1692: The Salem Land Dispute Trials

Witchcraft actually gains even more luster when the real cause is accounted for.

If you like this article, please don’t hesitate to click like♡ and restack⟳ ! It’s a quick way to make sure more people will get to enjoy it too.

And don’t hesitate to subscribe to my newsletter for free to receive my new articles right in your inbox!

In January 1692, nine-year-old Betty Parris, daughter of Salem’s Puritan minister, fell ill. The New Years’ had just been celebrated in the colony, and as the dead of winter settled in, an ominous disease would start to ravage the small village of five hundred. The child exhibited strange symptoms: she would lose herself in fits of convulsions, speaking unintelligible words. At times, she would bark like a dog or throw things across the room.

Betty was not the only victim to this strange illness. Other girls quickly came under the influence of the spell as well. Reverend Deodat Lawson made his way to Salem Village to see the illness for himself and offer words of advice to his parishioners. He rode his horse in the dead of the night to the Village, arriving at the inn under an auspicious moonless sky. Wasting no time, he asked the innmaster to bring him one of the afflicted for himself. Under a flickering candlelight, he observed teeth marks on 17-year-old Mary Walcott’s arm, for which there was no explanation. Later that evening, as the Reverend met with the Parrisses to discuss these strange happenings, 11-year-old Abigail Williams burst into the room, crying out “Whish! Whish! Whish!” before seizing logs from the fireplace and throwing them about the room.

Thus began the Salem Witch Trials, lasting for almost a year. All in all, 19 people — a majority of women, but some men as well — were tortured, tried and hanged for their crime of witchcraft against upstanding and moral Puritan girls. Hundreds overall were accused.

It makes for a great story, doesn’t it? The Salem Witch Trials have all the components of a scary urban legend: young girls afflicted by an unexplained disease. Older women performing witchcraft with the devil. A small, remote Puritan community prey to powers they do not entirely understand. The fear of the unknown, and the place of God and religion in a superstitious, patriarchal society.

In fact, it’s such a once-in-forever story that even more serious accounts of the trials start with the gritty and creepy aspects, feeding into our morbid fascination of true crime stories and how people could do so much harm to so many innocents for so long based on a faulty premise.

Nowadays, the cause of the trials is usually attributed to the “fear of the unknown,” understanding that people back then thought they were truly dealing with witchcraft, but that we know better in the 21st century.

The Salem Witch Trials thus exist in a contradiction in its modern version: on the one hand, people of the past were superstitious and didn’t understand what they were dealing with. But on the other, we must ourselves heed the warning of the trials, and not fall into the same superstitious dead-ends.

Thus the events are not simply a historical event anymore; they’ve taken a life of their own, becoming a story with a moral and a point to drive home.

But still, what explains the story, then? The events are one thing, but what about the cause — how did two girls fall ill, and why did the trials last for almost the entirety of the year of 1692?

Suddenly, the narrative crowd doesn’t have much to offer. Some historians try to handwave the trials away with far-fetched explanations such as ergot poisoning, a favorite of the ‘mass hysteria’ — for one, ergot poisoning wouldn’t explain why only some people were afflicted by the symptoms or why the Massachusetts legislature let the trials go on for so long without intervening. The role of religion is also a favorite explanation: God-fearing men and women dealing with the devil is a great timeless story sure to make a best-seller.

But there is a well-preserved and highly detailed historical record of the trials and the people involved in Salem Village. We tend to think of the past, especially before the 19th century, as a time of chaos, lawlessness, and ruling superstition; but the village of Salem and its nearby town had highly-developed laws, public administration and courts of justice. They knew exactly who owned what, how much of it, and where land plots started and ended. In fact, the Salem Village was oftentimes at odds with the nearby Salem Town, which for most of its history directly governed over the village.

When carefully examining this historical record and not looking solely at the Trials themselves but at the entire context surrounding the colony of Salem Village, we come to a much deeper understanding of the events of 1692: the trials were about land disputes. A very material and worldly problem.

