wells and other violent criminals, and in general bringing order to the chaos — a theme the game repeats often, with slogans such as “Stop the killing, stop the dying” adorning the police station.

I call the copaganda debate a “minor” controversy because there is actually very little debate around it. All I could find mentioning it were two relatively short reviews on the Internet. Yet, this hasn’t stopped fans of the game from continuously complaining about ‘the people who call this game copaganda’, which form the vast majority of the results if one searches for this topic.

It’s come to the point where even cops are weighing in with videos, comments and essays on it — against a controversy that never existed, but which they think threatens “their” game. Nobody is trying to cancel Ready or Not from sale. In a Youtube video titled, appropriately, Ready Or Not is not Copaganda | An Officer's Perspective, a cop happily defends what he calls his ‘choice of career’, and immediately reminds us that he puts his life on the line, that he has saved people with narcan while responding to calls — his video opens with him praising himself (even if unwillingly) for his own job.

Cops believe fully in their own propaganda because they are trained this way. They are trained to see themselves as the last line of defense against a society that wants nothing more than to kill each other at the smallest opportunity. They are trained to see everyone as a potential criminal, or at least someone who is hiding something. Beat cops, when they still exist, are actually drafted from areas they don’t live in. It’s a very misanthropic view of society, but this is what the police is.

Many people defend the game’s themes by saying that it paints a bleak picture of police work, one that is not attractive. Nobody wants to become a cop after playing Ready or Not exactly because of how dark, dangerous and sickening the situations they respond to are.

And in my opinion, this is exactly what makes it copaganda. Unfortunately, I have yet to see anyone else point this out.

What Ready or Not does is not make police work look beautiful so that people will rush to submit their application — which some of its defenders claim is the only way copaganda works. Propaganda is not so single-minded, and has no reason to be.

The point Ready or Not makes is that police work is messy and difficult, and is best left to trained professionals who know better. They’re the ones that respond to these horrific situations, and so we owe them some respect. The protagonists of the game are ultimately painted as special people, because they do it, and they can take it.

This is perhaps not even intended by the developers, who are based in New Zealand and paint a hyper picture of what they understand police work in the US to be. But again, it doesn’t have to be intentional; it’s even possible that the developers intended for the opposite themes to come out. But, between intent and reality, there is a concept we will shortly come back to: the purpose of a system is what it does, and nothing else.

As an example, there is a mission early on where your team responds to a weapons smuggling operation in a suburban neighborhood. Through contextual clues and the mission briefing (if they remember to read it), the player finds out an immigrant family turned to this business when the mom was diagnosed with late-stage cancer as a way to pay the medical fees that insurance won’t cover. They knew it was dangerous, and the mother was even the one who called the police because she disapproves of this business.

And yet, everyone in the house dies in the end because the game’s AI makes them only able to shoot at your team like trained operatives instead of surrendering, inviting rightful retribution upon them. While many people resonated with the plight of this family because it hits close to home for many US nationals (that is, the high cost of healthcare), they also went through with the mission, carrying it out to the end so they could unlock the rest of the game in a sort of ‘hardships are only a temporary setback on the road to success’. It’s the same reason we kept playing Spec Ops: The Line, a game that has the player commit war crimes in Dubai so he can see the end of the game. Except Spec Ops made a point with it: at the end, a character point blank tells you you could have closed the game at any time (gone home from the mission, in context), but you didn’t. You wanted to keep going.

With that said, the morale of the story falls a little bit flat when you bought the game for $50 on release with no way of refunding it.

