If we want to effect real change in the real world, we must accordingly use real tools: applying creativity as a tool

What creativity actually is and how you can harness it.

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

Creativity is generally understood as a sort of beast that walks in the same direction as us, travelling alongside us but not with us on the many journeys we embark on. You can’t tame it, you can’t willingly make it do something it won’t do — but sometimes, just sometimes, your paths align and it helps you cross a hurdle you were stuck on.

Rejoice, because all of the above is incorrect, and there is a way for us humans to reach our full potential!

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Look, we’ve all seen the terrible memes. We’ve all seen the “creativity is when you are this” and “creativity is when you do this”.

It’s become a polarizing word. As the (terribly funny) meme above suggests, there’s supposedly two types of people: those that are creative, and those that aren’t. They’re the boring ones.

But creativity is not solely within reach of a select few who are able to imagine dragons cooking up their chicken roast — which is more an indication of imagination than it is creativity. It doesn’t have anything inherently to do with art, despite the namesake of ‘creative arts’ — which would imply the existence of the uncreative arts, somehow.

No, the answer is even better: if we want to effect real change in the real world, we must accordingly use real tools. Thus we have to reframe creativity in a way that allows us to use it as a real tool. Anything short makes it meaningless and better suited to drive a wedge between people, like the meme above ended up doing when it was published on the internet (though things always move in contradictions, and the meme eventually reached cult status and ended up making people bond over it).

We all use our creativity; it is one of the gifts we are imbued with on virtue of being human. Creativity is a capacity we own, like the power of reason or inference.

I would give this definition of creativity:

Creativity is the ability to deconstruct systems and interactions into their most fundamental components, so as to rebuild them in a different manner than they were before.

There are two components to this definition: the first is the deconstruction, and the second is the reconstruction.

We all use creativity every day because we all solve problems every day. A problem doesn’t need to be anything big; a problem, by definition, is anything that has a solution to solve it. If there is no solution, then there is no problem per se — but even when the solution is not readily apparent, it doesn’t mean there is absolutely 0 solution. It often just means that we haven’t found it yet, and this is where design tools like creativity help us.

If I had to give a visual example:

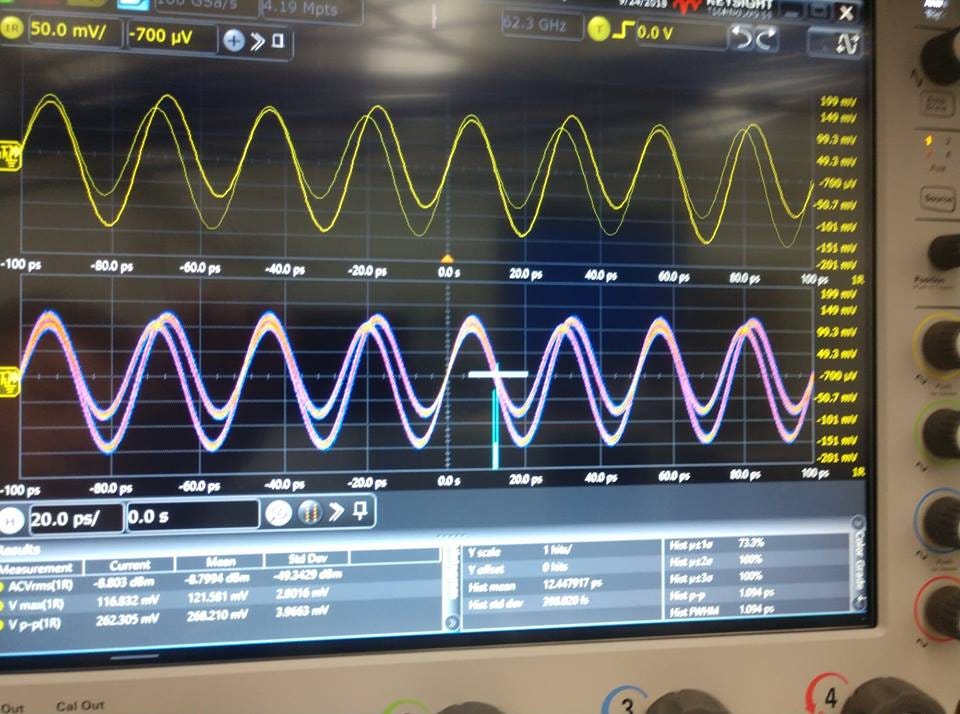

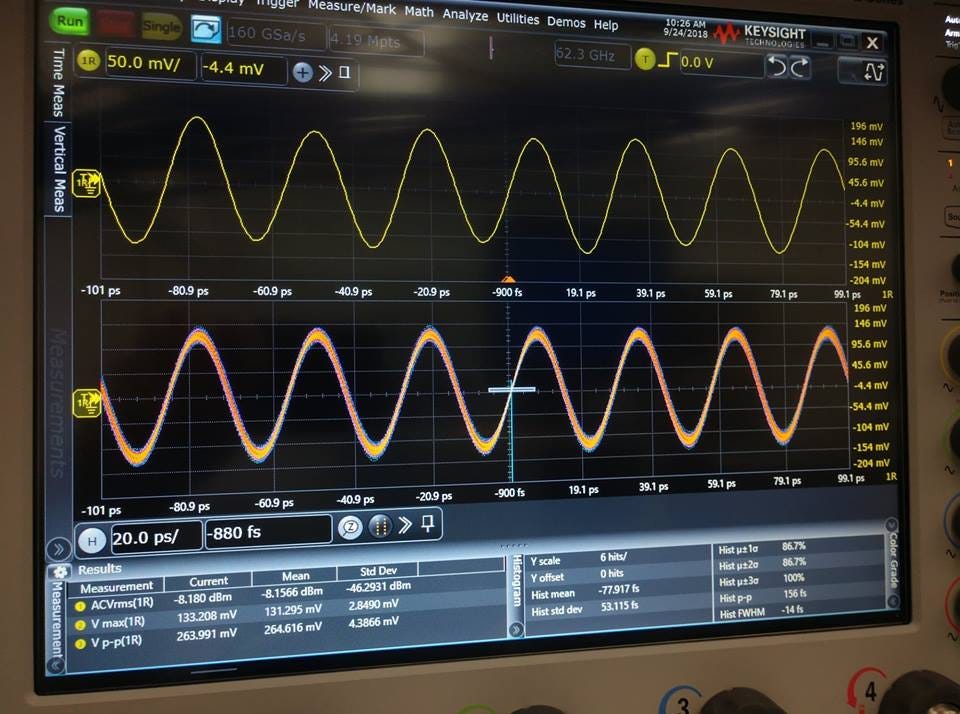

Think of two overlapping waveforms; one of them is your solution, the other is where you are at currently. They are not quite aligned, and may never be (sometimes it just turns out like that, and that’s okay). But our goal is to get them to be as aligned as possible so that they look like they form only one wave. To do this on an oscilloscope, you have to twist the knobs and push the buttons, until you get this:

Let me break it down a little more. The laws of the universe exist around us. Gravity, thermodynamics, physics, etc: they’ve existed for as long as the universe has been what it is now. They are real, and we exist under their weight, whether we are aware of it or not. Indeed, the force of gravity on Earth has been 9.81m/s for as long as the Earth has existed as it does today, which far precedes humanity. We’ve lived blissfully unaware of this numerical value for millennia until it was finally calculated and recorded down, while still living under its objective existence. In other words, the acceleration value is real whether we can calculate it or not, whether we do calculate it or not, and whether we are even aware it exists — or not. Gravity will continue to exist on Earth even when there are no more humans. This is what I mean by objective existence.

It falls upon us as humans to apply our agency, i.e. our capacity to effect change in the real world, and uncover the objective nature of the world. Rarely do things fall into place without wilful involvement.

Once we take realization of the problem and its corresponding solution (for which there can be many), we can then effect change.

There is a huge gap between an idea and its application. We all come up with new ideas on the daily, but implementing them is a very different thing. Implementation can take on hundreds of different characters. For example, if I asked for a piece of furniture to sit down on, I could end up with either a chair, a stool, or a commode (at convenient waist height). All of these will allow me to sit down, but all of them look and work differently in how they are meant to be used. And of course, I can’t sit down until I actually have the piece of furniture in front of me. The idea of wanting to sit down does not replace actually sitting down.

The point of design — and indeed, the point of making change — is not solely to have the right idea. Everyone has ideas, and everyone likes their idea. But to actually make something happen beyond the confines of one’s imagination, one must also be able to bring this idea into the world, and this is where creativity can help us as a tool, if we are able to harness it. Once we clarify the purpose of a tool and how it works, then it becomes much easier to figure out ways to reinforce it.

