If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

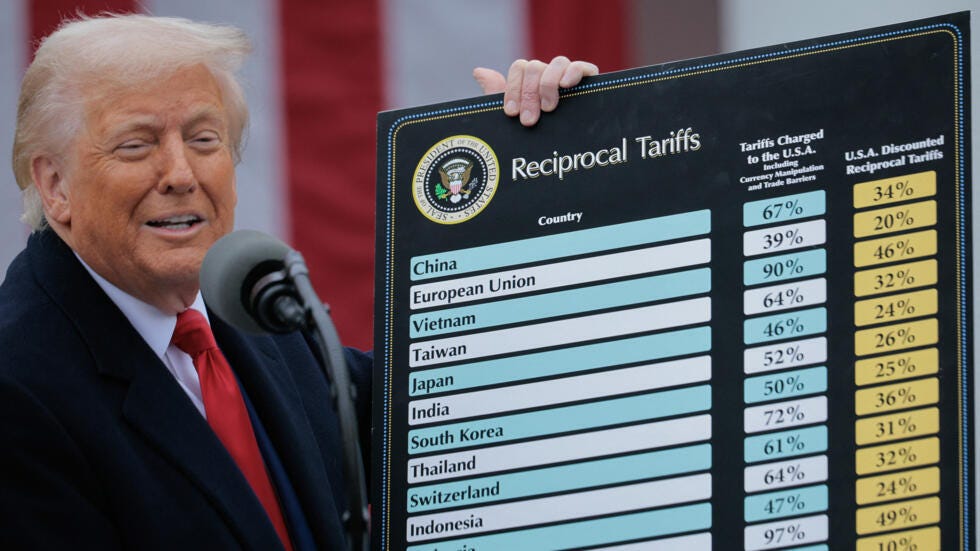

On April 2, 2025, U.S. president Donald Trump finally put his long-baited plan of introducing tariffs into action. In a nonsensically-calculated gamble, his administration introduced sweeping tariffs across the world: 54% for China (far from the previously promised 100% rate), 46% on Vietnam, 24% on Japan, 20% on the European Union, 29% on the Norfolk Island (population 1200; but no additional tariffs on administrative overseer Australia, who retains the 10% baseline along with the UK).

The Trump administration calls these tariffs “reciprocal”, by which they mean that, according to them, the affected countries charge the same tariffs on US imports. This has been found to be untrue (and can very easily be disproven with just a Google search). In actuality, the calculations were even more nonsensical: the White House took the total trade exchange between theirs and the target country, expressed as a percentage and then divided by two. For example, in 2024 the US imported 439.9 billion dollars worth of goods from China, while they only exported $295.4 billion worth to China. This creates a trade deficit for the US (and conversely a trade surplus for China) of ~439-295=$144 billion, for a total trade value of 439+295=$794 billion.

Then, they divided exports by imports, that is 295/439 = 0.67 (times 100 to get 67%). This 67% rate, the White House claims, are tariffs charged for US goods when they enter China, but this is false. Then, this percentage result was divided in half (no reason is given as to why) to get the “discounted” 34% tariff rate the Trump admin is now levying on Chinese goods — for a total of 54% as 20% duties were already charged under previous laws.

The equation has experts scratching their heads because they make no sense on any level, while the White House continues to insist these tariffs are reciprocal. Long-standing US vassal states such as Japan, South Korea and even the EU have tariffs applied where none existed before. Countries that account for very little trade with the US, such as Malawi — who exports only $43 million worth of goods to the US — gets hit by a 17% tariff rate. For the US, the loss of this money is not even a rounding error. For the small African country however, this could mean an impending humanitarian crisis as jobs will be destroyed amid this loss of trade.

The White House has also lied about how tariffs work back in the first Trump presidency. At the time, they claimed that tariffs are paid by the exporting country, let’s say China for the example. When a Chinese company exports something

This is completely wrong too. Tariffs are a protective measure enacted by the importing country. The intended goal of tariffs — and this provides an inkling of a reason as to why they are enacted so broadly — is generally to protect or even restart local production. Tariffs are paid by the importing company. That is to say, if a US company such as Apple manufactures its iPhones in China, they eventually need to come back to the US to be sold to customers there. When this happens and the iPhones make it to US shores, then the tariff is levied: an iPhone costs $440 to manufacture for Apple, and 54% of this value ($237) will be charged to Apple for each iPhone that it imports from Chinese factories. Another important point: the money from the tariff goes straight to the US treasury.