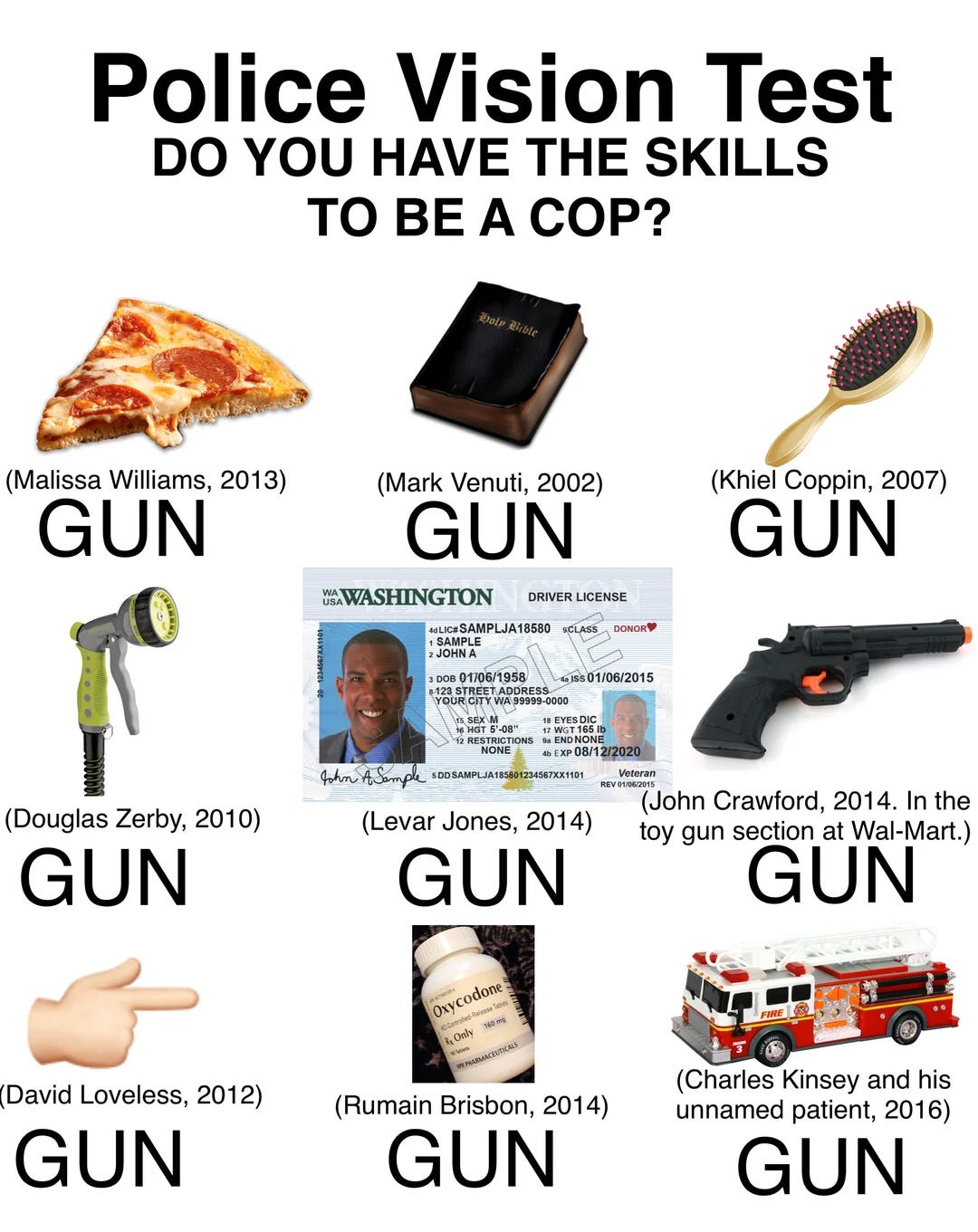

Ready or Not paints a picture of everyone being a hardened criminal, driven by need, yes, but also by a criminal personality, because how else are we supposed to interpret their refusal to surrender? “Some people are just like that”, we have to assume. If the player doesn’t respect the rules of engagement, their teammates will turn on them and kill them. This, some people say, is also an example of how the game can’t be copaganda. But once again, the opposite is true: in real life, incidents of brutality, wrongful deaths, police assault, police failure to respond, etc. are swept under the rug. Time and time again police lie to cover their own, with their own ‘unions’ providing legal counsel in their defense. Taxpayer money is then spent to marginally compensate the victim (if they are still alive) and, at best, the officer is moved to another department. None of this reality seeps through to Ready or Not. Rather, the game is premised through a highly fantastical portrayal of the police: a police that responds to highly sickening situations, that answers the call of the badge each and every time, and that always gets the bad guy… after the crime has already been committed.

It is also very interesting that at the time of writing this essay, Ready or Not is receiving console port which saw the developers tone down some aspects of the game (as per their words: VOID said it had to adjust levels of gore, nudity, violence, and the "mistreatment of children" ahead of the July 15 console release). On Steam, where the game originally launched in 2023, the player base is now review-bombing the game with Negative ratings, calling the developer out for this ‘censorship’.