In doing so, we peel away the superstitious layer of the story, and at the same time remove its narrative that turns this very real historical event into a story to gawk and shake our heads at, and placing it back right-side up where it belongs: as a historical event that can be analyzed like any other, with the proper tools and methods.

Law in colonial Britain

We must first understand that witch trials were not entirely uncommon in the British colonies. However, what separates the Salem trials from others in the colonies was the length and scale of it. Usually, a witchcraft accusation would be made in isolation. An investigation would be opened and, if it had merit, the accused would stand trial and that would be the end of it. Not all witchcraft trials ended in convictions.

The Salem trials, as hinted to earlier, lasted from January 1692 (the moment the first symptoms appeared) to the fall of the same year, when the special commission was dissolved. Originally, the accusations did subside for a while. The purported witches — a Native woman named Tituba, widow and elder Sarah Osborne and beggar Sarah Goode — were tried and convicted to death in March, and the matter was considered closed.

Because witchcraft was considered a crime, procedures were in place to deal with it within the legal framework. At the time, this was a completely normal accusation to make in the same vein as robbery, fraud or murder. Thus, when being accused of witchcraft, a formal investigation would open. Men of the Church might have participated in it, not because of the nature of the crime (being in league with the devil) but simply because there was no such thing as the separation of Church and State back then.

Likewise, the use of torture was seen as a normal part of an investigation, and not just in the colonies or even in Britain. When material evidence was lacking, a confession was sought out and torture was a way of obtaining one. The pressing of stones, for example, was enacted to make someone enter a plea of either guilty or not guilty. If the accused refused to enter a plea, then a trial could not proceed.

We must be clear that the trials did not happen through vigilante justice, a mass of villagers wielding pitchforks and torches dragging out “witches” and “wizards” (the male equivalent) out of their homes in the dead of night. The trials and convictions were rendered by judges, who listened to evidence and followed the laws as prescribed. In each case, those accused were arrested at their home, encouraged to confess while the investigation was conducted, and held in jail until their trial.

In fact, one of the most ‘reasonable’ voices in the Court of Oyer and Terminer — the special court that had been set up in Salem Village to oversee the Witch Trials due to the growing number of accused — was Increase Mather (yes, his name was Increase). As part of the court, he urged for the proper following of law. But he had no problem with the nature of the evidence that was brought up or the use of torture to obtain confessions; what he had a problem with was following the proper procedure of gathering evidence in cases of witchcraft, such as following the prescribed methods of obtaining a confession. While a lawful category of evidence was indeed supernatural — for example witnessing a supernatural event — we must understand that all of this was considered empirical and reasonable back in the colonial law system. With no forensic or recording tools at their disposal to determine guilt or the chain of events, authorities had to rely on more crude means of determining the chain of events and guilt.

One lawful and strong category of evidence was the witnessing of supernatural feats. In May 1692, six persons testified in court that George Burroughs had lifted a heavy gun at arm’s length with a single finger thrust into the barrel. This was considered sufficient evidence, and he was hanged in August of that year.

We can now divorce the historical events from its more grandiose retellings: nothing that transpired during 1692 was out of the ordinary as far as procedures were concerned. There didn’t even seem to be fear surrounding the events of witchcraft that befell the village. Going by the historical record, everything was handled as per procedure, as one would investigate a robbery or other crime. What was out of the ordinary was the amount of accusations, certainly, but not the manner in which the trials were conducted or how the law was applied. In fact, out of the more than 200 people accused of witchcraft by Salem villagers, “only” 20 were convicted and executed.

Village and town

To further make sense of this chain of events, it’s important to understand the geographical situation Salem Village found itself in.

The Massachusetts Bay was settled earlier that century, in 1626 specifically, because of its attractive economic opportunities. The bay formed a natural harbor with plenty of fishing opportunities. Salem Town was founded and quickly grew to become a prosperous colonial settlement — one of the richest in the colonies, in fact.

Salem Village, where the trials took place, was located slightly up northwest of the Town. When settlers arrived at what was then called Naumkeag (fishing place) by the Massachusett tribe, they found empty but sturdy buildings and moved in to appropriate them. The Naumkeag were partially nomadic, and had moved up north for the summer. These buildings were not abandoned, but simply unoccupied for the season.