We can train creativity by doing deconstruction drills. Take things you have around you, and break them down to their fundamental components. I have a metal water bottle on my desk — so, what is a water bottle? Breaking it down, we could say that (among other things) a bottle is a sealed container that can be carried and opened at will. From there, we can ask (and of course, answer): does it really have to be a tube? When does it stop being a container? Does it really have to be opened at will? And perhaps many others questions that you can think of by taking note of these fundamental interactions. From there, upon answering these questions, we can design a new type of water bottle. Here’s a question: does the container absolutely have to be rigid, or can it be malleable to fit into the hand, like a balloon?

And it only took me a minute to type up this paragraph above from start to finish by applying this principle of creativity. Is it a good idea to make a malleable water bottle? Maybe! We’ll only know through experimentation — experimentation being how we make experience of the world and assert our place within it as agents of change; experimentation is how we come to correct ideas and solutions. Through experimentation, I can carry my idea to its implementation (making an actual tangible bottle) and test it out.

When studying things in a design methodology, there is no judgment. We look at things as they are, and take note of their characteristics. A mistake I commonly see is wanting to skip steps, thinking we either have all the information we need, or that we can do both at the same time (gathering information and solving the problem). When I study users, I gather as much information as possible and don’t even think of the problem they’re facing until I’m sure I’m done with that part. It ought to be the same when deconstructing something: breaking down something to its fundamental components implies that we must be able to look at them without judgment to be effective. In the case of a water bottle, saying it is a cylindrical sealed container would already pigeonhole us into thinking about cylinders. And to be honest, the same could be said of calling a bottle a sealed container specifically (again we experiment to find out just how far we can push the concept, if there is an actual reason to push it).

The skill of design is not in remembering the methodology and applying the rules as prescribed. A designer’s skill is in being able to ask the right questions, consider the right solutions, and notice the right things.

Ultimately, we train a skill. And the more you train something, the better you will be at it. Doing exercises using real, actual problems trains you to, well, become better at solving real problems. When I was in design school, we did a lot of fake exercises. I always left dissatisfied with the fake exercises because you can’t focus on the crux of the matter: actually solving a problem. You get a short one-paragraph brief talking about the fake company, and you have to make them a fake logo without being able to get any feedback from the client or any additional information you may want as a designer. You can’t steer the fake company towards the correct framing of their problem because the company doesn’t exist, the company is your teacher and your teacher wants you to follow the instructions. We’d often end up making pretty logos, but never really understanding how we got there or why our logos mattered. This is how you get designers that will make cool-looking logos but when asked to explain them will start to talk about how the subtle curve on the lowercase i is calculated to curve like a human smile and the logo is built on the golden number and they will draw all sorts of circles and lines to show just how mathematically correct their logo is. It can have no substance, because the fake exercise did not allow for it to have substance.

And sure, a pretty logo fulfills a purpose (i.e. at least one of them). It makes people want to look it, and it might help make it memorable. But is that the only purpose of a logo? I am leaving the question open for you to answer.

Like all skills, one must walk it before they can run it. Design thinking — including the application of creativity — helps us solve complex problems, and there’s a reason millions of people around the world use the methodology and swear by it. The examples I gave above may seem very basic and obvious to you, but that would only be because you’ve already passed this 101 stage. In real world situations, we often start from the very abstract and almost hopeless.

First ideas often are. A real situation I’ve been in is this: “we want to do a course on AI for job-seekers.” This is often all you’ll get to start with, and you have to render a finished product in one week. But we did it. Using a design sprint, which is doing the 5 steps of the design method over 5 days (one step per day and sticking to it), and being teamed up with over 8 people who were not designers (showing that anyone can learn this skill when it’s taught properly!), we submitted a prototype on the fourth day and had it tested by real people on the fifth day: in our case, it was a web page that explained what the course would teach (that’s about all we could do in just one day!) It doesn’t have to be the actual course, because that was not the problem for the client; the problem was not “we don’t have this course”, the problem was “is it a good idea to offer such a course?”

In the final analysis, we hold that labor is precious and should not be squandered. We do things for a reason, and not just to occupy our time or busy ourselves — a failure of capitalism is that it wastes labor on things that are useless, just to keep people busy at their jobs because their day has been paid for and so it will be disposed of by the capitalist. It is human to want to reduce effort expanded, and to apply labor (and logically, effort) productively and with the least waste. It is a capitalism-induced fallacy to claim that things must be difficult to be worth it.