One recent review reads: “They made their money from you—the PC players on Steam—and now, out of sheer greed, they’re appeasing console market regulators by censoring the game to meet their demands”

The topic of ‘censorship’ is a big one in this slew of new reviews. Of course, the fanbase is not necessarily a monolith. But it’s interesting, looking at the Steam reviews, to see that this topic of ‘censorship’ comes back often. According to its community, this is a game that does not glamorize police work, one that leaves them feeling sick after each mission, while at the same they want more of this. Other reviews state it more plainly: “I love when non-compliant civilians reach for their phone as fast as they can in order not to waste the officer's time. May or may not result in a mag dump <3” (281 people found this review helpful, 137 people found this review funny)

This might be funny if it wasn’t true.

One of the top-rated reviews for the game echoes the same sentiment: “what do you mean unauthorised use of deadly force?? she was taking photos to cancel me!” (681 people found this review helpful, 389 people found this review funny).

At a time where police in the west has a problem with white supremacists in their ranks, this starts to explain what kind of person takes enjoyment in playing this game and ‘punishing’ civilians with state-sanctioned retribution.

Most top-rated reviews revolve around the potential for violence one is able to inflict in this game. The choice of playing as police is not so innocent; it’s a trope, and all tropes exist for a reason, but this one is very simple: the police have a state mandate that provides their power. Their violence is lawful, and thus correct and without repercussions, but I’ve talked about some of the politics of violence before. If the game wanted you to come out of it thinking “gosh, police work is messy and maybe we need to do something to prevent crime instead of just responding to calls that never end” then it objectively failed at that. Judging from the reviews, that is clearly not what players took away from their time played.

Ready or Not is propaganda in the same way that mafia movies are propaganda for organized crime, anti-war movies are propaganda for war, and so on: to portray something is to inherently make it relatable and endearing. “I don’t think I’ve really seen an anti-war movie”, said Truffaut in 1962. “Every film about war ends up being pro-war”.

When Tony Montana dies at the end of Scarface, the intended point is that crime doesn’t pay. Yet, the opposite was conveyed: Montana (played by Al Pacino) has become an icon for the ‘live-fast-die-young’ crowd, and those that would wish themselves to be part of this crowd. Yes, he died at the end. But he had a hell of a good time doing it.

The reason Ready or Not exists is not necessarily to make a grand point about money; this is the major takeaway. The developers may not have intended for any of these themes to seep through, but they do, because an art creation quickly escapes its author when being unveiled to public opinion.

Ready or Not exists to make money. In this quest for profit, it will depict a story, it will explore mechanics and ultimately, it will ship a finished product that can be purchased. Some people point out, “Nobody would play a game where you sit at a desk for ten hours until you get a call to the same house for the third time this week for a domestic dispute”. In saying this, they think they are making a point against copaganda, but the opposite is true. Fiction shows us the high-octane, high-stakes sequences and normalizes them, as if the day-to-day of policing was like this or ought to be like this. When one is trying to sell a product, to portray something is to glamorize it, there simply aren’t many other ways to sell fiction. Of course, this isn’t even going into a related point, about how much the US army is embedded in the production of war movies for its own propaganda purposes.

The power of capitalism is that it subsumes all criticism of it into itself. Ultimately, anything that tries to criticize capitalism ends up reinforcing it in some way. It can be packaged and sold as ‘counter-culture’, but it still makes money to a capitalist.

Capitalism’s underlying mechanism is that it turns everything into a commodity, that is, a product to be bought and sold. This is how we find ourselves with t-shirts of revolutionary figure Che Guevara for example, a man who made it his life mission — and died from it — to fight for liberation movements across the world.

Che was killed by the CIA after several years of failed attempts and has now become a commodity in the belly of the beast that killed him: his face adorns t-shirts that one can purchase, and thus his face has been completely severed from his life. He has been canonized, so to speak, by those he fought, robbing his revolutionary life of substance.

In the same way, Ready or Not subsumes criticism of the police. Nobody wants to be in a club shooting situation, and nobody wants to respond to it. “But, aren’t you glad someone is responding to it?” is essentially what the game is saying. It portrays an idea of sacrifice from the police — a possession one gives up willingly for the benefit of others, in this case potentially giving up their life. Sacrifice, in historically Christian societies [i.e. most of Europe and North America] is seen as one of the most virtuous act one can do. It intrinsically creates sympathy for someone.