After stealing these homes, settlers swiftly set out to remodel them to their European tastes. Upon returning to Naumkeag in the winter and discovering that people had occupied their homes, the Naumkeag welcomed them as people in need of help, and proceeded to help teach the Puritans how to grow corn and survive in this land.

Over the next few years, the town of Salem quickly grew, and the village arose to bring some of those European systems and methods to the land they had invaded — more specifically, the village mainly served as the food source for the bustling town.

With this growth, the village asked in the next decade permission from the town to expand their settlement to the west. They needed not only to house all these new settlers, but also to find more fertile land to grow crops in the European manner. Few of the grantees at the time actually settled the land themselves. Instead, they sold their grant to families who established themselves on this Native land: the Princes, Putnams, Swinnertons, Porters, Hutchinsons or Ingersolls — all names that will appear over and over again in the Witch Trials half a century later.

At the time, Salem Village didn’t even exist as a place. It was known as Salem farms and was considered part of the township. In return, the farms paid taxes and provided some labor to the town. They were completely dependent on what the town decided, which included land ownership — or in other words, the nearby Salem Town was responsible for the transfer and purchase of land in the Village.

For most of its history up to 1692, Salem Village found itself in a muddy status in regard to the nearby town. They were vying for more autonomy, like other settlements in the area had been granted, because the village wanted to take care of its own issues. For example, they disliked having to serve in the night watch (in rotation), as the town was located quite far away from the village. They also argued that they provided food for the town but received very little in return; it was only in the 1672 that Salem Village was allowed to have its own place of worship and bring in its own minister, James Bayley, who had graduated from Harvard only three years earlier.

We must understand at this point that Salem Village was not some remote, desolate place where harsh conditions prevailed leading people to find solace in religion and superstition. Massachusetts was one of the wealthier colonies at this time and a very successful port which welcomed thousands of settlers, all built on the back of the Indigenous population that welcomed and taught them how to survive even as they were being displaced from their ancestral homes by these newcomers. Trade abounded, and every week ships bound from and to Europe travelled through the Bay’s ports. This trade, of course, also included enslaved people from Africa in destination to the European colonies.

A picture starts to emerge: the villagers in Salem were not some backwoods know-nothings who had barely discovered the pointy end of the pitchfork. They understood the law, they understood how they were governed, they earned money for their work, and they had disputes over their conflicting interests. Some families in the village in fact — including the legacy families that had been granted the original charters of land — were quite wealthy landowners. But still, the village only existed to feed the Town on the cheap.

Throughout the 60s (the 1660s, that is), the village had petitioned to be released from the night watch obligation, on the basis that they lived some ten miles away from it (which translated to several hours walking to and back). It got to the point where the General Court in Boston got involved, ultimately releasing any farmer living more than 4 miles from the meeting house from this obligation.

But not everyone in the Village found the Town to be overbearing. All this time, we’ve gone through the reasons the town might have wanted the village to remain in their administrative grip and the reasons the village might have wanted to break away from the Town, but we haven’t really asked why they had these interests.

The answer that becomes increasingly clear from peering over the historical documents is that it was about land distribution.

There was certainly plenty of land to steal from the Indigenous nations in the New World. But it was not stolen as one pleased. In the colonial system, authorizations were necessary — again, the system of law was well-developed and established even so far away from London. Any land owned by the village would be land prevented to the town, limiting its potential growth. And, any land that the wealthy landowning families in Salem Village coveted would require authorizations to be granted to them. Land is a source of wealth, and has been a major driver of class conflict throughout history (the other being labor and who gets to own it). By owning more land, these families ultimately owned more wealth for themselves.