Two problems arise from these tariffs. First, the company will raise the price of its products to the end consumer to offset the cost of the tariffs. A 50% cost increase along the manufactoring chain means in all likelihood a 40-50% increase to the final price. An iPhone already costs $800 in the US, and this would increase the price

The second problem is that these tariffs are broad. Even if Apple wanted to move production somewhere else, they would still have to pay tariffs. That’s also if they can even find a country to take on the volumes they require. A bid was tried in India for a time but is not panning out for Apple as Indian factories can’t output the amount of products Apple sells in time.

And it’s not just Apple. All companies dealing with imports along their production chain (which is to say almost all US companies) will now have to pay these tariffs. Even companies that individually only deal inside the US still likely have suppliers somewhere along the line that rely on imports. In the modern age, no advanced economy such as the United State’s can produce literally everything it needs, including the raw materials.

For example, a company based in the US printing T-shirts in small orders might very well gets its T-shirts, ink and computer software from other States businesses. But the company that sells them the T-shirts probably gets them from Bangladesh (37% tariffs), Vietnam (46%) or China (54%; and yes, China is the biggest exporter of textile worldwide!)

Just like VAT, cost always makes it to the consumer. At a time of impending recession, and when most US locals are living paycheck to paycheck on a minimum wage that has not increased in over 15 years (and barely), this could mean a very real catastrophe. In the end, you will be the one paying for these tariffs.

And it’s not just a problem for the US. Everyone will be impacted by these tariffs — workers are also consumers, and if local businesses lose the US market, it could mean joblessness in the short term (and perhaps long term for more vulnerable countries, i.e. imperialized countries such as Malawi). In the longer term, it will also make things more expensive at home: as much as US products have a bad reputation globally, even EU, Chinese, Indian, Japanese companies rely on them at some point in their supply chain, be it for petroleum or steel.

Businesses — and by extension the state — require consumers to purchase their product to create profit. These tariffs promise to upset stability globally and for consumers worldwide. Although the stability professed by the US is one that relies on the looting of the Global South to maintain high living standards in the US and EU, it is still stability: defined solely by something which stays in the same state.

It then asks broader questions about why exactly tariffs are needed, if the US is already the one leading global trade.

The beginning of an answer can be found in recent (from around the last 10 years) developments globally. It is no secret that the US is at odds with China — well, not just China, but primarily China. Why is that? It’s because China is now the biggest economy on the planet on the global stage, and has been since 2020.

This is a little known fact as GDP is generally calculated in absolute US dollar terms. However, a closer measure of GDP is PPP, or Purchasing Power Parity. This calculation takes into account inflation in individual countries as well as their relative cost of living.

The problem is like this: if the median wage in a country is let’s say $300, then a haircut (or any other good or service) can’t cost $25 like it does in much of the West, because nobody could afford it. Thus a haircut will cost perhaps 1 to 3 dollars adjusted locally. But while a haircut in the US will increase GDP by $25, it will only increase the GDP of that country by $3. Yet the haircut is the same service, and so purely absolute GDP is not a good measure of a country’s production.

GDP is not a great measure of a country’s economy, but it gives some surface indication of how tides are shifting and evolving. As such, no analysis of global events — and I mean truly global, affecting everyone — can be made without putting China in the equation.

In the past few years alone, the US has ramped up attacks against China, propping up riots in Hong Kong in 2019, concocting a fabricated story about a Muslim “cultural” genocide in Xinjiang (while the US was drone bombing these same Muslims in Pakistan throughout the 2010s), later hijacking the COVID-19 narrative to point the blame to China while in the US, over 1 million people died from covid — the most of any country. In 2024, the US passed a bill to fund a 1.6 billion dollar program simply to publish propaganda against the People’s Republic of China and nothing else.

There is a very clear reason for the US to single out China, the growing economy that is responsible for a third of all global manufacturing, and it’s because since the end of WW2 and the Bretton-Woods agreements, the US has been able to come out as the imperial hegemon. Global trade was conducted in US dollars — this did not come about organically, but as a condition of the agreements. This is the petrodollar, which reinforces the strength of the US dollar and forces virtually every country in the world to own a reserve of US dollars. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, who provide predatory loans to countries in the periphery of this hegemon, were also established under this system. With baited loans, they force countries to accept ludicrous interest rates (usually 14%, sometimes up to 21%) that come with strings attached: the money usually goes into highly profitable industries, such as mining or petroleum refining, and must be paid back in 7 years. They usually also require the recipient to pass laws for the benefit of the “free market” (read: the free transit of Western capital with no government barriers). If the country can’t repay (and the loan is calculated so that it can’t), then defaulting clauses force them to sell the entire project to Western companies — see Argentina in 2001, for example.

These two instutions are only part of the global chain of modern imperialism: at prior levels, CIA operations or color revolutions make sure to keep countries teetering on the edge of collapse and ready to accept any sorely-needed funds. This exploited periphery, we generally call the Global South.