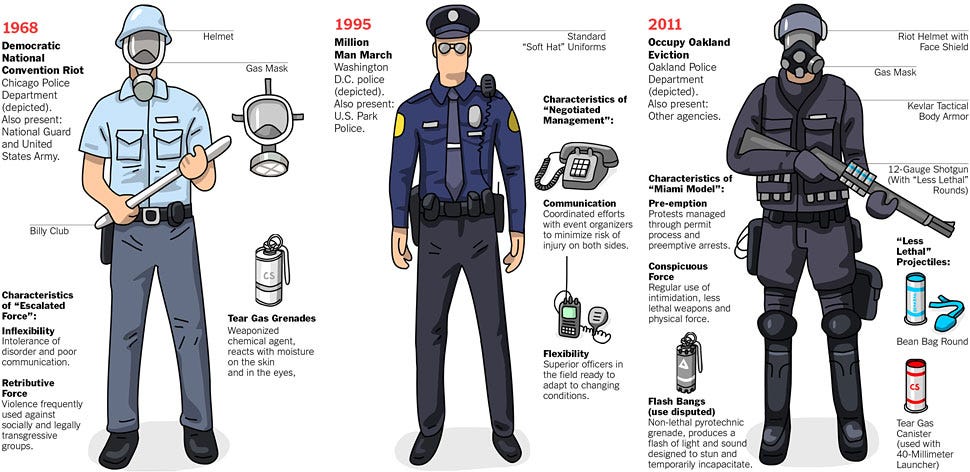

Yet in the U.S. alone, being a retail worker is about as dangerous to one’s life than being police (the reference hides it but 37 police amounts to 3.35 homicides per 100,000, far from the 7.7 cited, which amounts to a 1.75 difference). Yet we never hear about how retail workers ‘put their lives on the line every day’ or aren’t ‘sure if they’ll go home this evening’ or how they need a bigger gun and riot gear to do their job. And maybe retail workers reading this would love to have all of this! But, only the police is given this kind of equipment (especially in countries where firearms are not as readily drawn out by suspects; the US is kinda special in that way). They are the only ones asking for more equipment of violence to do their job with, whereas anyone reasonable in society asks for less violence in general.

It doesn’t matter if the developers intended this or not: what matters is what it portrays, i.e. what it reinforces in society. The next time one sees the SWAT raiding the wrong house, they might think “but they do so much for us, cut them some slack!” Incidentally, this is a widespread trope in the internal affairs subgenre of police fiction too: “don’t investigate this cop, he does good work aside from the brutality.”

Let’s not forget that police rarely, rarely respond to the types of incidents Ready or Not portrays in its missions. I will be focusing on the U.S. here, but the same is true almost everywhere that has an equivalent to SWAT. In the United States, SWAT teams often enforce warrants on drug charges — as part of the famous War on drugs that puts predominantly Black men and women in private prison for non-violent incidents, destroying families and, more importantly, community organizing against state repression (the same state repression that puts them in prison, for one). There is a dog shooting epidemic in the US, with police (including SWAT) shooting between 10,000 and 25,000 beloved family pets every year as a way to remind people of their absolute authority: if you challenge the police, we will come after you.

Often, they serve warrants at the wrong address, terrorizing innocent families and children in the middle of the night. They also shoot the dogs while they’re at the wrong house, if you were wondering.

But Ready or Not does not portray this actual side of the police. The game presents them as heroes on the one hand, allowing the player to live a mass shooting taboo on the other — a topic for another essay but to start with, just look at the Steam reviews delighting in their ability to shoot unarmed civilians. There is a taboo being broken, which makes Ready or Not counter-culture too, like Che Guevara t-shirts, but a different type of counter-culture. And we can say this because reviews for the Grand Theft Auto series don’t mention this potential for brutality at all; in GTA, killing civilians is not taboo.

Urgent situations, that is, situations that were not engineered by the SWAT but that they respond to, ultimately make up less than 8% of all calls (depending on the place). Most of what they do is arrest small-time offenders on drug charges, sending them into the pipeline of for-profit prisons that sees them stay in the system their entire life so that the most value can be extracted out of them. In Massachusetts, 63% of SWAT warrant raids between 2012 and 2014 were for suspected drug crimes, but drugs were actually found in less than 25% of those cases. Meanwhile, the police continues to militarize itself from surplus Iraq War equipment, learn from the IOF directly, and ultimately come to fulfill a role that is very, very far from the one Ready or Not — and other countless cop fiction — portray.