Some very interesting data exists to support this deep-rooted underlying struggle. By the 1690s, the third generations of farmers was starting to emerge in Salem Village. Of course, inherited holdings were divided equally amongst the sons. This means that by the time of the third generation of sons, what started as one large plot of land to grow crops on (which were then traded through Salem Town by merchants to be sent to other colonies) could have been divided into 9 or even more parcels. Subtract the portion the farmer needs to grow his subsistence, and there’s not much left to trade with the town. Moreover, topographical data shows that the most fertile land in the village were on the east side, near the bay. The western side, which had been settled later, featured marshy and hilly terrain less suited for agriculture.

Likewise, the eastern side was closer to the roads and waterways that led to town and as such had an interest in remaining somewhat embedded with the town to continue receiving these benefits, as well as trading their crops with the town.

Is it any wonder then that when the trials came to be, most of the defendants lived on the eastern side?

When Samuel Parris discovered the affliction in his nine-year-old daughter in 1692, he was embroiled in devices of his own within the village. Parris had been hired as the Village’s minister only three years earlier, for an annual salary of 66£ on top of the church taxes he was allowed to collect from the villagers (though whether they decided to pay those was another matter).

Two weeks after Parris’ hiring, the village chose two selectmen, allowing them to petition just the next month, in August, the Town selectmen for a total separation of Town and Village, establishing the Village as an independent township — though this attempt ultimately failed.

In October, another general meeting at Salem Village voted to give Samuel Parris and his heirs the Village parsonage together with its barn and two acres of land. This was very unusual, especially as the Villagers had agreed in 1981 that they would never give away the parsonage (a church house provided by the village and belonging to it).

Interestingly, the men chosen to carry out the transaction for Parris were an Ingersoll and two Putnams — two of the established families that bought land grants west of Salem Farms for settlement in the 1630s, the more marshy and hilly area that was less suited for agriculture and further away from town.

The conclusion certainly seems to be that independence was to be reached through the formation of a Church, especially due to the way Puritanism worked, with no central church authority. If Salem Village was allowed to establish its own Church, then they would have very weighty arguments for independence from Salem Town, becoming its own township.

And if pro-autonomy villagers could ensure that Parris remained as minister (after going through a series of ministers in a few short years), then they would more easily be able to petition for autonomy. These became known as the pro-Parris faction, led by the Putnams.

On the other side was the anti-Parris faction, led by the Porters. The Porter family, notably, owned a sawmill (highlighted in red) on Ipswich road which delimited Salem Town from Salem Village. Ipswich road was located at the far east of Salem village.

The Salem Land Dispute Trials

The Putnam and Porter families were the two wealthiest families in Salem Village. It was very fortunate then that one morning of January 1692, Parris’ own daughter would fall ill to witchcraft.

Samuel Parris of course had interests in following along with these machinations, even if he was sort of a pawn at the center of it. What was important was not Parris himself necessarily, but the establishment of a church in Salem Village. However, if his faction came out victorious then he was essentially assured that he would remain minister for life in Salem. And certainly, if the relinquishing of the parsonage unto him was any indication of things to come, he had a very bright future ahead of him.

Parris’ role was not solely to start the trials. As a member of the Church — and Salem’s own minister no less — he served as a witness in trials and used his sermons to rouse up animosity towards the anti-Parris faction.

It becomes very interesting then to see who were accusers and accused in the land frenzy. While over 200 people were accused of witchcraft (with several of them residing not in Salem Village but in the Town), some interesting data emerges when looking at their background.

Originally, three accusations were made against outcasts and ‘deviants’ in the village: a Native enslaved woman, a destitute beggar, and a bedridden grandmother. The three were arrested and two of them tried and executed (Titube, the Native woman, died in prison years later) and the accusations died down for a while. In March however, they picked back up with the following prominent characters:

Several men with “great estates in Boston”;

a wealthy Boston merchant, Hezekiah Usher, and the widow of an even wealthier one, Jacob Sheafe;

a future representative to the General Court;

the wife of the Reverend John Hale of Beverly (a man who had himself supported the trials);

Captain John Alden, one of the best-known men in New England (and son of the now legendary John and Priscilla of Plymouth Colony);

the two sons of a distinguished old former governor, Simon Bradstreet, who were themselves active in provincial government;

Nathaniel Saltonstall, a member of the Governor’s Council and for a time one of the judges of the witchcraft court;

and Lady Phips herself, wife of the governor.(Source: Salem Possessed, Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, 1974.)