But these new tariffs target every country in the world — and even non-countries, with territories like Heard Island (10% tariff) that is inhabited entirely by penguins. So what gives?

Well, some circles have been talking of a New Cold War for several years now. Much like the first Cold War positioned the US against the USSR, the second-biggest economy in its time, a new Cold War is now being waged against China. China provides the antithesis to everything the US does: their loans come with no strings attached (hence why African countries prefer them) and target precious, but unprofitable, infrastructure projects such as rail and road. The US economy has also made a costly choice back in the Bretton-Woods agreements: they bet on becoming a financial center, producing nothing but controlling the flow of physical goods and trade worldwide. This worked very well for a time, aided by CIA operations to depose, install, or completely restructure entire states as needed, but history shows no empire lasts forever.

The tariffs can be seen in this light, especially if we consider just how dependent the US economy is on finance — finance being the business of money itself. It is a very dire prospect for US businesses, who have been relying not on production (see Detroit and the rust belt) but on the control and flow of trade: importing and exporting products, often only serving as the middleman in a long chain. What is produced for the benefit of US companies is usually produced… in China, hence the 31% global manufacturing share.

The clock is ticking for the US model. The economy is slowly sinking as the global financial system they installed is breaking down. With coalitions like BRICS, which are now moving towards trading for petroleum in their own currencies (China itself conducts more than half of its transactions in its currency, the Yuan, from just 20% in 2010). African countries are also taking Chinese loans over IMF loans as they are more favorable, and with China being able to produce so many goods so efficiently, they are also building up resiliency: as an example, consider that Lockheed Martin announced the delivery of the 800th THAAD missile (of all time) in December 2023. Production began in 2007, which means only 50 missiles per year can be delivered. For comparison, China fired 250 ballistic missiles in 2019 in one exercise.

In other words, the US is increasingly becoming isolated from the system it set up, and this is very scary for Washington — for both Democrats and Republicans. For a long time, the New Cold War circles have been fearing an open war against China in a last-ditch effort for the US to try and contain the Asian superpower. It seems however that even the Trump administration realizes just how bad of an idea this would be (especially now that China has means to take out the once-feared Aircraft carrier undetected, and the US knows this: they consistently lose all wargames simulated against China).

The tariffs can then be seen as one of the last-ditch attempts to reshore production to the US, which is something businesses don’t particularly want to do. It is cheaper to produce in China and elsewhere, sometimes due to labor costs or, in the case of China, simply from economics of scale and manufacturing efficiency (famously, factories now have trouble finding workers in China and have to offer higher and higher incentives). These tariffs aim to force businesses to relocate production to the United States in any way possible, but there is certainly a contradiction: if the writing is on the wall for the US economic model, why do businesses not reshore willingly while they still can?

The reason is that the point of a business — and indeed how a capitalist thinks — is to make as much money in as little time as possible. An investment into reshoring would be substantial for any business, potentially in the billions. This cost is not helped by the fact that production costs are simply higher in the US, and a textile producer in Alabama could simply not offer t-shirts at a $10 price tag or even $30, for higher-end budget options.

In a way, the tariffs indicate a shift towards a manufacturing economy like the US still had until the 1970s, perhaps also accepting that the Bretton-Woods order is coming to an end, or, at least, will be significantly diminished. It is very likely that the Trump administration also feels like they can successfully conduct this reshoring with the help of the tech industry, for example using AI to bridge the gap with the inevitable labor shortages (whether that will even work is another thing entirely, considering that the White House got its tariffs calculations from a chatGPT query). Opening a factory in a location is not the only challenge — one also needs talent to set up the factory and work in it. This is a problem that has been known for years already, and perhaps it indicates why businesses have been so cold towards reshoring, and why their hand might need to be forced if capitalism in the US is to continue at all: we simply don’t know how to produce some things anymore in the West, everyone has forgotten how. For example, up until just January of this year, MP Materials had their rare earth materials processed in China. They are now reshoring processing, but whether that bid will pay out is another thing.

We should probably expect more aggressive actions from the US beyond these tariffs. These might just be the second or third step of the long process of salvaging US capitalism and its quest for the mighty dollar — with the first steps being taken under the first Trump presidency (the Biden presidency did not achieve anything of note, perhaps best announced by Biden’s own slogan: “Nothing will fundamentally change”).

Is war entirely out of the picture, though? Maybe not yet. This will depend on if the economic incentives and disincentives will be enough for the US government to get itself to where it wants to be. As mentioned, it is entirely possible that they will be content to accept a diminished role not as the global hegemon but as a power in a multipolar world. Barring a coup, the Trump presidency will only last 3 more years after all. Only time will tell for sure.

In the meantime, everyone should expect price increases and make sure to look at their local news and conditions to see how the situation evolves for them, because this will have global repercussions.