And of course, we can’t forget about ‘swatting’, the practice of calling the SWAT on someone’s house “as a prank”. This practice has led to wrongful deaths, and is made possible because the police is so militarized (and this is true the world over) — leading them to respond violently to all situations.

Because of this, the police actually often escalates situations instead of solving them. This is not new, and not unique to the US. They don’t even prevent crime; rather, they show up after the fact when it has already been committed to take a statement and do nothing with it.

You’re likely familiar with Stockholm Syndrome, the term describing how hostages supposedly develop sympathy for their captors. The true story is different. In 1973, robbers took employees hostage in a Stockholm bank. The police response was so terrible — escalating tensions — that one hostage, Kristin Enmark, was actually on a call with Prime Minister Olof Palme asking him to call off the police who were endangering the hostages caught in the crossfire of their guns, retreated in the small vault with the robbers. Palme dismissed her, and told her point blank she should be prepared to die on the job; to him and his career, it was more important to make a show of taking out the robbers, even if the hostages had to die in the process.

Nils Bejerot, the psychiatrist called to the scene (who later coined the term), was also criticized by the hostages for agitating the captors instead of deescalating the situation. He invented the term afterwards to deflect blame and protect both the police and himself.

The hostages felt safer with their captors than with the authorities; one robber, Clark Olofsson, actively shielded them from crossfire — think about that. Later, the hostages pleaded for the police to let the robbers leave, which would have solved the situation: the hostages would have been free to go, and the captors could have been arrested at a later location. But Palme categorically refused, insisting police storm the cramped vault. The hostages became their own negotiators between the police and the captors.

The term ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ was then coined to absolve the psychiatrist and authorities of any wrongdoing, and we’ve been talking about this non-existent syndrome ever since.

Perhaps the most accurate part of Ready or Not is that it is highly difficult for the player to arrest suspects, leading them to shoot first and ask questions later, something the police also excels at. To create arrests, the player needs to equip ‘less-than-lethal’ weaponry; but no character will ever willingly surrender otherwise, promoting a certain picture of the nature of SWAT work: going after hardened criminals who want nothing more than to kill people with no rhyme or reason. In fact, there are two different terrorist cells operating in the fictional city the game is set in.

In this way, the game promotes a “thin blue line” view of society, something police departments love repeating, actually believing that society would break down if they stopped doing their job (arresting kids for cash and protecting private property) for a single day. Must we talk about Uvalde, where the police stayed outside for hours, even arresting parents for attempting to go into the school while a shooter was killing children? This was a real situation, and the complete opposite of what happens in a similar mission in Ready or Not.

Again, none of this has to be a conscious choice by the developers. These are simply emergent themes from creating a work of fiction; I doubt there can truly be a police game that does not eventually paint the police in a positive light somehow.

The purpose of a system is what it does. This means that no matter what one may claim their institution is supposed to be doing on paper, no matter what they want it to be doing, no matter what they founded it to do — the purpose of it is what it does right here, right now.

And we see that the police’s purpose is not to make streets safer or arrest violent criminals. Their purpose is to become militarized, to purchase military equipment so that the army can buy more from defense contractors. Driven by an endless pile of money, they can arrest innocent people to send them to for-profit prisons that make a few business investors very rich. On top of which, the militarization allows them to repress popular unrest more easily, including peaceful protests and community organizing. Several activists connected to the 2014 Ferguson protests (protesting the police shooting of Michael Brown) have been found dead in mysterious circumstances.

Yet when white-collar crimes are committed, such as a health insurance CEO being investigated for excessive denials, which directly kill people, it is not the armed SWAT or police being sent, but lawyers. They get treated with care and respect (presumed innocent, a principle not afforded to minorities), because they are property owners.

In that regard, police act like a gang. Thus the purpose of the police is to be a terror gang: that is what it does, and so that is its purpose. If its purpose is to change, then it must be doing something else.

When you fail to pay rent and your landlord asks for your eviction, who gets called? Social workers? Mediators? Lawyers? No; it’s the police, to drag you out of your home. When you march in the streets, who gets called to look over the march? Journalists? Local government employees? No, it’s the riot police, ready to charge into the mass of children, women and disabled people if they feel like putting a stop to your expression of free speech.