Many of these accusations never even made it to trial as evidence was judged too little to proceed. Additionally, many of the charges were brought by the Putnam and Ingersoll families. Notably, Ann Putnam Jr, daughter of Thomas Putnam, was a prolific accuser at the time, though only 12 years old. In 1706, she made a confession to Parris’ successor in Salem Village that she had been manipulated by her father to make the accusations of witchcraft.

Parris himself remained as minister in Salem Village until 1697. At which time, a general meeting was assembled and essentially reversed all he had acquired: the parsonage was transferred back to the village, and he was dismissed from his functions. He left Salem and found employment as a minister in other colonial towns. Ultimately, the Putnam family failed in their plot. The Court of Oyer and Terminer was disbanded by the governor of colonial Massachusetts and the matter seemingly closed. Though some years later, an inquiry was reopened to review the cases and compensation paid to the family of the victims, most of whom were exonerated. Today, Salem Village is the township of Danvers in occupied Massachusett land.

The Pro-Parris faction had lost.

Why is any of this important?

Putting all of this together — the legal framework existing at the time, the disputes with the town and the two factions, the landowning families — we must inevitably come to the conclusion that the witch trials, though widespread in Salem Village, were nothing more than families solving their land and property disputes within the legal framework existing at the time.

This explanation demystifies the lore surrounding the trials, and as much as the stories of witches and supernatural powers might be interesting come Halloween, it is a good thing to demystify the world. The actual witchcraft theory is of course not believed nowadays — and it may not have been believed back then by the accusers either, who knew very well that they were using legal mechanisms to achieve their goals.

Mysticism is the belief that there are things in the world humans will fundamentally never be able to understand, no matter how hard they may try. To demystify is to assign a clear cause and reason to change. It is the belief that, as writer Maxim Gorky embodied in his works, nothing human is alien to me.

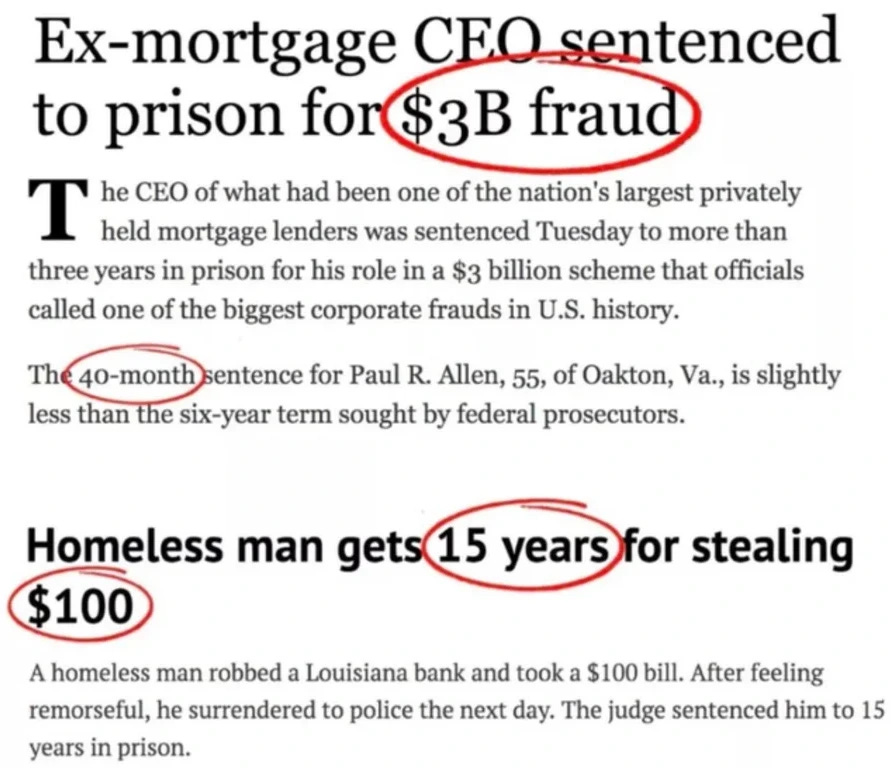

There was no witchcraft, but there was a legal framework for forcing people to surrender their property. These loopholes still exist today: law and legislation lags behind the needs of society, and likewise witchcraft laws were still on the books and taken seriously insofar as they represented a legal case brought up by respected (wealthy) families to the governing authority. Today, we are lagging behind in terms of legislating AI. We continue to have homelessness by refusing to build homes due to existing zoning laws — these mechanisms are used to keep people in poverty and others in power. Britney Spears was put under tutelage for over a decade, putting her fortune under her father’s name so that he could have access to it. This is not witchcraft, but civil forfeiture that still happens to this day.

All of this didn’t come about by mistake or happenstance; it was deliberately created at some point by someone with a name — and the power to legislate. The Putnam and Ingersoll families of Salem still exist and they still live there. The weight of the past bears on the present, preventing us from doing as we please.

People in Salem were not taken by a temporary panic, ergot poisoning or a sudden outburst of religious zeal — all causes that remove agency from the accusers and contributes to mystifying the trials as something that somehow exists outside of the realities of society. I’m not sure how the Puritans are portrayed in U.S. history classes but in the rest of the world, we tend to see them as backwards, deeply superstitious people confused by any sort of technology invented after the Middle Ages. Almost 150 years after the trials, Alexis de Tocqueville praised their democratic and egalitarian ways, their emphasis on education, their knowledge of law (after their repression in England), and their innovations in governance. These Protestants were, after all, expelled from England as they threatened the privileges of the king as head of the Church — when the king had just been reinstated after the Cromwell Rebellion which saw Puritan Oliver Cromwell execute the king of Britain in 1649, placing himself at the head of a non-feudal, non-monarchical Britain. Cromwell would be executed in 1658 in a counter-revolution and the Puritans deported to the colonies to destroy their power.

We live in the real world and accordingly need real solutions: laws and governance, land distribution and division of labor, etc. All of this matters because we can only study the world correctly (that is, come to the correct conclusions) with the right tools and frameworks. The follow-up question is that if we can study the past with the right tools, then surely we can also study the present and even the future — and maybe even with the same tools. Through this study of the Salem trials, we understand that people in 1692 were not so different from us: they had the same brain structure, the same limbs and the same genetic makeup we do. They lived under laws and state institutions that ruled their lives constantly, just like we do.

We can’t undo the witch trials. But we can learn to use the tools that we possess right now to understand the world, and analyze why the societies we live in today are the way they are: why the United States is forever at war, why ISIS has made a resurgence and seemingly can’t be defeated, why we still have homelessness and job insecurity despite companies announcing record profits. The world can be explained and demystified, but only with the proper tools. And after that, it can be changed.

Your support helps me keep writing these in-depth essays. If you appreciate my work, consider joining the Critical Stack and gain access to our private Discord community!

Bitcoin (BTC SegWit network) - bc1qcdla40c3ptyrejvx0lvrenszy3kqsvq9e2yryh

Ethereum (Ethereum network) - 0xd982B96B4Ff31917d72E399460904e6F8a42f812

Litecoin (Litecoin network) - LPvx9z9JEcDvu5XLHnWreYp1En6ueuWxca

Upgrade your subscription here:

Share this essay:

This is a great article because it follows the money behind the Salem Witch Trials, and following the money is the best way to discover the truth.

I'm working on a post about King Philip's War, which preceded the events you talk about by 17 years. You might be interested in the video, and I would certainly be interested in any thoughts you have about it. It's not too many people who delve into this part of our history.

Wow, sounds like Salem was an old school offensive mkpsyop using old school lsd. A precursor to mkultra. Thanks for this insightful study. I would very much appreciate your read on this related subject matter @ https://open.substack.com/pub/treeborne/p/we-are-in-the-last-stretch-around?r=5nefo&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true. Regards and well wishes.