Again, this isn't unique to US police forces. Nearly all police worldwide now train with the IOF and own decommissioned military equipment. They universally deploy 'less-than-lethal' weapons, a misnomer marginally better than its predecessor, 'non-lethal weapons'. For one thing, rubber bullets are not actually rubber; they are metal projectiles coated with a thin layer of rubber. These have caused fatalities but keep being purchased, all to fuel a billion-dollar industry and put you in your place when you start making too much noise. Similarly, tasers are frequently deployed against suspects who reflexively resist restraint and continue to cause deaths due to the intense electrical current delivered through the prongs.

But Ready or Not is not like that. Ready or Not wants you to do everything by the book, and will contort its scenarios for you to be able to do everything by this very, very lenient book.

We see copaganda elsewhere too, of course. The Wire is often praised for its characters. Early on in the series, an overeager recruit brutalizes a Black youth while serving a warrant, rendering him blind in one eye. The matter is swept under the rug by the intervention of the chief of police, also a Black man, who ultimately sides with his fellow police rather than a teenager of his community. But the matter is never brought up again, it goes away as quickly as it happened, and the show goes on: the chief of police continues to climb the ranks, and over the time we get to spend with the character in the course of the series, we start to naturally identify with him, his good qualities and his mission. It’s like the police brutality never happened, and we, the viewer, end up putting it out of our minds too.

Police officers in The Wire are neglectful, corrupt, downright terrible at their jobs, and violent — but nothing is done about it. At times, it felt like the show was taunting me. It’s saying “yes, this is what the police is really like, whatcha gonna do about it?” Police kill innocent people in the streets and then we go home, put on a series, and the same thing happens. It seems inescapable.

For more fulfilling portrayal of authorities, I would actually recommend Chinese dramas. One in particular, In the name of the people (available with subtitles on YouTube), presents an entirely different point of view. In this series, Hou Liangping is an investigator for an anti-corruption department in the Chinese government. His job is to investigate government officials on corruption charges. The series also has strongly-written, relatable characters. But more than that, Hou doesn’t have a weapon (like most police in China, even if he is not technically police) and doesn’t get in dangerous situations every other episode, or even at all. Episodes don’t deal with outlandish “this bomb will explode and the hostages will die in 2 hours if you don’t solve this riddle” plots that are commonplace in western fiction. His opponents are government officials, i.e. people in places of authority and power, not marginalized communities that are being stereotyped and on whom it is socially acceptable to beat. Care is taken by the investigators not to harass people if they don’t have a case against them. Culprits try to save themselves with their power and authority, and sometimes they win, and sometimes they fail — but ultimately, they get their comeuppance (something that I find lacking in today’s ‘gritty’ trend, where everyone is a self-serving asshole and has no redeeming qualities).

Early on, a target of investigation manages to escape to the United States before the police can prevent his flight from leaving — they were trying to ground the plane at the airport, but needed to know which one he was on. No guns, no chase, just an order to the airport to delay a flight so they can come pick him up. In the United States, he finds that life is not like it was in China; he is penniless, nameless and powerless, unable to even access his ill-gotten funds. Unlike Tony Montana who died, he has to live with the consequence of his actions: never being able to go back to China, never being able to see his family again, left all alone in a country that cares nothing for him.

The parable is clear: by flying too close to the sun, you will achieve nothing but burn your wings. The parable in The Wire was different: if you fly too close to the sun, the sun will look away and pretend nothing happened.

What happened to Che Guevara happened to countless other people and their ideas. It happens in both manners: at times “defanging” revolutionary figures that threaten the present state of things, and at other times reinforcing the present state of things. Fiction, or at least mainstream fiction, is thus perhaps only a mirror of the present state of things and one of its defenders. But in other places, the mirror will reflect something different. Because the purpose of police is different in China, Chinese fiction will present their police differently: they go after corrupt officials, they uphold the law, they work for the collective good, etc. In Chinese cop shows, problems are solvable — they are not the result of random or unfixable social ills (like we often hear that poverty cannot be eradicated, that it will “always exist”; China disagrees). These are themes of growth and hope made reality, rather than the usual “the world is terrible and everyone is a psychopath” themes we tend to see in western fiction, and is perhaps explained by the Chinese’ own optimism about their future, when compared to the West.

As always, please feel free to post Palestinian fundraisers in the comment section.